SUN XUN’S FIRST FIVE-YEAR PLAN

| April 19, 2011 | Post In LEAP 8

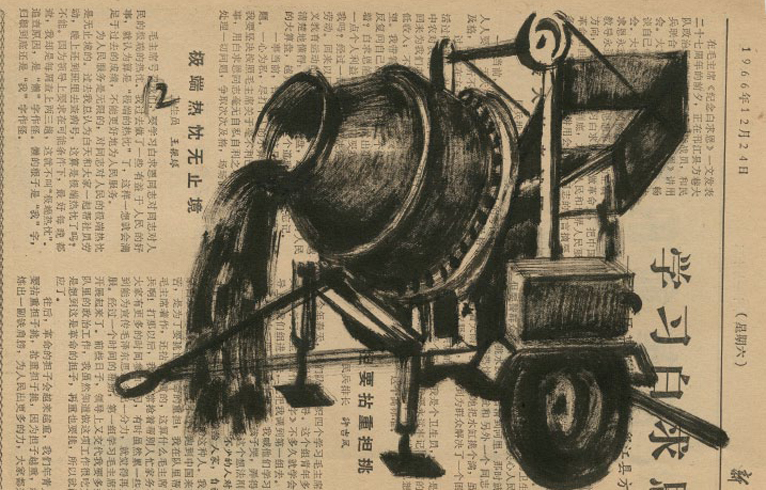

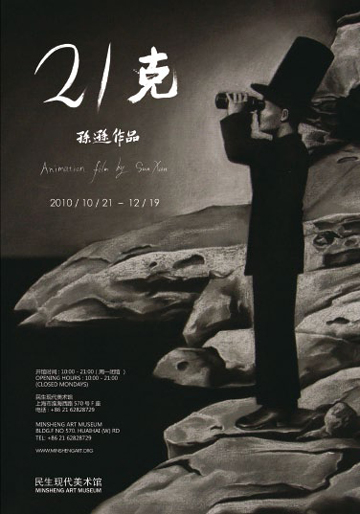

In 2006, Sun Xun founded π Animation Studio in Hangzhou. The 2005 graduate of the China Academy of Art was anxious to build his own studio so that he could begin work on a high-quality animated film. The 27-minute, 50-scene film— entitled 21 Grams and featured in the “Orizzonti” section of the 2010 Venice International Film Festival— was originally slated to take two years to produce. But owing to Sun’s lack of experience at the time, it ended up taking four. It was only after drafting an extremely meticulous hand-drawn outline of the film that he realized how immense a studio he needed to pull it off. During production, the π Studio team gradually expanded to include more than twenty people, and eventually moved from Hangzhou to Beijing, occupying a row of four standard-sized studios in the Heiqiao district favored by young artists in the capital.

Looking back, as the studio had been inadequately prepared to create 21 Grams, the process brought about a number of changes, some rather conspicuous. According to Sun, these changes were necessary if only to produce the thirty thousand still frames which make up the film. But most importantly, although perhaps not immediately apparent, he constructed a series of systems for his artistic practice that implemented new creative, operational, and managerial ideas. These, perhaps even more than the films themselves, are the key achievements of Sun’s “First Five-Year Plan” for π Animation Studio.

In China since 1949, the term “Five-Year Plan” (changed to “Five-Year Guideline” in 2006) has become well known among the people. It recalls an earlier moment of a planned economy, beginning with the First Five-Year Plan (1953-1957), and yet remains the Chinese government’s method for setting the basic macroeconomic objectives for the development of the country in any given period. Primarily, these initiatives focus on setting long-term standards and strategically planning large-scale national construction projects, distribution of production, and key economic ratios. The year 2011 marks the beginning of the Twelfth Five-Year Plan. Sun Xun’s use of this term to name his own work from 2006 to 2010 is a clever reminder of how multiple temporalities seem to coexist in today’s China—harkening back to an earlier era even as it continues to articulate the contours of the immediate future. Sun’s “Five-Year Plan” seems to get at the unique combination of nostalgia and ambition behind each of the many animations, prints, installations, and sitespecific projects he realized during that period.

Among the ten works made under the π banner, from Shock of Time in 2006 to Beyond-ism in 2010, the only work truly propelled by the collective force of the entire team was 21 Grams. The rest were either completed by Sun Xun him self or with the assistance of a few assistants, and cannot be considered animated shorts. The period following the completion of each of these, too, duly conformed to the exhibition paradigm of the contemporary art world. On this point, Sun maintains a frank and pragmatic attitude: when one is incapable of financially supporting oneself, the capital needed for making a feature-length film like 21 Grams can only be procured from the commercial system of contemporary art. Most of the time, in other words, this isn’t a test of Sun’s creativity, but rather, of how to squeeze production resources out of exhibition budgets. Indeed, these days it seems that the key to a successful working method resides in the efficient operation of the studio.

As Sun Xun’s longest animation to date, 21 Grams can be regarded as the most representative work of his “First Five-Year Plan.” But as one of all the works produced during that period, the true meaning of the film lies almost more in the fact of its having been completed than in the breakthrough individuality of its ideas. Perhaps this interpretation is rooted in the displacement of time and space as inspired by the long, almost endless process of the film’s creation. As strictly as it followed a fixed script and visual style, the film never saw Sun deviate from his other projects, even as it approached completion. It was as if he had mastered the mythical Chinese technique of splitting himself in two as he constantly made detailed elaborations on the themes of 21 Grams in the other short films. It would seem that these elaborations ought to be a follow-up, a set of proofs of ideas most clearly made manifest in 21 Grams, but of which earlier examples can be found in Shock of Time and Mythos (both 2006). It only goes to say, then, that when it was completed in 2010, 21 Grams served as an introduction to these earlier works, albeit a belated one.

Sun Xun had already begun writing this “introduction” much earlier, in between Shock of Time and Mythos, setting out to explain all its corresponding ideas in conscientious form. For example, the image of the magician— carrying his cane, wearing a top hat, donning a tailcoat, and with mosquitoes for cronies— is connected to “the only legal liar,” appropriated as the vehicle for the “dissemination of lies.” In reality, this is the starting point for the construction of Sun’s overall artistic system. Whether it’s Shock of Time, Mythos, or 21 Grams, all three films are similar in concept: Each conveys to the viewer Sun’s overall apprehension toward the presentation of history. In the opening and closing credits of Shock of Time, two questions are posed: “History is a lie of time?” and “Mythos can expel truth?” In 21 Grams, then, it would seem that Sun asks himself these questions, and answers them too.

From the outset, the conspicuous reference to the soul in the title “21 Grams” affirms the film’s concern with the spiritual world. As far as content is concerned, the film clearly aims to focus more on contrasting scenographies than did Mythos. At the same time, however, it moves away from the specific spatio-temporal references of the earlier work. Although the appearance and reappearance of the magician and the mosquito set them up as key images, Sun Xun is most clearly interested in what he calls the “lie of time,” in the multiple dimensions that exist between us people and the objective world. It is just as when the seven seas and five continents are reorganized into a new “world map” in the opening sequence of the film, and the words “their world is like this” appear to remind the viewer of the ultimate contingency of geopolitical boundaries. Such depictions of space and existence are the primary method through which 21 Grams reveals its attitude toward these layered and complex relationships.

Thus, Sun Xun never explicitly outlines a so-called “spiritual world.” Instead, he has taken that world and un- derstood it to be a method and perspective from which he may relate to and change this world, such that the world in 21 Grams ultimately turns into a jumbled realm of symbols. At the end of the film, the lighthouse flashes out the word “revolution” in Morse code as a man is shown facing the ocean and crying his heart out. This pessimistic conclusion thus submerges “their world” into the utter hopelessness of history, and Sun once again fully confirms, and reveals, the core concept of his artistic system.

The commencement of 21 Grams can be regarded a turning point for Sun Xun’s “First Five-Year Plan,” and all preceding and subsequent changes took place in a conscious decision to transform himself from artist to filmmaker. This transformation stresses the power of action, and of execution. Sun hasn’t merely established an intricate management system for π Studio— so intricate, in fact, that not one detail, including the management of scheduling, work attendance, custodial duties, finances, and even of the cafeteria, has been overlooked. He has also established positions, workflow systems, and internal evaluation mechanisms specifically tailored to the demands of animation. But as he also resides in yet another “ecosystem,” Sun more often than not must transport the animation studio to the exhibition gallery, such that his shows become visual spaces comprising an amalgam of installations, paintings and animations. This practice pertains without exception to the reasoning of contemporary art; one the one hand, it enhances viewer experience; on the other, it realizes the diversity of the language of animation. In recent years there have been exhibitions to accompany each one of Sun’s animations. “Coal Spell” (Beijing, 2008), “The New China” (Los Angeles, 2008), and “After Doctrine” (Yokohama, 2010) were three of the most exemplary. Take, for example, “After Doctrine”: the ten gigantic (5 x 2 meter) ink-and-wash paintings used to cover the windows of the Yokohama gallery were also the core elements of the animation on display, an exhibition technique which visually connected and sustained the entire show. It goes without saying that the Sun Xun of the “First Five-Year Plan” successfully made the frequent transition between the two “ecosystems” of animation-studio production and art-world display. The real difficulty now lies in the fact that such toggling seems to have become excessively frequent. Perhaps solving that problem will be the key objective for Sun’s “Second Five-Year Plan.”