REPUBLICAN REVELRY: THE FUNHOUSE-MIRROR WORLD OF “GREAT WORLD”

| December 6, 2011 | Post In LEAP 11

Looking back, it is hard not to recognize the prescience of Shanghai’s early amusement parks. In the decades that followed, this festive mode of consumption rapidly spread throughout the world, becoming the anthem of entertainment for the urban middle classes.

THE SETTING SUN spread over the broad, flat asphalt road. Flocks of cars and people were out and about. It was the end of the year, and the road was busier than usual. A petit-bourgeois couple strolled along as if in a park, chatting as they sauntered down the street.

“Last year at this time, now that was lively! I didn’t dare go out. There were Japanese planes in the air, and Japanese soldiers at Jiangwan and Zhabei throwing bombs all over the place…” said Lao He.

“I’d much prefer last year to a year like this one! I’ve lived to 40, but I’ve only had one year as peaceful as that one. I’m in debt to the rice shop and to my previous landlord, and I have other debts as well. I’ve never paid off these debts, and there seems to be no hope that I ever will. So at the end of every year, I have to go hiding from my creditors.” Chun Sheng let out a sigh.

“You haven’t sorted out that business and you still have time to go with me to Great World to play around?”

“Oh, brother, what do you know about it? The creditors and debt collectors agreed to meet at my house tonight to get their money, but it’s not like I have it! So I could only invite you to Great World to walk around a bit or find a seat where there aren’t too many people and doze off. I can’t go back until after 12, and the winter weather is cold and wet, so where else is there to go? Only Great World.”

“Never mind them. Who’s to say that all of Shanghai won’t be underground before long? Didn’t Sincere, Wing On and Sun Sun all go under two years ago? The rich man’s heaven was built on the flesh and blood of the poor, and once the poor are all gone, that heaven will become hell. We’ll see!”

They had walked to the Dongxinqiao area. The two middle-aged people entered the gates to Great World, passing the signboard hung on the lintel that read “Make Merry Now,” and their shadows vanished as they passed through that gateway.

In the early years of the Republic, the main amusement parks in Shanghai were Tin Wan House, New World, Sincere Park, and Sun Sun Roof Garden. Tickets were cheap— about 20 cents in small silver coins— and the miscellaneous games and entertainments attracted laborers and other members of the lower strata. Louwailou, located above the Sun Sun stage on Zhejiang Road, was accessed by elevator and caused quite a stir in Shanghai for a time. New World, which was located in Jing’ansi and operated by Huang Chujiu, was adjacent to the horse track. On one occasion, the park management purchased 100,000 used small boxes from Russia and filled them with candy as a promotional giveaway; as a result, they managed to sell more than 1,500 extra tickets in a single day. But the most prosperous of all was Great World, “The Biggest Amusement Park in the Far East,” with structures including the Republic Pavilion, Observation Tower, Xiaopeng Mountain, Xiaolu Mountain, Sparrow Screen, Wind Hall, Shoushi Lodge, Panorama Dias, Screw Pavilion, and Cloud Stage. Great World even invited scholars to draft a “Top Ten Sights” for the park, using its creation to produce a true carnival for China’s common people.

At Great World, you were led by song, dance, and film— as well as bewitching women— to temporarily forget everything. It was a transient amusement that provided an escape from reality. The most popular attraction at Great World was the Shanghai Burlesque, which featured a crude clown act uncommon in the burlesques of that time. It was held at irregular intervals to commemorate all sorts of folk holidays, and, in conjunction with the nightly fireworks display, it truly felt like every day was a holiday. Moreover, in the early days, the Mao’er plays (a Beijing opera acted solely by young girls), female modern dramas, and bouquet concerts (featuring popular songstresses), and, in the later days, the “Streetwalker World” described by Cao Juren, all added a more-or-less pornographic aspect to Great World’s appeal.

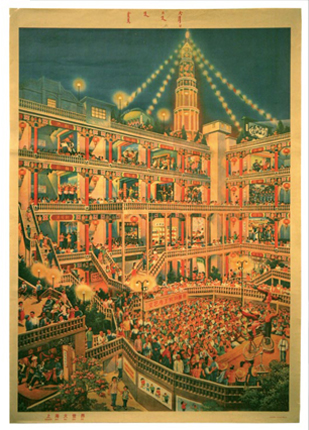

The inner park was constantly filled with the deafening sounds of gongs and drums; the courtyard area was the place for a breath of fresh air. Hanging in front of the north building was an extremely eye-catching neon advertisement with six characters reading “Namo Amitabha.” The central corridor was lined with benches on both sides, and whenever someone needed to take a seat, there would always be a woman to rush over and help locate an open spot. Shrieks of laughter rose up from the downstairs skating rink, drawing patrons toward it seemingly against their will— especially the well-to-do young men, free to glide around to their hearts’ content, entertaining the women present with their polished skating skills. As for those with refined tastes, they could ascend to the rooftop garden and enjoy a cup of tea among the chrysanthemums and cool breeze.

At Great World, the most grotesque roles with the most affected speech won the greatest favor from the audiences. The Beijing opera and modern drama theaters were attended by row upon row of women, mostly dressed-up concubines in their twenties and thirties. Out behind these venues were a different group of young ladies. Dressed in gay, modern apparel with their lips painted a frightening shade of red, some played the coquette to full effect, while others arched their brows and wore bitter smiles, sometimes leveling withering glares, and sometimes, under the direction of their procuresses, using their hands, eyes, and words in full-on assaults on passing men. If it were not for those ubiquitous procuresses, who could separate these women from the elegant wives and modern young ladies? But it was they who became the amusement park’s best advertisement, vivid, colorful, and free of charge.

Just within the gates of Great World, there were twelve funhouse mirrors, specially ordered from England, which reflected distorted images of the faces and bodies of visitors. It was as if one had crossed a border between everyday life and a carnival world. Whenever someone mentioned Great World, those mirrors would always come up. They found those distorted reflections so hilarious. Entering Great World meant entering a distorted, exaggerated world, one that blended together night and day, compressed time and space, and inverted beauty and ugliness. It was a gateway to a carnival in which everything strange and meaningless could blossom. This otherworld was marvelously inlaid within the universe outside, a world sheathed within a world. Where one began, the other ended.

Regarding the theater, a wise man once penned the couplet: “Some stand aside with their hands in the sleeves / But I’ll step up and join the show.” Broadly speaking, the theater is a world; narrowly speaking, the world is no different from a theater.

In the past, theaters were called teahouses. The playbills were coarse and crude, printed with wooden planks on red paper. The writing was difficult to read, yet aesthetically pleasing. At the teahouses, most of the guests in the main hall were male, with the vast majority of the bejeweled consorts seated in the boxes, and the hoi polloi in the seats behind them. In those times, the stage was square in shape, with the nuisance of two large pillars at the front obstructing lines of sight. There was no backdrop, only a wall of boards covered in the auspicious character for happiness in red writing, or with the expression, “Blessed by the Official of Heaven.” Stage left and stage right were respectively marked “Entrance” and “Exit,” and the players were inflexibly mandated to enter and exit the stage in the appropriate direction.

In comparison, the theater experience at Great World was novel. To the Chinese middle and lower classes, repressed to the point of immobilization by bureaucrats and colonists, it promised a more fluid cultural experience. Great World maintained more than ten venues, all of which employed the newest Western stage structures, with 300-400 seats each and a total capacity of more than 4,000. The most unique aspect was the utterly original space occupied by Great World’s relatively traditional theater, formed by a ground-floor main stage and the 100 meters of bridges and corridors connecting the various adjacent multi-storied buildings. First of all, this layout formed an axis of transportation, reducing the distance between the various theaters and attractions. It provided convenient passage for Great World visitors to move between theaters and a variety of routes for them to choose from. In addition, these structures happened to create a circular stage in the style of ancient Greece, with the bridges and corridors doubling as audience space surrounding the stage. The main stage, as a performance area, magnified the ceremonious feel of taking in the show.

The teahouses of former times were like basecamps entrenched with waiters. At the major Beijing opera houses, service staff would bring hand towels and cups of hot water to those seated in the first four or five rows. Anyone hoping to see a show would be obliged to provide a few teacups of business to these waiters, and, of course, leave a tip. Great World replaced the waiter system with communal teapots. For just a copper coin, audience members could drink a cup of the tea of their choice. This modernizing modification, akin to the transition of 50 years prior from haggling to price tags at fashionable continental European department stores, allowed for a theater experience with far fewer visual and auditory distractions.

Great World was, at various times, labeled a “money squandering den,” “Money World,” “Evil World,” “whore market,” and “nest of the Four Olds.” It may seem vulgar and coarse in comparison to that rosy, gilt image of Republican Shanghai prevalent in the contemporary cultural imagination. But looking back, it is hard not to admire its prescience. In the decade that followed, this festive mode of consumption rapidly spread throughout the world, becoming the anthem of entertainment for the urban middle classes.

On August 23, 1966, the first day of Shanghai’s campaign against the Four Olds, a large contingent of Red Guards surrounded Great World. In a frenzy of shouts and screams, they pulled down the huge “Great World” signboard, and in doing so brought an end to the legend of the “The Biggest Amusement Park in the Far East.”