JUST AROUND THE CORNER

| February 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 1

“Modernism’s transposition of perception from life to formal values is complete,” wrote Brian O’Doherty of the modern gallery space. In his seminal 1976 treatise, Inside the White Cube, O’Doherty argued that the context in which art was shown had become irrevocably conflated with the art object’s own content, a Gesaumtkunstwerklike sublimation of subject and object, art and life into aesthetic feats so finite and complete as to inhabit death: “This, of course, is one of modernism’s fatal diseases.”

In 2008, three artists (Rania Ho, Wang Wei, Wei Weng) and one curator (Pauline Yao) founded Arrow Factory, a self-described “alternative storefront art space” aiming to reinsert the contemporary art exhibition into the fabric of daily urban life inside Beijing’s Second Ring Road. Disavowing the elitism and the artifice of the commercial gallery system and its disconnect with the immediate surroundings (like the galleries of Caochangdi, fortified against the village at the door with gates and grey brick walls), Arrow Factory is located away from any of Beijing’s identifiable art communities down a quiet hutong in the center of the city. Where the white cube would negate or exclude any context interfering with the perception of its showcase of Art, the former vegetable stall’s fifteen square meters of space seek to embrace it, “[bringing] artistic participation, exploration, and experimentation up against the social and political realities of everyday life.”

With such explicitly stated motivations, the space seems to beg for its own critical evaluation. So: more than a year after its unveiling and with seven exhibitions behind it, are the practices embodied by Arrow Factory an antidote to the ills of Beijing’s art community? What have been the real effects of inserting contemporary art in the midst of a local community that, of its own admission (like the neighbors who tell its founders that they’d be better off selling vegetables), takes little interest in artistic affairs?

“Just Around the Corner,” the Factory’s fall group show of fourteen artists, is the space’s most significant attempt to answer these questions. The show was broken up into four groupings of artists and works, each lasting approximately one month. The works ran the gamut, from simple gestures like Lim Tzay-Chuen’s donation of a jar of Nutella to the bakery next door to Koki Tanaka’s hutong performances and their attendant video works.

Each work in the exhibition was conceived as a direct response to the physical, social, and ideological location of Arrow Factory, resulting in a collection of prosaic interventions that imposed the praxes of the contemporary arts on the surrounding community without inviting its authorship. Instead, the ideologies that fuel the works are self-perpetuating: like the title of Wang Gongxin’s spring exhibition at Arrow Factory, “It’s not about the neighbors” but still eminently concerned with them. Such works are participatory in the sense that they ask permission of their subjects: Lim Tzay-Chuen and his Nutella; Liang Yuanwei convincing the local garbage collector to add the new cans she placed along the hutong to his daily pick-up; the Xijing Men displaying their video works on TVs planted elsewhere on the same alley; Hong Hao distributing unwanted art publications through a neighboring produce stand.

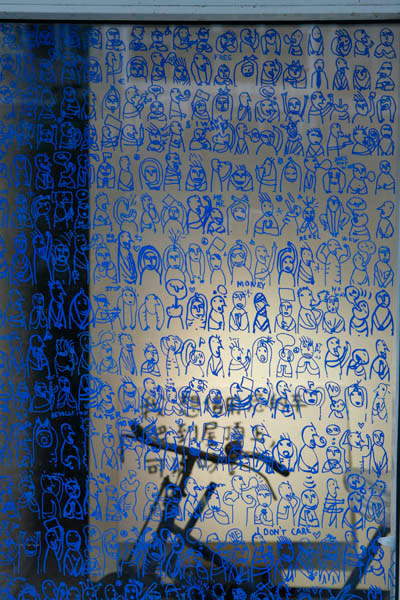

Other works prefer to hide in the crypt behind the space’s glass doors, embalming art and ideas about art in a complete separation of object and viewer that the white cube can only aspire to: Koki Tanaka’s video works Rooftop Walking and Going Up and Step Down (both 2009); Ken Lum’s Coming Soon photo display (2009); Wang Wei’s I Won’t Make Any Trouble For You (2009). Art lies inside the glass doors; life walks by and peers in at it.

Yan Lei’s Locals Only (2009) stands as an exception: After installing an air conditioner inside Arrow Factory, the artist then passed the keys onto a local resident, Mr. Zhao, who hosted events of his own desire in the small space. Although the work remains authored by Yan Lei, its design allowed for a collaborative negotiation of the possible (and different) meanings of the space to the local community. Similarly, even as it remained behind glass doors, Wang Wei’s I Won’t Make Any Trouble for You visualized Arrow Factory’s possible local positions by displaying his imagined responses to questions the police might ask him over his stewardship of the space.

In the aftermath of contemporary Chinese art’s international ascendancy, this is art that has gone guerilla, fighting for its relevance on the ground now that its birthright has been secured on the world stage. Spaces like Arrow Factory (and other new “alternative” spaces like Elaine Ho’s HomeShop and Vitamin Creative Space’s the Shop) represent a significant slippage, perhaps even reversal in modernism’s transposition of perception from life to formal values. But the insertion of contemporary art into the fabric of daily life has occurred according to a framework of relational gestures that valorizes the artist as it immolates its subject. So long as the contemporary art institution preserves artists as the independent authors of their works, O’Doherty’s “fatal disease” will remain uncured. Until then, the elitism of the art institution has been challenged by moralities of the vernacular. Angie Baecker