SHARJAH BIENNIAL 10: PLOT FOR A BIENNIAL

| July 11, 2011 | Post In LEAP 9

The Sharjah Biennial was hardly the biggest thing afoot in the Arab world this spring, even if the halo effect of the concurrent Art Dubai seems to have tipped it over into critical mass. (The 2011 iteration of both shows were the largest in their respective histories). Of course, any historic change is inseparable from changes in the thinking of the wider population. With that in mind, any observer would be hard-pressed not to admit that, as far as valuable windows on Arabic culture go, Sharjah is hard to top.

Now in its twentieth year, this modern art biennial was staged with the support of the Sheik of Sharjah and the Sharjah Art Foundation. The majority of the artists chosen, some of whom the foundation subsidizes, are from Egypt, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, and other countries in the area. They come from different national backgrounds, and different personal and creative circumstances. Some left their homelands for the Emirates in search of the shelter afforded by new oil wealth. Others have transcended their ethnicities to become citizens of a global age. The national, the ethnic, and the individual— both past and present— are ever-present in their work, making the modern art in the Arab world unusually rich and diverse.

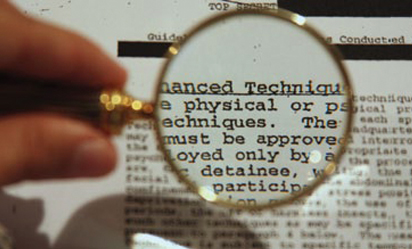

The masterminds of this year’s Biennial were Suzanne Cotter, Curator of Exhibitions for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Project, Lebanese curator Rasha Salti, and their young, globe-trotting assistant curator, Haig Aivazian. In constructing the Biennial’s narrative, the three curators tore a page from the movie playbook, using the idea of “plot” as the framework for their exhibition. The heart of their plan was a series of “keywords” designed to tap into the fears of the wider society (“Treason,” “Necessity,” “Insurrection,” “Corruption,” “Devotion,” “Disclosure,” and “Translation,” all apt choices in a time of flux).

The fingerprints of their brainstorming sessions were all over the curators’ formal description of the Biennial, and their chosen framework sounded (at the very least) like a forward-thinking choice. The exhibition’s “March Meeting,” its associated publications and movie screenings, music and dance performances, the majority of which were specially commissioned, made this Biennial an unusually deep, unusually layered one. Still, what most captivated the first-time visitor was the exhibition’s use of geography and space.

The curators chose to scatter a portion of the Biennial’s works and activities throughout Sharjah’s old city— currently under renovation— from the old quarter’s still-bustling traditional market to the ruins of old mansions, spread across a section of town now designated as the “Arts and Heritage Area.” In past decades, these areas, so representative of the urban Gulf culture of yesteryear, were Sharjah’s beating urban heart. Now they have become “heritage,” swiftly made so by the changes wrought in the capital by the oil economy.

A number of the commissioned works spoke to the artists’ reaction to the exhibition’s surroundings. Blessings Upon the Land of my Love, a work created by artist Irman Qureshi in the central courtyard of the Bait Al Serkal (once the dwelling of the Serkals, a prominent local family), was particularly unforgettable, drawing in the viewer with its deceptive violence. The artist dashed the inside of the courtyard with splatters of what looked like blood. After a step back, though, and the pattern became apparent: what looked like bloodstains was actually a chain of flowers.

In the same building, the Iranian documentary pioneer Kamran Shirdel’s 1975 work Pearls of the Persian Gulf: Dubai 1975 showed viewers, through the lens of Dubai, the culture and natural vistas of the UAE before oil and finance made it a country of skyscrapers. The film may be of especial interest to viewers of Chinese extract, as it and China, the famed 1972 documentary by Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni, met an especially similar fate. In the filming process, both documentaries were the beneficiaries of fervent support of the subject nations’ national governments, both of which banned the completed documentaries following their releases. Just as obvious to today’s viewer are the directors’ affection for their subjects, and the poetic way it finds expression.

With the world as it is today though, modern artists have a difficult time taking Karman Shirdel’s view of things. In The Neighbour the House, a 45-minute documentary by the Bombay art collective “CAMP” (commissioned in 2009 for “The Jerusalem Show”), the artists succeed in convincing Palestinians living in Jerusalem to carry security cameras in search of their former homes. With an accompanying narration, they seek out and focus in on the visual proof of their own historical narrative. The low resolution of the cameras and the harsh pans and zooms strip the film of any pretense of beauty or poetry, but in the dual perspective, of the CCTV cameras, both voyeuristic and vigilant, the artists’ message comes across crystal clear.

Countless, omnipresent digital cameras and CCTV are the expression of a government and a population uneasy about terrorists and criminals; or so says the multimedia visual installation work Face Scripting: What Did the Building See?, which combines fact and fiction to analyze last year’s assassination of a Hamas member in Dubai. Apart from the artist’s visual recreations of the scene of the assassination, the installation includes airport surveillance footage leaked onto YouTube. Exhibition and observation, movement and surveillance: the way a work— or an exhibition— structures its lines of sight is a small-scale version of the thing itself (and the conflicts and problems that this structure poses can themselves prove to be the most interesting part of the work).

At the Biennial press conference, the focus of the assembled journalists centered on a few works that were pulled from the exhibition at the last minute. But it wasn’t until the majority of the guests had left that the real “incident” erupted: Jack Persekian, the chairman of the Sharjah Art Foundation, was removed from his post, without even a formal notice of dismissal from the foundation.

As someone not steeped in the local language or religious culture, I am not in any position to judge whether or not the works in question were “ticking time-bombs,” waiting to erupt into controversy. And when judging a work that presses the public’s buttons, it’s always best to first understand the motivation behind the work (because, after all, the equation of broken taboos with success occurs all too frequently in the contemporary art world).

But, where the Biennial is concerned, after such long, painstaking effort towards opening channels for dialogue and communication (an effort in which Persekian played a particularly outstanding role), such extreme action is a particular cause for pity. Just a small misstep can result in the loss of much hard-won cultural progress, a result that no one involved wants to see.