YOUTH IN COMBUSTION

| April 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 2

The Department of New Media Art at the China Academy of Art (CAA) in Hangzhou has been very active since its inception, and the fifty artists participating in “Youth in Combustion” were mostly its current students or graduates. There was no information about curatorial concept in the show’s notices or introduction, but show announcements online described youth as a “near-peak energy,” possessing uncertainty, possibility and eccentricity. Such declarations are often spoken but seldom realized, and this one created a self-negating paradox: a theme calling for uncertainty quickly becomes no theme at all.

Since its beginnings, Hangzhou’s Small Productions group has easily attracted attention through its collective form and momentum. However, compared with Small Productions’ beginnings, when it was indeed small but also unpolished, compelling and energetic, this show laid bare a creative bottleneck that the group has not been able to break through as it ages: What is the next step after mobilizing people and building a basic structure? One possible reason Small Productions suffers from this problem is its lack of any theory or methodology, which in turn has to do with the teaching style at CAA’s new media department. In addition to offering instruction in technical areas like interactive media, animation and sound, the department has from the start consistently hired well-known artists as professors. And yet on the whole, it seems that all the teaching concept advocates for is a drifting individualism. By going to class, sitting for lectures, paging through catalogues and viewing exhibitions, students acquaint themselves with the work of various artists and then embark on their own work from exploration to imitation— the same sort of self-starting that emerged by necessity from the academy in its earlier years.

Of course, unbound by any theme, the show was rich and energetic. Parody and nonsense humor abounded, from the show’s title (taken from an ill-considered advertisement on Hangzhou buses touting “Princeling’s Puffed Wheat Crackers, Youth in Combustion”), to the dazzlingly trendy array of works on display such as one by the Shuangfei group in which a television was placed screen up in a wheelbarrow so that visitors had to look down to watch. On the monitor several of the group’s activities played under the common slogan “Shuangfei Debauches You” (Shuangfei huangyin ni, a play on the Olympic song “Beijing Welcomes You” Beijing huanying ni), more a corruption of pop culture than an exercise in art. If today there is still such a thing as a zeitgeist, for better or worse it has probably been picked off, leaving only nonsense humor; everything else gets played. The grassroots cred of such nonsense humor provides it with an unbeatable sense of security—itself a product of satire, it cannot be made fun of by anyone else. It’s hard to parody a parody, because the object of parody must be something of value. Deconstruction has no substance or theme in and of itself; it requires an object to prop it up, and is stable only because it leans on others. Performing its own levity, making all efforts at criticism look too fussy, too serious, and therefore too simpleminded, parody gets laughs, and laughs are affirmation, never mind to what degree. But perpetual reliance on others is just like looting, deforestation or mining coal—it is unsustainable. Logically, deconstruction necessarily awaits the arrival of construction; in the end there must be people willing to get serious, as there are so many things that need to be done besides parody.

Lu Yang, Li Ming and Guo Xi are three artists whose work in this show stood out and who have started to form their own identities. Lu’s sketches, resembling illustrations in a medical textbook in their careful accuracy, carry a sense of form, their content aggressive and provoking: a finger-guessing game machine and an underwater ballet troupe of frog corpses, along with detailed illustrations of the works’ underlying biological principles. Lu’s work brings to mind the coldness of early-period Zhang Peili as well as “Post-Sense Sensibility” in its use of human remains as material; its only problem might be Lu’s lackluster understanding of science as revealed in the sentence “Looking for scientists to collaborate with.” Realizing Lu’s plans is a question of technique, but for scientists the pure pursuit of “visual effect” likely holds little appeal and represents a deviation from the very value and meaning of science. When Lu’s work attempts to challenge the lower limits of morality or use cold detachment for political posturing, it runs up against a common problem for contemporary artists—the gap between visual form and meaning.

Li Ming’s eccentric work in the men’s restroom presented a tree painted black, dark-colored women’s underwear stretched tight with wire and a video playing of the artist next to them, his head covered with his clothing, crawling around naked in the space to rhythmic and effective background music.

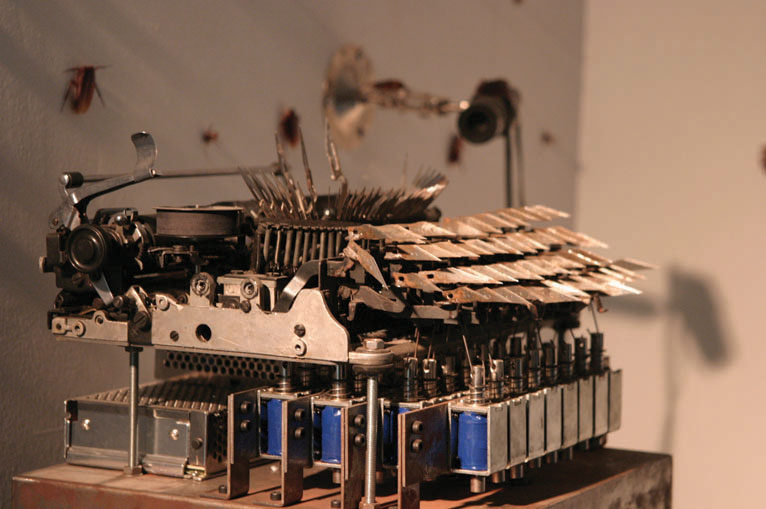

In Guo Xi’s Death of a Typist, an old-fashioned typewriter was hung in midair against the wall, typing away endlessly, but with all of the keys replaced by sharp razor blades, the act of typing turned into a violent flashing of razors, and all around the typewriter, on the wall and the floor, lay headless cockroaches. The work was built around a story the artist invented about a collaborationist Chinese translator in the Japanese army during the Second World War, for whom the artist has created Wikipedia and Baidupedia pages.

“Youth in Combustion” only lasted for three days in the area where artist Shao Yi keeps his studio, a somewhat desolate “science park” in Hangzhou’s Binjiang District where one could see workers packaging products in a nearby factory. A previous studio of Shao’s was Small Productions’ first hangout for planning, events and shows, but in a departure from the group’s spur-of-the-moment style, the brief nature of this show was born of more practical limitations imposed by the factory owner from whom they had borrowed two floors space and the expense of providing guards to watch after the works. Another reason for the show’s brevity was that practically all of the people in Hangzhou who should and would visit such a show were present at its opening, and a longer duration would not have brought in any more visitors. In this way the exhibition was more of a prepared statement for the crowd and not an event that should or would necessarily occur normally in the professional art system.

Youth is an excellent subject, though after viewing the show I started to long for something “beyond youth.” Perhaps I can appropriate Nietzsche’s foreword from The Case of Wagner: What does a young person demand of himself first and last? To overcome his youth, to become “timeless” (ageless). With “what must he therefore engage in the hardest combat? With whatever marks him as the child of his time.” Liu Tian