HE XIANGYU: THE PRIMACY OF PROCESS

| May 31, 2012 | Post In LEAP 14

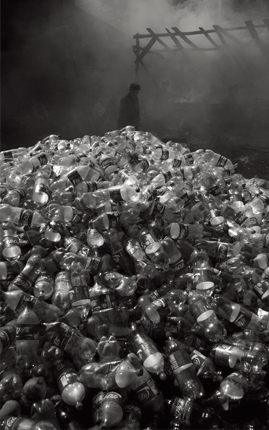

The artist He Xiangyu (born 1986) has made a quick name for himself in the contemporary art world. His reputation, for the most part, owes itself to the scale and grandeur his work has taken on, both uncommon for an artist his age. The huge, post-apocalyptic landscape mountains of black crystalline residue seen in his Cola Project (2009), created by boiling and reducing 127 tons of Coca-Cola over the course of more than one year, is a prime example of the bravado that backs his practice, as is Wu He You Zhi Xiang (2009), a 26-ton pile of dead wood reigned in the corner of Today Art Museum by a massive chain and anchor that threatened to cave in the gallery floor. However, with most of He Xiangyu’s work, the end result is secondary to the processes, both physical and psychological, that lead to its spectacular fruition.

Cola Project has been embraced by some as a critique of the invasion of Western culture into China, of the arching domination of free-market ideologies over his young generation; indeed, the seething, large-scale destruction by a Chinese artist of capitalism’s tastiest flag-bearer makes such a reading difficult to resist. The critic Gao Minglu, however, offers a more insightful analysis into He Xiangyu’s practice, marking He’s work as essentially Maximalist, or primarily dependent on the personal relationship between the artist and the material object. He’s interaction with Coca-Cola began with small-scale experimentation indoors in his Beijing studio, but eventually ballooned to transcend the individual and incorporate the public. Through an extended network of personal connections in his hometown of Dandong, Liaoning, the artist secured an entire lumber mill and employed a team of migrant workers to carry out his vision, meanwhile somehow persuading both local police and environmental authorities to turn a blind eye to his otherwise suspect activities and their daily billows of pungent, toxic smoke. In the popular parlance of Chinese contemporary art, He’s long arms transformed Cola Project into a work of social intervention, an execution of power on supra-individual scale.

Power is a curious mechanism, though. Back in Beijing, the work’s debut exhibition at Wall Art Museum was shut down after only three days, due to the opposing intervention of the muscle-bound multinational. He Xiangyu, however, couldn’t have been any more indifferent. His own intervention had already come to its initial completion, and besides, more components were and are to be exhibited abroad, including the archival empty bottles, cauldrons, smokestacks, as well as full-size human skeletons made of Chinese jade and steeped in boiling Coca-Cola and calligraphy and traditional landscape paintings rendered in Coca-Cola-based ink on indigenous Yunnanese Dongba paper— in short, an entire arsenal of aesthetic explorations comparable to the fundamental extent of the project. Like his jade skeletons, with the project’s industrial-scale implementation and the public knowledge of its happening, society had already been quietly tainted. That being said, He’s project is indefinitely unfinished; he continues to boil things in Coca-Cola in his studio from time to time, and he may even experiment with knock-off shanzhai versions of the soft drink in the future. The only thing that can bring an end to the project, all joking aside, is that most real of realities, which buttresses most of his practice: death.

This greatest of life’s mysteries is most apparent in He Xiangyu’s The Death of Marat (2011), a stunningly life-like resin sculpture of the corpse of Ai Weiwei, slyly left prone on the floor of a small German gallery for the world’s most sympathetic passerby to see through the window. A cursory glance at the installation suggests it could very well have been the work of Maurizio Cattelan, which shouldn’t come as a surprise— He Xiangyu, should he admire an artist like he does Cattelan, will do his utmost to form a relationship with that artist’s work, even traveling abroad just to see an exhibition. In terms of form and spectacle, The Death of Marat truly does evoke Cattelan’s suicide squirrel, or hanging children. He’s joke here is equally serious, but without the humor; his Ai Weiwei is the solemn appropriation not just of Ai’s visage, but of the activist attitude that circumstances in China have produced and offered to observers like He. “Ending” the life of the country’s most famous artist and airdropping his body into a small German gallery to the shock and surprise of viewers— this is not the consummation of a personal relationship with his materials, but with the process of absorbing social conditions. A simple Google search reveals also, of course, its degree of social intervention.

Death permeates much of He Xiangyu’s other work, as well. The installation Xiang (2009) saw salvaged tribal wood from the Dongba minority region of mountainous Yunnan— in the words of Gao Minglu, an “anthropological” endeavor; another critic deemed it as the “preservation” of China’s “original ecology” by the “new generation”— refit to shape full-size fur-lined coffins. The interiors of these sturdy wooden sarcophagi bore the soft allure of comfort, but collectors’ fear of bad luck left them unsold, and He is considering burying these in his hometown as a way of fully effectuating the work. For his installation and performance piece Man on the Chairs (2011), He annexed old wooden logs from a disused aqueduct in the same area and rearranged these into throne-like chairs on which dancers lithely but frenetically climbed, avoiding the ground as if it were a plague as scathing and deadly as one of He’s bubbling cauldrons of Coca-Cola. Meanwhile, the gallery’s janitor walked to and fro during the performance scrubbing the chairs, indifferent to the struggle between life and death surrounding him, either as if he were a ghost impervious to the perils of the ground below, or a simple reminder to ground the viewer in reality.

Reactions to Man on the Chairs were overwhelming rooted in the chairs themselves, or in He Xiangyu’s transfer of their indigenous function— first as living trees, then as dead wood, and finally as aqueducts crucial to the Dongba’s livelihood— to chairs, or more precisely, chairs that aren’t even meant to be sat on. An anecdote of He’s from his time in Yunnan perhaps best recapitulates his involvement with the ensuing artworks: walking home one night he was attacked by knife-wielding local thugs, and if it weren’t for the thick collar on the vintage American Air Force bomber jacket (also acquired in Yunnan, a remnant of World War II), one of their slashes would have sliced his cervical vertebrae and likely killed him. He escaped with only a small scar, and returned to Beijing to continue working.

With a slight smirk that belies how he privileges process and material interaction over result, the artist knowingly states that “nothing that isn’t allowed in China cannot not be done.” With the right connections and tactic, any source material can be acquired, and deployed however one desires. For He, no project is too intimidating, no studio too restricted. In fact, He’s aim is to eventually rid himself of studio space altogether, to mastermind his projects from the comfort of his own home, traveling as necessary to the nodes of their execution. Even now, He is in the US in order to complete a series of light-boxes titled “Mother.” The series’ medium— object-based and immediately visual-centric— and thematic preoccupation with the womb might seem a slight departure from his previous work, but they are both nonetheless suffused with the rules of power, and with our precarious proximity to death. True to form, He promises this next exhibition to be on a suitably grand scale. Exactly how this will be remains to be seen; the outcome of any process always waits until the last moment to show its face.