CENTRAL ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS 60 YEARS OF DRAWING

| April 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 2

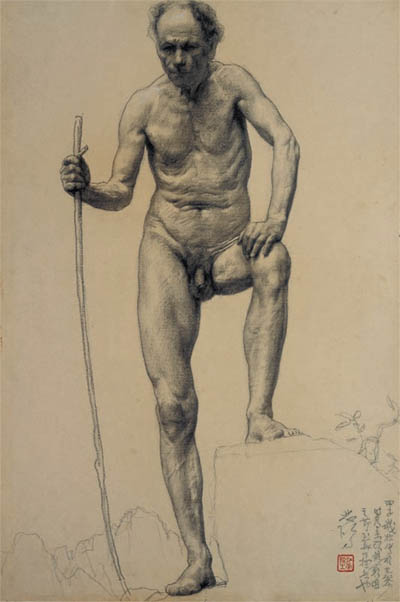

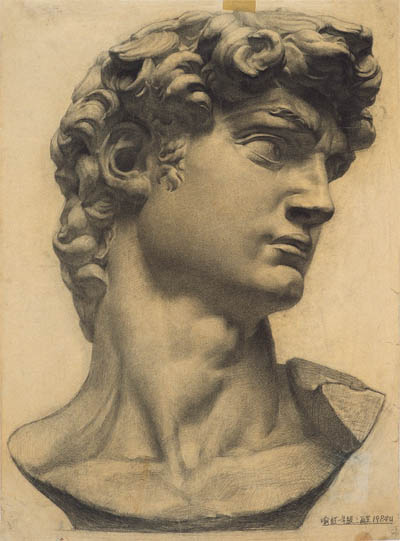

Perhaps only in China does an established artist remain famous long into her career for a sketch made as a firstyear class assignment: Yu Hong’s “miraculous” drawing of a plaster bust of David has become a legend passed down by generations of art students. Younger artists know the sketch from the many textbooks in which it has been reprinted; many can still clearly remember their excitement upon viewing Yu’s homework assignment for the first time, thinking, “That David is alive!” Small wonder that a poster featuring this work hangs conspicuously in the entrance hall of the show “Central Academy of Fine Arts 60 Years of Drawing.” But when visitors re-encounter the original, they will discover a large tear in the upper left-hand corner, inching toward the drawing itself. The drawing, entrusted by the artist to Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), has clearly not been taken very good care of in the depository despite its leading status in Chinese art pedagogy. This exhibition understands itself to be righting the wrong represented by Yu’s damaged piece, affirming the importance of drawing to the entire art-school enterprise. Yet interestingly enough, this process of affirmation is also a rhetorical process of defining the value of drawing for a changing educational system, a process in which Xu Bing plays the leading role.

“Central Academy of Fine Arts 60 Years of Drawing” is the first major project Xu Bing has organized since returning from New York to take the post of deputy director at CAFA. From the amount of work that has gone into the show, it is obvious that Xu (not without CAFA’s energetic support of course) has placed much importance on his role as curator. The show is divided into three sections: “introductory drawing instruction,” “drawing and creative thought” and “individual case studies.” The immense amount of artwork spreads from the second floor exhibition hall all the way to the top, the spaces between each piece crammed with explanatory texts, publications and video interviews with CAFA professors. The time span of the pieces exceeds the show’s titular sixty years to include the pre-1949 sketch work of CAFA’s “founding fathers” (Xu Beihong, Dong Xiwen, Wu Zuoren and others). Make no mistake: This is not simply a straightforward documentary exhibition of drawings, but a wholehearted attempt to articulate the central importance of drawing in order to defend CAFA’s orthodox pedagogical tradition and protect the emotional links—particularly those between teacher and student—on which the CAFA system thrives. Although the show has received warm reviews since its opening, it is hard to know how many of these were born of nostalgia for bygone college days.

One point is clear, which Xu Bing explicitly raises in his introduction to the show: drawing, as an art form, was introduced by the West. Xu then moves on to discuss how drawing evolved in China and how it has functioned in art education and practice, but he has no desire to promote a political or even an emotional discussion of the genre. Throughout the show there is a clear attempt to neutralize questions of technique, to turn experimental gestures into internal academic discussions without having to worry about the practical pressures of ideology. From a historical perspective, this is passing judgment in hindsight, since the reason drawing was accepted into China in the first place was that, at the time, it was seen as representative of so-called “modern” culture and closely associated with notions of freedom, democracy, science and even national salvation. While from a contemporary art perspective such a take looks childish, even absurd, at the time every young artist who studied abroad embraced these cultural ideals. Evading discussion of the intellectual environment of the time in talking about drawing and instead acting as if it dropped from the sky into China’s art education system is a very difficult task. Seen in this way, Xu’s introductory text is more of a practical appeal, both tactical and conciliatory.

In the end, the exhibition still has to cope with history, and the artworks reveal more information to us when in comparison with each other. Most evident after viewing the show is that the proportion of images of workers, peasants, soldiers and ethnic minorities in sketch studies has declined over time, replaced with an increasing number of images of people from daily life, their expressions more natural than before and their poses more relaxed. Corresponding to this shift is a diversification and adaptation within drawing pedagogy, as instructors put forward various teaching experiments directed toward “holistic drawing education.” Interestingly, Xu Bing was a representative of this kind of approach in his earlier years teaching at CAFA, and these shifts in vision occurred following reform and opening. Changes in the sort of drawing espoused in Chinese art education have never pleaded innocent from the forces of the political environment and ideology.

Another issue is more obscured in the show—the relationship between drawing and artistic creation. Looking at the exhibition’s structure, the second and third parts both consider this question of drawing as art, yet fail to match the first part in either energy or ambition; this is immediately apparent from the fact that the artworks and artists chosen as examples all evade a certain immediacy. Just as we cannot escape the artistic and historical value of these artworks and the rigorous creative approaches they reflect, we also have to face the question: if the role of drawing is only expressed within the confines of topical art against a grand political backdrop, does this imply that there is no close, directly causal relationship between drawing and “contemporary art”? Following this, another question arises—what is the purpose of art schools? To create model “experts” to pass on a set of established aesthetic tastes? Or to actively foster visual workers with independent spirits and the ability to think for themselves? On this point the show does not provide a clear answer.

Perhaps we can understand the question of drawing as revealing a paradox in our understanding of “technique.” In China’s art education system, drawing has never been looked down upon; rather it forms a fundamental part of the undergraduate curriculum and the main examination subject for students looking to enter art school. Training in drawing is a long-term process that starts long before art school. Therefore, the dogmas and biases of drawing instruction should be objects of concern and introspection on the part of the entire art education system; otherwise the shortcomings of contemporary art education raised by Xu Bing in the introduction are merely pretensions of good manners directed towards western viewers. Sun Dongdong