17TH BIENNALE OF SYDNEY

| August 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 4

The full range of discussions regarding the merit and worth of “the biennale,” whether concerning spectacle, universal precarity, making worlds, cultural tourism, consumer culture or “the new,” in what is effectively a global competitive market, all surface in this year’s Biennale of Sydney, and not just in its hyperbolic title, “Beauty of Distance: Songs of Survival in a Precarious Age.” Artistic director David Elliott, well known around the art world as founding director of the Mori Art Museum and the Istanbul Modern, focused on Sydney “as an iconic world city,” declaring that biennales should enter more into conversation with the places in which they unfold. Yet, in focusing upon Sydney Harbour and eschewing the greater environs of Sydney and its population (neglecting its original vision), cultural tourism appeared the key factor in its sponsor’s and Board’s envisioning.

This year’s biennale, the seventeenth in thirty-seven years, was the largest yet, including four hundred-forty works by 166 artists and collaborators from thirty six countries. But the biennale’s size, along with the unabashedly “tourist” bias in selecting Sydney Harbour venues such as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Opera House, Artspace, Pier 2/3, and, most overtly, Cockatoo Island, seemingly dissipated any sense of thematic unity. The works simply did not aggregate to match the grand hyperbole of its titular theme. Herein lies a fundamental historical problem with the Biennale of Sydney. Its presentation of art from Asia has been minimal over time (except for the critical Zones of Contact by Charles Merewether in 2006, which introduced new artists from greater Asia, ex-Communist countries of Eastern Europe, and the Middle East), stoically maintaining itself as a European cultural outpost surrounded by a legion of Asian biennales. (Brisbane’s Asia Pacific Triennial, inaugurated in 1993, focuses its scrutiny toward the North, in complete antithesis to Sydney.)

The director proposed in his pre-launch media release that the “distance” of the biennale’s title allows “us to be ourselves despite the many capacities we share,” exaggerating our more dramatic qualities. It thus expresses “the condition of art itself—art is of life, runs parallel to life and is sometimes about life.” In determining that art must maintain a distance from life, Elliott advocated that without distance, art has no authority and is no longer special. “As art depends on the beauty of distance, beauty in art depends on distance as well.” The subordinate thematic, “Songs of Survival in a Precarious Age,” advances the affirmative power of art in the face of unprecedented threats: conflict, famine, inequity, environmental despoliation and global warming. Elliott emphasized that his “Beauty of Distance” looked toward the future, but in asking how much have things really changed in our world of transformation, the art on view was inevitably formed by different experiences of the past.

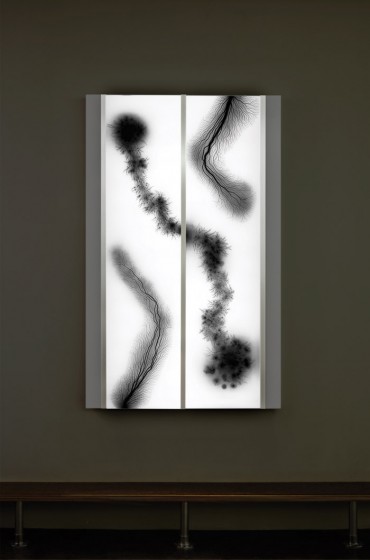

Despite the biennale’s lack of thematic cohesion, it still had its resonant individual artworks. As in every biennale, the artists, placed in competition with the historical and physical environments of the biennale sites, either struggled or dazzled. This was most evident at Cockatoo Island, a former convict gaol and Naval ship repair yard in the middle of Sydney Harbour, with its monumental infrastructure. There, Cai Guo-Qiang suspended from the ceiling of the Turbine Hall his nine-car installation Inopportune: Stage One (2004), representing an exploding series of cars rotating through space. While Cai’s work was presented as meditating upon the beauty and horror of destruction, as well as terrorism and the current war against it, cynics might have ventured otherwise given the overwhelming muscular volume of the building. Elsewhere on Cockatoo Island, Hiroshi Sugimoto presented inside its defunct Power House an installation of light-boxes, showing abstract photographs of electrical discharge from his “Lightning Fields” series, recent experiments in imaging electricity on large-format film that explore the relationship between light, energy and power—ascending towards a thirteenth-century Japanese sculpture of Raijin, the Japanese God of Thunder. While a magnetizing work it was somewhat overpowered by its Frankenstein-esque movie-set ambience.

Yang Fudong’s East of Que Village (2007) is an agonizing multi-screen monochrome depiction of rural poverty in northern China, juxtaposing scenes of dogs dying from starvation with everyday human activities in a forbidding landscape, paralleling both to the same level of hardship. And yet of all the works on Cockatoo Island, British artist Isaac Julien’s new Ten Thousand Waves (2010) was the standout, alone worth the romantic ferry ride across the harbor. Exploring diaspora and migration through a story entwining legend and modern China, the nine-channel video work is inspired by the deaths of Chinese illegal migrant workers who drowned in England in 2004. In tracing the workers back to their origins, culture and history and using the image of water—the sandy waters of Lancashire, the Yangtze River and the Shanghai Bund—as a symbol of danger, trade, modernity, mystery and economic power, Julien leads the viewer through a story that examines the needs and desires that drive people to undertake perilous journeys to achieve a better life. It’s an extraordinarily captivating work, not to mention the ethereal white-robed presence of the Chinese actress Maggie Cheung.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art, Shen Shaomin presented new work that continues his tortured “Bonsai” series as a comment on the despoliation of the environment, and the painful aspects of beauty and control in society, while on Cockatoo Island, Shen showed Summit (2010), featuring a hypothetical meeting of the corpses of the most significant communist leaders in history, conceived in part as a response to the global financial crisis and the apparent failure of capitalism. Elsewhere, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu presented Hong Kong Intervention (2009), a photographic series that conjectures upon the everyday lives of Filipino domestic workers in Hong Kong. By inviting one hundred Filipino workers to place and photograph a toy grenade in their domestic work environment, the playful yet sinister series examines the phenomenon of workers living away from home and their fraught integration into the domestic spheres of others. Still on the Sydney Harbour circuit, Artspace became home to a temporary outpost of the Tokyo venue SuperDeluxe, hosting performances, artist presentations, and Pecha Kucha nights.

Despite the feel-good response to the Biennale of Sydney by the media (“art is fun”) and its populist cultural tourism outcomes, one senses here a “biennale brand” in the making. If the following edition is yet again under the helm of another Euro-American as is touted, then it would seem that the Biennale of Sydney is firmly fixed upon its origins without acknowledgment of its place in the region. Alan Cruickshank