CHEN CHIEH-JEN: MEDITATIONS AT THE MARGINS

| February 9, 2011 | Post In LEAP 7

Chen Chieh-Jen’s works Empire’s Borders I (2008-09) and Empire’s Borders II (2010) use images to address the modern critical construct that is “empire.” Modern leftist thinkers’ sustained consideration of “empire” seeks to excavate its internal contradictions. And just as Slovenian intellectual Slavoj Žižek posits, the true problems of empire lie with the world police: the United States. It is not in the service of its imagined territory that this global empire strives for profit, but in the service of the American nation-state. Consequently, the subject becomes inscribed within the borders of this mythos.

1. Whose Empire? Whose Borders?

The experience of a visa interview is the point of departure for Chen Chieh-Jen’s Empire’s Borders I. As the creator puts it in the text accompanying his work: “The visa interview system is not just the exercise of a sovereign state’s powers to monitor and control movement through its borders; it is a strategy by which strong countries discipline the peoples of weaker countries, and a technique by which ‘empire’ governs the people of the world.” It is behavior along borders that imbues them with significance, and transforms people’s attitudes into symbols of the border.

When shooting Empire’s Borders I, Chen Chieh-Jen constructed two “scenes,” one at the American Institute in Taipei (which serves consular functions, since the territory does not have diplomatic relations with the U.S.), and another at an airport. In the first part of the work, eight women face the lens in the interview space of the American Institute, recounting their experiences of visa rejection. Theirs are grievances of the periphery suffered through attempts to return to the center. Going to the United States is understood by the departee to be an act of identification, one whose unexpected rejection swiftly renders the boundaries of empire in sharp relief. This empire surprisingly cannot place itself within the boundary line, or what is understood as “within.” To be classified as “within” is perhaps even more humiliating. The images in Chen’s scenes become a mirror through which the women see themselves. The power of the gaze intensifies their humiliation and self-pity. Humiliation and self-pity in a clean, cold space—appearing in close-up shots on a monitor—accentuate the female’s status as the weaker sex.

The second part of the work once again features eight women, this time in the customs line for non-citizens in the Taipei airport. Their hands pushing luggage carts, they read aloud the lines written on the back of an entry form. Apart from the women being noticeably older than in the previous section, various Chinese dialects also make an appearance, marking these women as PRC citizens looking to enter Taiwan. Here, going to Taipei is not portrayed as travel from the heart of an old empire to its fringes, but rather as stricken with the diverse internal problems of a large cultural zone, a profusion of regional dialects being the most salient sign of this multiculture. The women are gathered in protest, reading aloud from the papers they hold, each standing together with the others, accentuating the sense of grievance.

In Taiwan, the three territories—Mainland China, Taiwan, and the United States—come together to form a dual boundary. One aspect of this dual boundary is a liminal space between opposing camps created by the Cold War, another the issues of internal division that are the legacy of World War II and China’s internal political struggles. This dual boundary delineates Taiwan; that is to say, Taiwan’s position is a marginal one, a position on the outskirts of thought and ideology. In such a space, carving out room for Taiwan is particularly complicated and contentious.

Chen Chieh-Jen’s work manifests the cruelty of warring ideologies through its women. All of its narrators are women, and within the works, women come to represent weakness. One aspect of this weakness is the internal weakness of empire, another the weakness within cultural circles. Yet another aspect is the weakness of gender. An important reason for the rejection of these Taiwanese women’s applications for an American visa is their single status, which marks them as “immigration risks,” while the reason for the investigation of the Mainland spouses is that these women have, in fact, already become a resource, a kind of presence in Taiwan. At the level of this cold-blooded investigation, women’s bodies and voices become the best way by which this boundary can be acted out. That these women’s bodies cannot be controlled represents a softening at the boundaries of empire.

In Empire’s Borders I, the boundaries between scenes become the boundaries between ideologies, finally becoming the boundaries between genders. In its structures of politics and power, women are the sole performers, no matter whether in humiliation or self-pity, denunciation or protest.

2. Why Narrate? Stories of Dual Ruins

Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. recounts the story of the eponymous “Western Enterprises,” an entity established by the CIA in Taiwan in 1950, at the onset of the Korean War. Western Enterprises’ main tasks included working with the Kuomintang to train an “Anti-Communist National Salvation Army” for an attack on the Mainland, and establishing Taiwan as a base for anti-communist operations in Southeast Asia. The work is narrated from the point of view of the artist’s father, once a member of the Anti-Communist National Salvation Army, reconstructing history on the ruins of the old Western Enterprises base of operations.

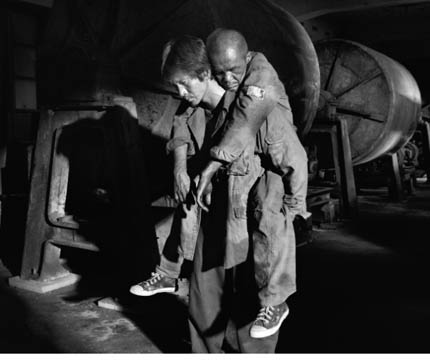

The first scene from the work is a reconstructed archive room, piled high on both sides with files. In the middle of the room is an incinerator. Accompanied by the dubbed-in sound of a low-frequency hum, the camera creeps forward. The work is a plea born of buried historical memory. Starting from the room of Chen Chieh-Jen’s father (their relationship isn’t explicitly spelled out anywhere in the work, I just imagine it that way), he and his associates work their way through the space, incinerating as they go. Some of the documents burned are albums, others headshots of young people. Chen’s father wears an old military uniform, while the walls around him are hung with photos of past leaders. The surroundings draw him towards a building. Above its crumbling entrance is hung a sign that reads “Western Enterprises Inc.” He walks inside where his companions will find the documents they seek and carry away their brothers to sea.

With a little patience, I could easily describe Chen Chieh-Jen’s work in its entirety. That is to say, the appeal made by the work’s narrative is plain for anyone to see. Viewing it, I get the same feeling I did upon seeing his previous work, Military Court and Prison: purpose, expression, all swept up in the narrative logic of scene sequence. Historical reconstruction becomes linguistic mechanism. Historical reconstruction lends itself naturally to narrative process, falling easily into sets of linguistic logic. A bird’s eye view of history becomes a form of appeal, an appeal to logic. The visual language of Empire’s Borders II recalls classic Hollywood. We observe with extreme clarity when characters enter and exit the frame, materializing in a powerful sense of the camera’s gaze. Although the delicately constructed imagery and the old Hollywood visual vocabulary are damaged by a vague plot and the insertion of visual symbols as metaphors, on the whole, the logic of Empire’s Borders II is almost entirely plot-centric in its design, which reveals a conceptual overlap with Empire’s Borders I.

I find this kind of clear-cut logic oppressive. I am forced to reflect on the piece’s internal logic, to let the cloudy images of memory come flowing back. Chen Chieh-Jen’s father and his comrades-in-arms advance down a path. On a sign along the path we can see printed the blue and white of the Kuomintang flag, along with the words “Military Assistance Advisory Group”—a term used since the end of the Second World War to describe American military groups sent to foreign territories in training and advisory roles, Taiwan among them. As soon as people begin to pass along this road, we see them begin to move into the incinerator space. They discover two prisoners there, labor union members apprehended by the military. One of them, a man, they save. The other, a blindfolded woman, they leave. They travel back along their original route, passing piles of obsolete, abandoned mechanical equipment. These documentary-style images and arranged scenes form a group of images (the subjects of these scenes carry cardboard signs with characters specially written on them with meanings unclear to me). In this section appear images of labor, and American and Taiwanese economic development. Finally, the piece again ascends to the roof of a building, where its subjects gather in an auditorium-like space. In the space have been left old photos from that era, while from the ceiling are hung colored silk balls traditionally used for decorative purposes. On the walls at the front of the space are shabby-looking colored ribbons. In this ceremonial space, the film’s subjects begin to move upward, gathering on the space’s stage. Close-ups of legs moving upward emphasize the piece’s narrative logic, and form an expressive final footnote. These people, made invisible by history, have brought themselves to light.

The piece’s brilliant thesis emerges in its final shot. In a tight close-up on the face of Chen Chieh-Jen’s father, we see him think back to that forgotten woman, blindfolded and imprisoned, then to an incineration oven belching smoke. The camera, tracing a horizontal line across the room, tilts upwards (we can see the four Chinese characters for “Western Enterprises”). The power of this finale lies in Chen’s attempt to enter the narratives of self-determination of his subjects, and to restore histories once obscured by power. It must be noted the means of this restoration is a kind of classical narrative certainty. At the same time a kind of self-reevaluation emerges, an intuitive understanding and examination of ourselves found in the process of constructing history. Chen’s father discovers the people he and his companions left behind. That this discovery is resistance to history’s incinerator, as well as a way of transcending the materiality of historical constructs, is the essence of Chen’s work. Here, the narrative language of classic cinema emphasizes the constructed strength of the relationship between that which sees and that which is seen. This edifice is beyond any doubt, as those who illuminate history discover when they ascend the stage to find, completely abandoned, a woman.

The set of Empire’s Borders II reconstructs the space of the Western Enterprises building. This reconstruction takes place inside of an old factory. It is not, however, a complete reconstruction. It is the reconstruction of the ruins of a Western factory inside the ruins of another old factory. The concept of “ruins” in Empire’s Borders II is two-sided. Among the ruins, Chen Chieh-Jen constructs, on the one hand, the ruins of a Cold War-era political and military base, while on the other the work preserves, as an economic record, industrial relics. In carrying out this preservation, Chen does not stop at a simple nostalgic viewing of discarded machinery. On the contrary, he adds another dimension to his work by layering a previously lost political and military history atop the vestiges of raw material. Truth be told, Taiwan’s current post-authoritarian economic rise is built on dualities like these.

In Empire’s Borders II, ruins, spirits, and the testimony to vanished histories form a recollection of a Cold War-era forward operating base. Here, the memories of particular histories become a meditation on those who came before, a meditation that gives voice to those things the generation prior did not have words to say. Chen Chieh-Jen succeeds completely in transforming individual histories into a larger historical discussion. The work’s final pairing of individual characters, a fugitive man and his fleeting thoughts of a female prisoner, orients, once and for all, man in his grievances with history. Though caught under the crushing wheels of history, man is still both its driver and object. While Empire’s Border’s I is the story of a group of women, Empire’s Borders II strikes me as the work of a son recounting the history of his father’s generation. The images become a sort of spiritual skin, and the work they make up becomes a face that the artist presents to the world.