TRADING FUTURES

| August 8, 2012 | Post In LEAP 15

Over Taipei Contemporary Art Center’s (TCAC) two-year pilot period, in addition to organizing exhibitions, performances, and hosting short-term residencies, the minds be- hind TCAC have curated a wide variety of lectures. Now, on the eve of its relocation, they mounted the last exhibition and conceptual interrogation to take place on TCAC’s found- ing campus. In “Trading Futures,” TCAC asks, “What is ultimately created in the process of art making?” as a point of departure for exploring the ways in which art— infixed in this massive system at the intersection of labor, social values, consumerism, and even an economy of desire, especially in the context of capitalist art exchanges— maintains its independent kinetic energy and sustains its role in reversing the situation within such a huge system. “Trading Futures,” co-curated by Meiya Cheng and Pauline J. Yao, invites artists Heman Chong, Yu-Cheng Chou, Minja Gu, Hu Xiangqian, Kao Jun-honn, Lee Kit, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Koki Tanaka, Charwei Tsai, and Xu Tan to create on-site. In so doing, the exhibition attempts to open up new worlds of possibility through a diversified spectrum of media and action.

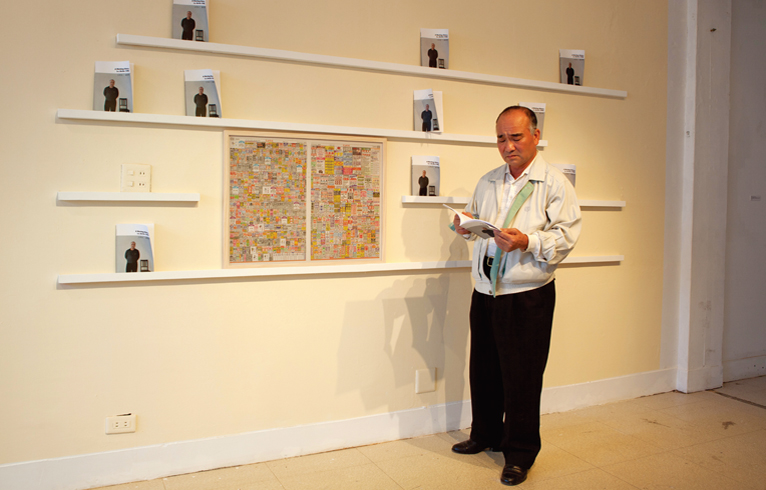

First, with Open Sesame, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu exhibit two exquisite BB guns purchased in Taipei by the artist pair and “lent” to the exhibition’s sponsors. The guns are in the “long-term care” of the sponsors, until some hopeful day in the future— one that likely will never arrive— when a legal modification permits that they be returned to the loving embrace of their owners. Heman Chong’s A Little Story About Money and Fathers (for CELR) inserts 13 Taiwanese bills, amounting to TWD 26,000 in total, into the pages of 13 different books by Chilean exile poet Roberto Bolaño, on loan from the Taipei Public Library. Somewhere in each book, one bill sits poised for chance discovery by future readers. Yu-Cheng Chou, always setting the bar in the strength of his conceptions, contributed the piece A Working History—Lu Jie-De. In compiling the up-to-date work history of a man named Lu Jie-De, Chou engages us in a discussion of the instability of contemporary society’s “odd jobs” ecology. Chou placed a want ad for a temporary worker in the newspaper and, after following up over the phone and in person with a heap of potential candidates, he selected 50-year-old Lu to act as guardian of the artwork until the end of the exhibition. Upon their arrival, visitors discover a middle-aged man quietly sitting in a corner, then organizing books on a shelf. Finally, they understand that this unassuming man is Lu Jie-De himself, the central axis of the entire piece. Koki Tanaka’s Let’s Discuss What His Future Project Should Be is a continuation of his 1988 work, again inviting a group of artists, curators, authors, and one gallery worker to talk about the direction of his work. Through recorded images in which Tanaka himself is absent, we may observe what happens on a battlefield of intellectual engagement when different personalities adopt different thought processes, viewpoints, and narrative approaches to the question at hand.

This exhibition speaks to multiple levels of meaning. Along with inquiring into the absurdity of the capital-driven art world and its myriad “transactions,” it also asks the question: for works like these— whose production is so linked to the environment they inhabit, whose conceptions are so time sensitive and so based in behavior and pure action, and whose value is so utterly impossible to “exchange”— how are we meant to collect them? Amidst an increasingly rigidified system of artistic thinking, the curators attempt to provoke and draw out other possibilities, shedding light on new models to absorb into the creative process, and reminding us that within manifold states of “transaction” hides a still wider range of sensibilities that we have yet to expose, perceive, and humanize. Wang Yunglin (Translated by Katy Pinke)