CHINESE ART IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION: FU BAOSHI (1904-1965)

| June 11, 2012 | Post In LEAP 14

Imagine the French Revolution hadn’t come until 1949. Suppose also that the Academy established in the late seventeenth century had continued to guide art education. Assume, in addition, that when political change finally arrived, an artist trained in these old master traditions had to suddenly adapt to a new ideological climate. Instead of depicting scenes from the Old Testament or Ovid’s Metamorphoses, like Poussin, he is now called upon to present factories, mechanized armies and contemporary politicians. How strange and incoherent this artist’s retrospective would perhaps appear. His career would be hard to understand.

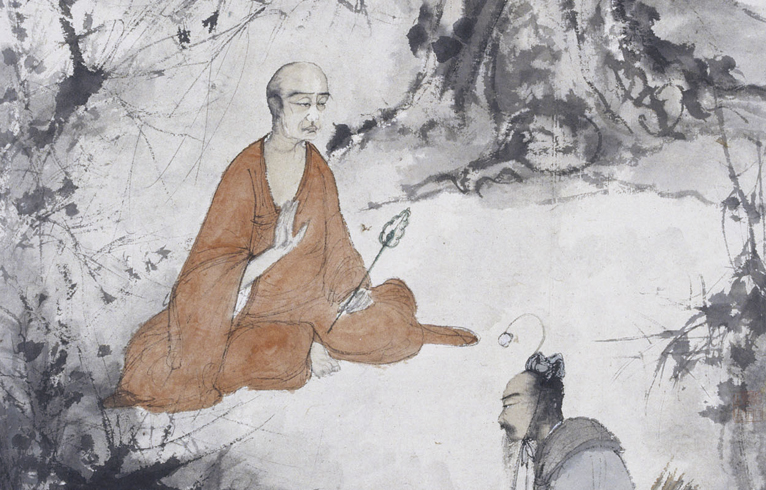

Fu Baoshi had such a career. His remarkable story, presented in this exhibition of 70 paintings and 20 seals, encompasses, almost, the history of art in China from just before the end of the old regime up to the eve of the Cultural Revolution. The earliest paintings on display, Set of Four Landscapes (1925), are scrolls that imitate such ancient masters as Mi Fu, Ni Zan, Gong Xian, and Cheng Sui, a formal path the artist would follow for his monumental Autumn Ravines and Burbling Springs: Landscape in the Style of Wang Meng (1933). In the 1930s, Fu went to Japan, where he studied Japanese histories of Asian art; in 1935 he even exhibited in Tokyo. Back in China during the Sino-Japanese war and concerned with the relationship between art and the artist’s moral character, and also with China’s national identity, he painted the even more traditional-leaning The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove (1943).

After 1949, when Fu refused to move to Taiwan, the subjects of his art changed drastically. Though a non-Communist, he had to respond to Communist directives, which proved difficult. Eventually, he developed his own methods of painterly acquiescence, melding the visual tools of the Party with his own take on traditional brushwork. Crossing the Dadu River (1951) shows a Red Army boat. On an official delegation to Czechoslovakia he painted Prague Castle (1957), showing a distinctively European motif— as ordered— but tempered with trees depicted in time-honored Chinese gongbi, while the Chinese airplanes of Irkutsk Airport (1957) sit against a foggy ink wash landscape. His Snow: Poem of Mao Zedong (1958) represents picturesque mountains described in that poem: “such is the beauty of our rivers and mountains.” In Draft of “Such Is the Beauty of our Rivers and Mountains” (1959), a sketch for the monumental painting in the Great Hall of the People made with Guan Shanyue, the world of scroll painting is left behind— in spite of the work being composed in ink and color on a paper scroll. The penultimate and likely most well-known picture in the exhibition, The First Mountain of the Long March (1965), capitulates the depth of distance of Fu’s art and compromise, showing a tiny red flag (and red-tinted sky) amidst a mountainous landscape. Fu died of a stroke later that year. The catalogue notes that, no matter how “faithful” his paintings were, had he survived, he would have been persecuted for his wartime support of the Nationalist government as well as for his views on Chinese art history.

In the accompanying catalogue, lucid essays— by Anita Chung, Kuiyi Shen, Tamaki Maeda and Aida Yuen Wong, and Julia Andrews— provide commentary that no matter how enlightening, could have dwelled more on Fu Baoshi’s research into and actual interaction with art history. In the end, however, their writings could never fully explain how Fu personally understood his own difficult situation. But then again, taking such an assumptive posture might be gratuitous— maybe only from our perspective does his attempt to preserve traditional Chinese painting appear as quixotic as it turned out to be. Whatever the perspective, Fu Baoshi remains an indelible channel for understanding the development of modernism in China, and thus, perhaps, twentieth-century art as a whole. David Carrier