STATE OF THE MARKET 2011: AN EARLY WINTER

| April 12, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

IN ACCORDANCE WITH the auction house pattern of holding major sales in the spring and autumn, the Chinese art market saw a succession of major auctions throughout the fourth quarter of 2011. The crowded schedule spanned autumn and winter, and as the schedule progressed, the season seemed symbolic of the state of the art market, which appeared to have entered winter early. If the boom cycle of the art market is readily comparable to the four seasons, then the boom that began in 2009 reached its midsummer apex during last year’s spring auctions. Indicators such as total volume, sell-through rate, and average closing price all reached historically unprecedented highs; but come autumn, the market skipped over the gradual wane of the season straight to the endpoint of the entire cycle: winter.

SOTHEBY’S HONG KONG HINTS AT AN AUTUMN CHILL

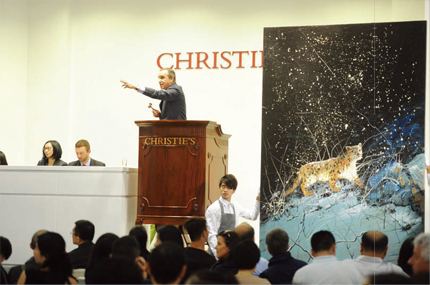

IN THE FOURTH QUARTER of 2011, Sotheby’s Hong Kong kicked off the auction season in early October, and the auction schedule reached its peak in November. China Guardian started the Beijing action in mid-November, and later that month, Christie’s Hong Kong held its second round of autumn auctions. A second round in Beijing took place in early December, led by Beijing Poly and Beijing Council. The action subsequently moved to Shanghai before concluding, at the end of the year, with Xiling’s fall auction in Hangzhou. The process was accompanied by a dramatic adjustment in market prices. Interestingly, this adjustment grew in intensity as the season progressed, culminating in a definitive demonstration of the conclusion of the art market boom period. If the entire process can be compared to the changing seasons, then the Sotheby’s Hong Kong fall auction was an autumn chill on the heels of midsummer, while the first round of fall auctions in Beijing marked a surprising cold snap, and after that, despite the last-ditch tactics of the major auction houses during the second rounds in Beijing and Hong Kong, the art market succumbed to the icy vicissitudes of winter.

As the first sign of changing weather, the Sotheby’s Hong Kong autumn auction suggested only a change of mood. The auction numbers were not particularly ugly; the overall results did not match the spring auction, but the drop was not enormous. The results in the three major categories of Chinese painting and calligraphy, ceramics and handicrafts, and modern and contemporary art were uneven. A new high was reached in Chinese calligraphy and painting, and in ceramics and handicrafts, the second sale of the Meiyintang collection outperformed the spring’s first installment in both sell-through rate and total volume. However, in contemporary art, the second sale of the renowned Ullens collection attracted market attention by vastly underperforming the first, which took place in the spring. Most of all, industry experts noted a change in mood among auction attendees and sensed that an adjustment in market prices was imminent.

A COLD SNAP SURPRISES CHINA GUARDIAN

BY THE TIME China Guardian kicked off its fall auction in mid-November, price adjustments in the above-mentioned three major categories were already in full swing. The first evening auction bore the brunt of the impact, as the “Classical Furniture from the Ming and Qing Dynasties” special showing of huanghuali and zitan furniture produced an astonishingly poor 33% sell-through rate. This result was sufficient to demonstrate that prices in the ceramics and handicrafts category had taken a turn for the worse. In the oil painting and sculpture category, China Guardian featured an impressive 3+1 lineup of “Early Oil Paintings,” “Realism,” “Contemporary Art,” and “Sculptures,” but the results were merely passable, with many notable lots left unsold. In the house’s strongest category, Chinese calligraphy and painting, Wang Hui’s Landscape Inspired by Tang Poetry broke the RMB 100 million barrier, but a relatively large proportion of lots went unsold. There was also a dramatic fall in the attention given to modern painting and calligraphy, which constituted nearly half of the total volume. Many fine artworks by perennial bellwethers Qi Baishi and Zhang Daqian also failed to sell.

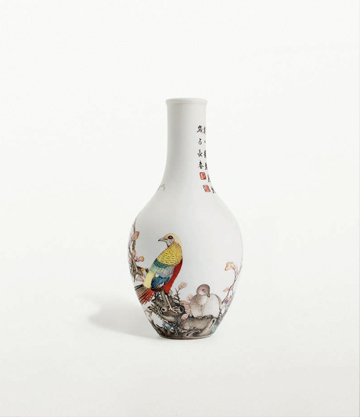

It is worth noting that the “Classical Furniture from the Ming and Qing Dynasties” special showing, which followed special showings of huanghuali furniture in spring 2011 and autumn 2010, was no coincidence. The price of antique huanghuali furniture had skyrocketed during the previous two special showings, to the point that the prices for huanghuali wood and components began to vary based on the results of China Guardian’s auctions. But in the ceramics category, signals of a price adjustment were evident early in 2011— even for Ming and Qing imperia-lkiln porcelain, the most highly prized collector’s items. At the first showing of the Meiyintang collection, which Sotheby’s Hong Kong dubbed “the auction of the century,” many high-priced lots went unsold, triggering market anxiety. Indeed, the Hong Kong market has led the way in price changes throughout this boom cycle. After payment failed to appear for the Qianlong vase sold in November 2010 by a small auction house in the London suburbs for RMB 550 million, Sotheby’s Hong Kong instituted a steep down payment of HKD 8 million for the Meiyintang showing, leading many high-priced lots to go unsold. For example, the highlight of the auction, a Qianlong cloisonné enamel vase, did not sell until a private deal was reached after the auction. Nonetheless, various major Chinese auction houses followed suit in implementing high down payment systems. This issue illustrates a problem that has long dogged the Chinese art market: major buyers fail to pay on time, endangering healthy development.

THE FIRST SNOWFALL DAMPENS POLY AND COUNCIL’S FALL AUCTIONS

IN A SYMBOLIC meteorological coincidence, Beijing’s first snowfall of the year came during its second round of auctions. Guardian was caught unaware by November’s cold snap, but Poly and Council had prepared for inclement weather by adjusting prices. LEAP learned in pre-auction interviews with Zhao Xu and Dong Guoqiang— presidents of Poly and Council, respectively— that they had both asked principal auctioneers to lower starting prices following the results of Beijing’s first round of auctions, including Guardian’s. This strategy provides one explanation for the major rebound in sell-through rates in the second round. However, the auction results indicate that the effect of price adjustments was limited. High-priced lots bore the lion’s share of the price adjustments, for as one might imagine, lower-priced premium items could trigger market attention, ultimately leading to high bids and strong results. However, for the medium-to-low-priced lots, one might lower prices to match reasonable market trends, but such low-profile items might still go unsold. After the auctions, Dong Guoqiang stated that the outcome of these price wars demonstrated a change in the direction of the art auction market, not just a technical adjustment in prices. Under the combined pressures of cold weather and adverse circumstances, the art market had entered winter early.

So what are the implications of these events? Many have quoted statistics and data, and some, such as China Guardian founder Chen Dongsheng, have forecast a 40% decline for the spring auction cycle. At the China Guardian preview event, LEAP happened upon the incognito CEO of Sotheby’s Hong Kong, Kevin Ching, who made an important observation: aside from the Meiyintang, Ullens, and other special showings of private collections, what was left to see at Sotheby’s Hong Kong auctions last year? In fact, that sort of special showing was a characteristic phenomenon of the boom cycle. The 2009 explosion in prices originated with the Ullens collection, from the record in antique painting set that spring by Song Huizong’s Rare Birds Painted from Life to that autumn’s sale of Wu Bin’s Eighteen Arhats and Zeng Gong’s Letter Leaf, which marked the beginning of the “Hundred Million RMB Era” (see LEAP 3). The combination of these extremely rare pieces from private collections— so-called “new faces” or “unfamiliar faces” in the market— with the influx of large amounts of capital into the market opened up room for price increases. These sales embodied the original purpose of auctions: determining prices for new or unfamiliar faces. However, Chinese auctions have their own unique characteristics. Many people see them as mechanisms for setting prices, as business transactions, and as speculative opportunities for rapid returns on investment. Such attitudes flood auction houses with “old faces.” Thus, the present adjustment period is actually a reversion, and not only in terms of prices. It is also a reversion in terms of direction: a reversion to the original purpose of auctions.

THE CONTEMPORARY ART MARKET PREDICAMENT

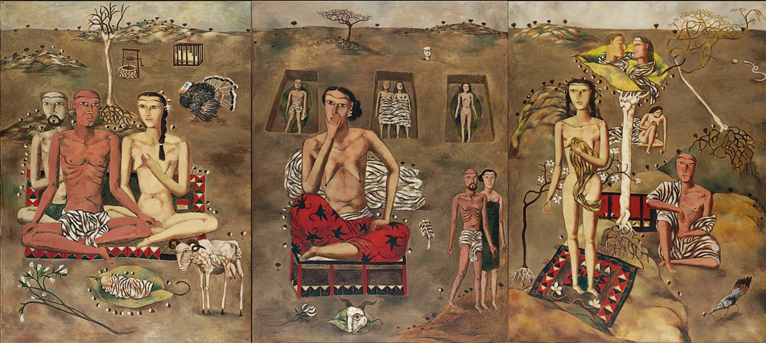

IN THE ULLENS special showing of contemporary art, the 105 lots auctioned in the spring auction earned a total of HKD 427 million, with 12 lots selling for greater than HKD 10 million; but in the second, autumn showing, the total volume only reached HKD 132 million, with only two items going for more than HKD 10 million. This massive contrast reveals how the skyrocketing prices for Chinese contemporary art over the past several years have concealed complex problems. First of all, relying primarily on auction houses to display contemporary artworks has led to an obvious market epidemic. Art forms are limited to framed paintings, and content and themes of ideological nature have received undue emphasis, manifesting the “Chinese symbolism” popular in Western art circles. These works have clearly imitated Western contemporary art in terms of both ideas and methods.

As the market for Chinese contemporary art blew up in recent years, artists became celebrities and important works became canon. This process had two phases: first, the period of celebritization, represented by the “The Big Four,” Zhang Xiaogang, Wang Guangyi, Fang Lijun, and Yue Minjun; and second, the period of canonization, during which buyers began looking beyond reputation to consider the works themselves. This phenomenon of canonization was clearly demonstrated by the spring 2011 Ullens special showing, which did not dwell on artist reputations and emphasized not only the aesthetic value of artworks, but also their historical and cultural value.

A closer look reveals that the results of the Ullens special showing also reflect the predicament presently faced by the contemporary art market. First of all, the standout artists from the first 30 years of Chinese contemporary art indeed enjoyed phases of individual accomplishment, but they have lacked staying power, and thus their sky-high price records are difficult to match. Second, mainstream forms of contemporary art over the past two decades such as installation and video art have not become mainstays of the auction scene. The art market faces a multitude of challenges, but more importantly, Chinese contemporary art is itself at a crossroads. In the present atmosphere of diversified creative endeavor, the future trajectory of Chinese contemporary art remains unclear.