WANG YUPING: “ART AND SKILL ARE INSEPARABLE”

| April 3, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

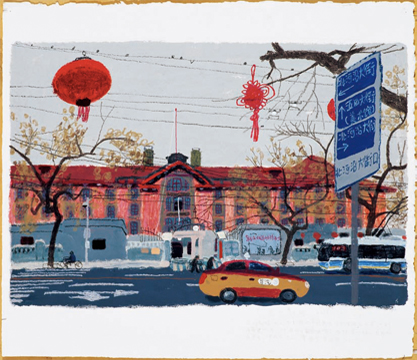

THE SUBJECTS OF my paintings are all familiar places and people, and that is because knowing them well, I feel confident in drawing them. Recently I made some small paintings on the streets of Beijing, chatting with the old men and women living in the hutongs, whose accents are so familiar to me. The scenes were ones I painted when I was young, and after all these years they have slowly settled in my heart. After gaining so many skills over the years, it is only natural that I return to paint these places. They seem to belong to both the present and the past. The main scenes I paint are in places that have not yet been ruined, those that are more or less the same as they were 20 or 30 years ago. Nonetheless, when you get to painting all those new street signs, there is no mistaking that you are in the present.

I like to take photos, but I never paint from a photograph, as I rather prefer randomly looking for something new and unusual. When I sketch, for example, a gust of wind sweeping by can affect my use of the brush—but the wind does not blow in photos. The words on my paintings are all dictated by my moods. When I am sketching, if I suddenly think of something but do not have a piece of paper at hand, and I am afraid to forget about it, I just write it down then and there, on the painting. Pastels cannot reproduce the fine Arial print of those street signs, and that is why I especially like them— they can be expressive without being polished. With too fine a brush you will linger on the details and neglect the opportunity to be raw and honest. At the very start, I used acrylic for the sake of convenience; it dries quickly, so you can start drawing what you want straight away. When I step out the door to go paint, convenient materials and methods are priority.

I do not worry anymore about what I eat or drink, or whether I paint well or poorly; I am not concerned with these things. For me, the most interesting aspect in the painting process is how you paint, and which materials you use, and why. When you scratch an itch, you scratch where it feels best. It is the feeling of working with my hands that interests me most. If you follow your desires, over time, the right skills will gradually come from your heart, and you will grow addicted to these skills.

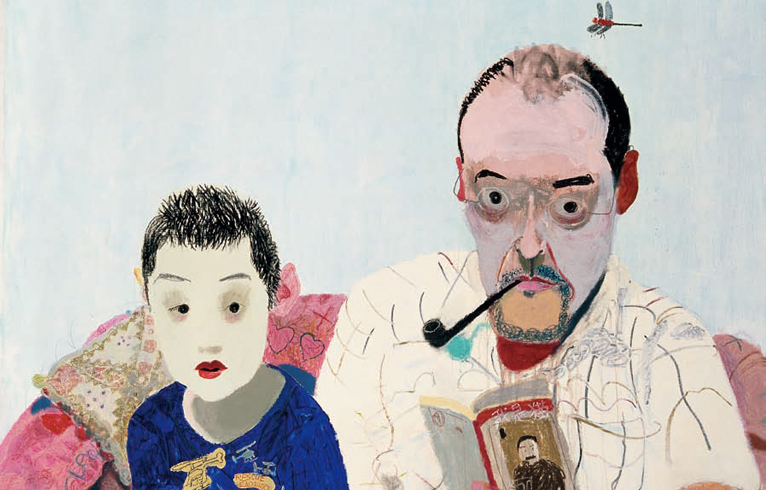

Literature has a huge influence on my drawings. Why do you like a specific author, a specific painter? Because you are part of him or her, and you can find yourself in his or her work. I gradually came to appreciate what for the moment we will call “pure skill,” by which a few individuals have also influenced me. Xin Fengxia’s book, for instance, has had the most direct influence on me. During the Cultural Revolution her legs were broken, which later left her paralyzed from the waist down; she was unable to leave the house, let alone perform. A former pingju actress, she was illiterate until she took a literacy class as an adult. Afterwards, she wrote down her life story. I have talked to a few friends about Xin Fengxia, and they believe it is her experience that has moved me, but I think this is not entirely true— I have been also fascinated by her unadorned style. She doesn’t use adjectives, thinking only about how to explain things so that others can understand. This is something she does unintentionally, but it is also something that used to be promoted by the older generation, as we can find, for example, in Ye Shengtao’s work— he referred to it as “written speech.” Ah Cheng is similar in that way— the deepest impression he made on me was his lack of attitude.

I am not too good at thinking things over. Frankly speaking, I am actually a bit against reflection. Talking this over with a friend a few days back, I told him I was a brainless person. He objected that I was wrong, that my exhibitions were a critique of thought; I replied that I had never thought of that before, and if such were true, it could only be coincidence. In art today, there is too much talk of ideas and viewpoints, but my greatest pleasure is still painting in and of itself. When we are young and we pick up the brush for the first time and we start painting, it is because we love it. But after all the years of art training, study, and reflection, it is no longer as enjoyable as before. This, I think, is a problem. Over-emphasizing innovation has become a spiritual burden, and the pleasure we felt when we held the brush for that very first time has disappeared.

I like so-called “pure skill,” but it must be positive, appropriate and relatively mature. There must be some thought behind it, but this does not need to surface. With, say, Zhuangzi’s writing, it is possible to dismiss the content, as style and form themselves reflected his attitude. Nowadays, we seriously neglect such aspects.

The reason why skills are so often misunderstood is ignorance, regardless of whether such skills concern painting or materials. Why are so many people, including those who have not undergone specialized training, making oil paintings today? I believe it is because this field has not encroached on this topic, which leads people to believe that oil painting is a breeze. But only after gaining a deep understanding of what skills are is it possible to understand the difference. Take the color red in China, for example: here it has five or six shades at most— vermilion, crimson, and so on— while the West counts about 20 kinds of red altogether, each one different from the other. In the Japanese color scheme, we can count 30 to 35 kinds. You may be a professional oil painter, but can your eye distinguish these subtle differences? This is precisely what defines people’s specialized knowledge— having “enough” or “not enough” of it, or, more simply, being specialized or not.

Today’s art has tired our eyes, leaving us nauseous and fed up to the point that it is hard to find unpretentious, sensible work. Yet I still think that art ought to work for the benefit of society. It ought to make people happy. It is necessary to criticize contemporary problems, but I believe I do not possess the insight or ability to do so. I just wish to bring some comfort to myself and other people. Once, a friend’s child came to see my exhibition, and he said, “When I saw uncle Wang’ s paintings, I thought that life was beautiful.” Everyone has a heart, and everyone’s heart has a soft spot. It is just that in order to survive in this world, many people have put on a face and stiffened their heart. “Yes” has become “No.” It is simply wearisome. (Translated by Marianna Cerini)