HU XIANGQIAN: A RIDICULOUS BUSINESS

| October 16, 2012 | Post In LEAP 16

THE PERFORMANCE ARTIST Hu Xiangqian (b. 1983) is quick to point out that he does not agree with that classification. More appropriate, he claims, would be “performer” or “actor.” For one, his work is rarely prepared for a live audience, and furthermore, although he readily admits to have never studied, say, Jacques Lecoq or Jerzy Grotowski, his creative method is strikingly similar to those of physical theater: “I lend my body to a story.” For his latest exhibition, “Protagonist” at Long March Space in Beijing, Hu elaborates on the bodily detachment of his “acting”: “[it is] probably an important way of being an onlooker to myself, as if I had another pair of eyes looking on me all the time from way above. It’s like being watched by another person— a viewer. But I don’t care. I do what I want on the stage of reality.” .

Hu Xiangqian’s indifference to being observed stems from the absurdity of his work— for the absurd to succeed, it inherently must not fret over appearances. In one of his earliest documented performances, I Open Certainly You Arrive the Pacific Ocean (2005), the farcical had already made itself readily apparent, as Hu attempted, from its banks, to row an entire island away from its original location (the film was shot from a boat drifting on the water to give the illusion his efforts were not so Sisyphean). The island is the home of his alma mater; this “departure” may mark his first foray into the art world, which has proven to be both a befitting stage and an audience for his trademark amalgam of antics and naiveté.

One might even go so far as to say that Hu Xiangqian has become a poster boy for Chinese contemporary performance art, a claim that if need be can be vindicated simply by way of his video stills; images of Two Men (2008), in which he and a platonic buddy dressed up as green and red traffic lights and proceeded to grind and breakdance in the middle of a pedestrian crossing, are as ubiquitous online as they are laughable. The same goes for Within One Meter (2011): a mere glance at the melodramatic expressions Hu’s face takes on as he “performs the performances” of soap opera actors— weeping over a hospital bed, arguing with a lover, or looking just plain serious— can’t not produce a chuckle in the viewer. And: aerial shots of his behind taken from Sun Tan (2009), for which he sunbathed butt-naked for six months straight, hair in dreadlocks and all, determined to “look like black people.” But all jokes aside, these and other works by Hu Xiangqian lay bare an aptitude for bodily involvement that has finally freed Chinese contemporary performance art from the shackles of violence, ritual, and political obsession. If the pioneering performance artworks in China in the 1980s and 90s were a solemn, one-way allusion to politics, then Hu Xiangqian’s use of the body is a lighthearted release from politics. (Or, perhaps, considering the multifarious contexts in which his generation has grown— in China, especially, this age of breakneck over-saturation can quickly induce a dulling of the senses— it is a distraction from politics. Hu claims to create not by channeling creativity, but by acting as a sponge: “I collect a bunch of information, like trash, and build it into something.” One idea here being, of course, that there’s plenty of trash from which to glean artsy .

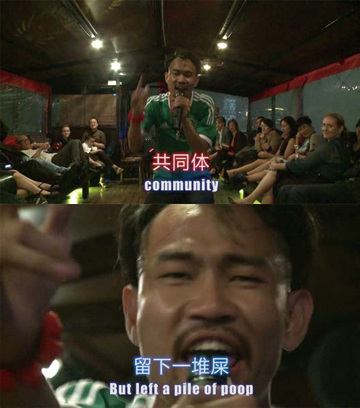

Apart from the general position Hu Xiangqian’s practice occupies in the recent art historical canon from a distance (as well as its expansion within the system), the artworks themselves possess a specific charm, one that is rooted in their foundational absurdity: the confusion of the audience. First displayed at “Protagonist,” Look Look Look (2012) amateurishly records Hu Xiangqian, bobbing and dipping like a madman to a thumping dance beat, laying down crude hip-house verses that could have been written by a facetious 12-year-old: .

I don’t need a stage

I don’t need make up

I am so brazen-faced.

No one can see through.

No one can see through.

No one can see through.

You can’t see through.

He can’t see through.

No one can see through.

Look look look Look look look Look look look Look look look

Look look look clown clown clown Look look look clown clown clown

you’re seeing a show, you said I’m seeing shit, I said

You saw who I am,

and spat to me

But you spat to a pile of poop

Your spit melts a pile of poop

Your spit melts a pile of poop which turns to community community community community

This, in the middle of Victoria Harbour during Art Hong Kong to an audience of VIP guests— presumably collectors and gallerists— mostly middle-aged and definitely less certain of how to react than their happy whoops and hollers suggest. Could the artist truly be so pure of heart, so childlike, so guileless? The question is a trap from which it is difficult to break free, and escape is anyway polar: the viewer walks away with either the firm belief that Hu’s art sits at the epitome of the unpretentious, or the firm belief that they have been duped by just another case of anything-goes. Particularly in the case of Look Look Look, the immediate reading tends towards the latter.

Nobody today will step forward and claim that institutional critique is by any means innovative technique, yet Hu Xiangqian’s approach is worth a moment of exegesis. Precisely because his deception is so seemingly guileless— a grown man who willingly makes a fool of himself (and out of tune to top it off!) is simply too likeable to ignore— dissing potential collectors right in their face becomes the very source of his marketability. Hu understands the human need for distraction— be it from the monotony of the Quotidian or from the expectations of Taste— so well that the art “community” get a kick out of their own grilling. Were the contemporary art mechanism of today analogous to entertainment at the turn of the twentieth century, Hu might very well be society’s newest favorite vaudevillian.

Hu Xiangqian’s amusing-but-biting song-and-dance rumination on the art world adopts a more polished and cinematic guise in Acting Out Artist (2012), a fourteen-minute silent film created during a subsidized stay at the lavish Swatch Art Peace Hotel in Shanghai. Opening with an extended take of what looks like a statue of an Orientalist Colonel Sanders but turns out to be Hu as the subject of a day-in-the-life-of-the-artist spoof, the scenes alternate between the diaristic, the self-infatuated, and the greasily gestural. From lazily perusing a book (haughtily: in English) under bed sheets of gratuitously high thread-count to animatedly spelling out his Art for an interested foreigner (a Chinese artist may only be legitimized by the West), Hu Xiangqian implies that he is not the only artist to assume the role of “actor.” At the same time, this smirking commentary takes a sly stab at the hypocrisy behind the lifestyle priorities and cultural identity of his young generation in general.

Being able to appreciate Hu Xiangqian’s efforts at creating art might begin with appreciating where he comes from not only as an artist, but as an individual. Hu claims to be an ardent believer in the teachings of the Indian mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (more famously known as Osho), whose views on boredom have influenced Hu since high school: “If you really want a life which has no boredom in it, drop all masks, be true. Sometimes it will be difficult, I know, but it is worth it. Be true.” As trite as they are, Osho’s words seem to resonate with the artist: constantly finding himself bored with life, he drops his mask and sets about being true. And where he is successful lies his appeal: whereas the audience may, say, dance naked in front of a mirror at home but not in public, Hu will.

For Xiangqian Museum (2010), Hu Xiangqian “mimed” out a series of artworks he had “collected” in his mind. In the ridiculous midst of iterating their complexities through the body alone, Hu’s sense of humor is readily apparent, but once its effect on the viewer wears off, a disdain for the arbitrary, less-than-inclusive museum-led system emerges, and his sincere reverence for art as an idea becomes palpable. Hu’s own description of the work: “Everyone is born to be empty. We need materials and non-materials to fill ourselves. A museum fills itself with materials, but through my eyes and my mind, a usual museum would turn into non-materials. And in my performance, these museums and artworks are represented through my body to the audience. I think the best thing about art is we can carry it wherever we go.” Through the tawdry veneer of such phrasing— especially that last sentence— one may assemble an apt evaluation of what we might call “Xiangqian Theater”: incomparably funny, densely absurd, limitlessly corporeal, and unassumingly sardonic, but genuine enough to keep the viewer nourished after laughter’s hollow echo fades away.