ZHOU TIEHAI: DESSERTS

| June 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 3

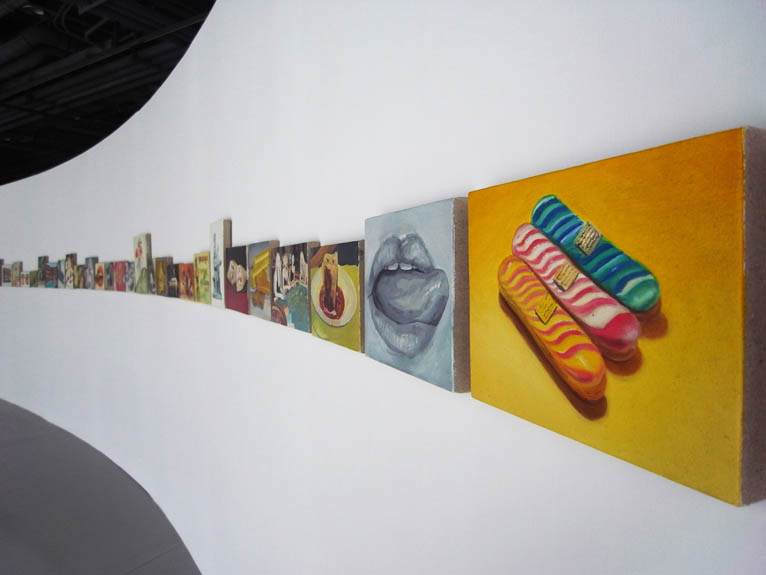

The latest incarnation of Zhou Tiehai’s ongoing Desserts project is a gorgeous confection mocking authorship, politics, fashion and self-importance. Hundreds of small-scale canvases were hung in a sweeping ribbon up MoCA Shanghai’s Guggenheim-ramp pastiche. The paintings are lovingly clichéd, depicting extra-sweet bourgeois images, whether a dainty cupcake, a French pâtissier tasting a sauce, or a pair of lipstick-painted lips biting a cherry. Replicas of academic drawings and erotic miniatures by French artists such as Fragonard hang alongside dislocated cartoons. Masses of girls lounge, pout and pose with ice cream. Man Ray’s iconic Surrealist photograph, Violin D’Ingres (1924) is quoted. In one possibly key picture, we enjoy a bird’s eye view of what appears to be the Pantheon, the mausoleum of many of France’s cultural heroes, including Voltaire.

Although he trained as a painter, Zhou Tiehai is best known for not painting his own work, choosing instead to approve the images, sit back and supervise production by a team of assistants. Up to now the most prominent example of this process was his “Camel” series, in which he appropriated the cartoon character, Joe Camel, from cigarette advertising and superimposed him into copies of masterpieces (particularly French, such as David’s Napoleon and Manet’s Olympia), supplanting the subject with the slick sunglass-wearing camel. “Desserts” remains true to the tenor of this conceit.

Here Zhou Tiehai presents us with a cavalcade of French political, social and cultural clichés, and not just in the paintings. At the opening were served twelve custom-made desserts alongside an explanatory text in gilt French cursive, bursting with purple prose such that it might best be read as a florid parody of art criticism. The desserts were devised by Richard Toix, chef de cuisine at Passions et Gourmandises, a Michelin-starred restaurant in Saint Benoit, France. The texts, for that matter, were written by Gu Leike, once a young French critic on the Chinese art scene who returned home to pursue a career in the academy. Each delicious dessert was given the name, in French, of a “profession”: diplomat, judge, minister, professor, policeman, sycophant, dancer, washerwoman, financier, buffoon, ragman and bottom-smacker. On opening night, MoCA was full of Shanghai (expat) society, including not a few diplomats and lawyers, connoisseurs all. The desserts satirize a certain bourgeois comfort, but also riff very literally on the notion of taste-making: what is good, what is bad, what is aesthetic and exclusive, and ultimately, what is allowed to be said.

Once asked about the point of this project, Zhou Tiehai responded, “To make sweet things for Westerners to taste,” a statement perhaps best read as a rebuke of Chinese contemporary art in the 1990s, the period during which Zhou emerged. As a corollary to this desire by Chinese artists to please, reviews of Chinese art for Western consumption have seemed to require philological comment (the present one no exception). Zhou subverts this whole logic; there is no order to the pictures aside from that imposed by the text, written in a language he does not himself speak. There are certainly no recognizably Chinese elements. Any narrative order to the random hanging sequence must be imposed by the viewer, leading to a certain frottage, less among the paintings than between the paintings and the viewer.

But don’t get lost in the vertiginous interpretations and narcotic familiarity of the imagery, even if that is partly Zhou Tiehai’s intention. In the tradition of Voltaire, Rabelais and Molière, he is parodying society in general and making fun of us, dear Viewer, in particular. He offers no comfort, no explanation. His insincerity is quite sincere. Thus the text is at once a crucial insight into the exhibition and useless ephemera. While the show muses on the exporting and mythologizing of cultural values, it is also pure double entendre. Reputedly when Zhou Enlai was asked about the significance of the French Revolution, he wryly replied that it was too early to say. This Zhou probably concurs. Wryly. Chris Moore