THE GLOBAL CONTEMPORARY: ART WORLDS AFTER 1989

| March 7, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

Major historical moments made 1989 a famous year of change: the Russian withdrawal from Afghanistan, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the violent suppression of student movements elsewhere. No wonder either that the following implosion of the Soviet bloc, the end of the Cold War and the German reunification appeared primarily as a historical victory of the West and the capitalist system. Today, more than 20 years after 1989, possible alternative readings of these events and their consequences have come into sight. For Peter Weibel, Karlsruhe’s ZKM director and curator of the exhibition “The Global Contemporary: Art Worlds after 1989” the year of change, 1989, signified “the end of Western monopolies,” not only in the general struggle for markets, but also in the global definition of power, and in which what or who is to be included or excluded. The art world is no exception: the former guiding model of “Westkunst” (Western art)— one very famous group exhibition in Cologne in 1981, curated by Kasper Koenig and Laszlo Glozer— has since been considered a discontinued model, while the booming network of biennials is cultivating its own art-genre, and the partition between the art market and art institutions has become ever more permeable. Whether in art or elsewhere, the change that takes place, according to Weibel, does not happen as Samuel P. Huntington’s much-touted “clash of civilizations” but as an ongoing process of “rewriting” previously existing rules, club affiliations, and alliances Weibel says “is creating unrest and anxiety in the West.”

Obviously, the ZKM goes uninfected by the quickly spreading fear of globalization. Rather, it is contaminated by the resultant unrest. “The Global Contemporary” is part of a multi-year research project on the future of the museum, “Global Art and the Museum,” which has resulted not only in this outsized survey exhibition, but also in numerous publications, lectures, workshops, and conferences on the issue. The self-imposed task of the show, which is well-fitted by works of over 100 artists— including Guy Ben-Ner, Luchezar Boyadjiev, Nezaket Ekici, Mona Hatoum, Elodie Pong, IRWIN / NSK, and Mladen Stilinovic— is, Weibel says, nothing less than “making it possible to depict the global practice that has changed contemporary art as radically as ‘new media’ had done previously.” Does this mean that these processes are actually reflected in the art itself in an exhibitable way? Sometimes this seems the case, for example in a work like Tangier-based artist Yto Barrada’s Tectonic (2004/2010): a sky-blue-backdropped world map made of wood, on which continental shapes in warm shades of brown are installed as if on rails, so they may move toward as well as away from each other. In other cases, such as the ten classic sheets of Martin Kippenberger’s hotel drawings from 1990, the reference to the exhibition theme is quite hard to decipher.

So, the question remains, whether one actually has to go to Karlsruhe in order to experience the future of the globalized art world. Not necessarily, as the analysis of the interaction between the post-’89 deregulation of markets, the rise of the “New Economy,” the impact of worldwide instant networking, and the emergence of entire continents on the radar of galleries, auction houses, museums, collectors, and curators is by no means cutting edge. Nearly a decade ago, Documenta 11 curator Okwui Enwezor had already criticized the Western fixation of the art world, and worked hard toward a true internationalization of the exhibition in Kassel. Those discourses around a global art have also been long institutionalized in Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures/HKW), or through organizations like the German Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations as well as the artist exchange program of the DAAD, not to mention some specialized galleries who are doing their part to foster the same conversation.

Thus, on the one hand, “The Global Contemporary” can be understood as an honorable continuation of these efforts toward a broader understanding of global art. But on the other hand, it probably serves as a publicly exhibited search operation for new meaning for a large institution, whose formative years (since 1989) were enthusiastically devoted to the media arts, which now seems a little worn. Since the emancipatory net-art activism of the 1990s has lost its utopia to the commodified reality of web-based social media, their platforms, institutions and festivals are stuck in a sense of crisis. On the occasion of this specific exhibition, the new complexity that goes along with the long farewell of the Western-centered art world seems to coincide with Peter Weibel’s careful “rewriting” of the programmatic ZKM-source code. The old love of cybernetic LED-art and techno aesthetics still flickers here and there, as in the ZKM-produced data visualization of the development of the art market and the biennials over the last two decades, or the “trading-bot-performance” titled ADM VIII (2011) in panoramic optics by Rybn.org, which remains basically as cryptic as the daily stock market barometer on television.

Seen from this angle, “The Global Contemporary” provides in two ways an experience of a departure from the idea of a canon— both the institutional and on a more general level— even if only temporarily. The old patterns of classification simply do not work. No contribution highlights this fact better than the Tehran-born, Berlin-based artist Leila Pazooki’s Moments of Glory. This installation of neon signs distills art-review prose from the internet, ultimately consisting of more than a dozen cold, flashing half-sentences. They read: “Japan’s Andy Warhol”; “African Kiefer”; “Chinese Gerhard Richter.”

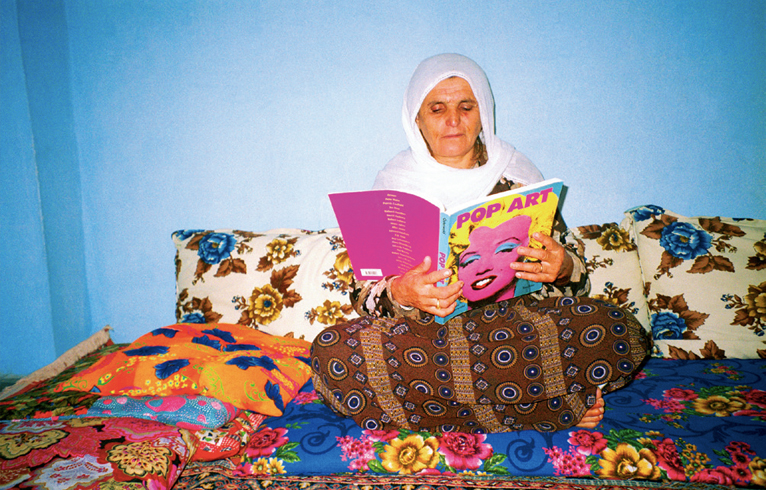

Assumedly, the criteria that led to the selection of works for “The Global Contemporary” are founded only partially in the art itself: “As one would expect, the new boom in art production is accompanied by a crisis in the Western concept of art whose limits cannot be expanded arbitrarily,” reads a statement by co-curators Hans Belting and Andrea Buddensieg in the introduction of the 100-page exhibition guide. “In fact, the globally expanded practice of art accepts the loss of a binding concept of art in order that artists can make national, cultural, and religious themes ‘public’ through the medium of art.”

More than ever, the interaction with global art demands the provision of an educational frame: “One sees only what one knows.” To what can the audience know? To what extent can they see? Walking through the huge exhibition hall of the Museum of Contemporary Art at ZKM, the assumption that little is known about global contemporary art— and its contexts— quickly becomes a certainty. For example, except for a few insiders, presumably there will be not too many people outside of China who can identify most of the personnel shown in the sprawling, seven-screen Super China! (2009) by Navin Rawanchaikul. In the style of a Bollywood movie advertising billboard, the artist, born in Thailand but now living in Japan, painted a panorama of an art scene at boiling point: among others, the major artists Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang and Zhang Huan are visible, as well as influential collectors such as Guy and Myriam Ullens or Uli Sigg. Rawanchaikul did not forget the intellectuals either: critic Li Xianting, curator Melissa Chiu, and the outgoing Ullens Center director Jérôme Sans are also present. In its colorfulness, the work also evokes the celebrated cover of the Beatles’ 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, designed by British Pop artist Peter Blake. The music behind that cover provided much of the soundtrack to the Summer of Love, the peak of the Western hippie movement. Will China’s art boom enter the history books as the stoned hippie phase in the history of the contemporary art world?

The contribution of Beijing-based artist Liu Ding is a stone on which reads the inscription: “Omission is the beginning of history writing.” On top of this, the unwritten history is to be seen, in the form of a book-object embossed in gold: “A History of Chinese Contemporary Art: 19XX to 2050.” It is no secret that this history is written increasingly in China itself and lesser and lesser by Western museums, collectors and auction houses. In this history, the Western reception of Chinese art appears as one chapter only. It is quite possible that in the near future the words from Croatian artist Mladen Stilinovic’s famous 1994 banner— also shown in the exhibition— will no longer be so self-explanatory: “AN ARTIST WHO CANNOT SPEAK ENGLISH IS NO ARTIST.” Kito Nedo