DESIGNING CHINA

| August 8, 2011 | Post In LEAP 10

ENMESHED IN MID-AIR: THE NANJING SIFANG ART MUSEUM

When Steven Holl laid eyes on his first commission in China, the site was “overgrown with vegetation— no roads, site boundaries, no clear site plan.” Initial plans called for an “Art and Architecture Museum.” That day, he “began making sketches . . . based on [his] understanding of axonometric perspective in Chinese painting.”

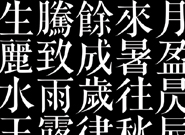

YING YUN-WEI: ANCIENT FONTS REMADE

In our information age, electronic media have changed attitudes toward traditional printed texts, and toward printed characters themselves. New technology has engendered a new aesthetic for character form, one that inevitably feels overly cold and rigid. Against this, traditional typefaces are starting to make a comeback. Ying Yun-Wei is one designer adopting traditional character forms to create new computer typefaces.

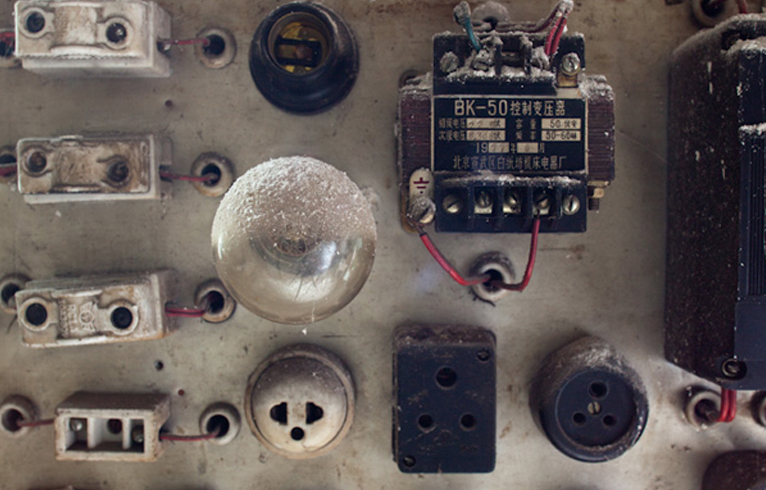

THE MUSEUM OF “DESIGN FOR THE POOR”

The concept of “design for the poor” was put forward in 2006 by artist Qiu Zhijie and a class of his design students at the China Academy of Art. It refers to the ways people at the bottom rung of society use design and manufacturing to meet the challenges of their everyday problems.

ffiXXed: FASHION, UNFETTERED

Shenzhen, the fishing village-turned-economic-powerhouse at the heart of China’s reforms, is best known these days for factories housing thousands, churning out tablet computers and smartphones for the desirous consumer masses. But on the outskirts of the city, since 2009, two Australian designers have lived and worked in a fashion atelier that employs not twelve thousand workers, but twelve.

BOUND FOR BEAUTY: NINETEEN NOTABLE BOOK DESIGNS

These are 19 of the most beautifully designed books we have come across in recent years. The majority are artist monographs or otherwise art-related, and some are publications on visual culture in general, but worth noting is that a good number of them are independently published. Most importantly, though, whether due to corporeal chaos or to reserved simplicity, we might surmise from these works that designers in China possess a much more solid and thorough understanding of books than ever before.

DASHILAR REVISITED

It may seem odd that among the highlights of this year’s Beijing Design Week (September 26 to October 3) will be the goings-on in a handful of empty, run-down spaces in Dashilar. But wedged between the faux-historic simulacrum of Qianmen Avenue and the vast socialist-utopian void of Tiananmen Square— and comprising of every stratum of Beijing’s past (making it a pastiche in the most authentic sense)— Dashilar can if anything be said to exist in a kind of in-between state. It is, like design at its most fundamental, a perpetual work in progress.