LIU XINYI: AGENT L

| October 30, 2012 | Post In LEAP 16

Liu Xinyi’s work is instantly recognizable from within the art environment of China today: an adeptness and integrity of the expression of form, subjects with a high degree of political sensitivity, and a (so far) clear continuity of a personal logic, with touches of obvious yet tempered slyness and dry humor. Liu’s first solo exhibition in Beijing, “Agent L,” demonstrates just how much this young artist’s maturity surpasses all expectations.

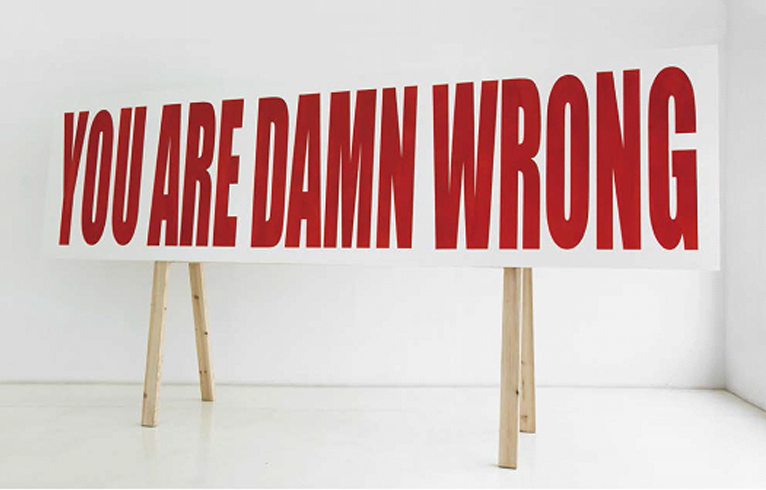

Just like the title indicates, the six works presented in “Agent L” resemble a survey of global politics from outer space. In a visual sense, this survey poses unique questions and analyzes them in a profound yet simple way, all while very insightfully bringing forth the most expedient method for finding a partial solution— an approach both cynical and naïve. The first thing that occupies the viewer’s line of vision in the gallery is also the most disturbing work, the red-on-white Universal Protest Banner, on which “YOU ARE DAMN WRONG” is written in English in boldface capital letters. This finely executed work of monumental dimensions, complete with such blatant language, takes a fairly direct and crude stance toward the visual— enough to influence subsequent views and criticism. This type of effect is indeed planned and controlled by the artist. On the floor, right near the middle of the room, is Automatic Arms, composed of rows of the waving mechanical arms of disassembled then reassembled lucky cat figurines lined up in a triangular formation; the altered direction of the arm movements made them look like gestures of protest, a group of golden, shimmering cat arms waving one after another, prodding the viewer’s limits of endurance. Clockwise on the walls are Civil Diplomacy, which with the help of spring-grip dumbbells draws nations together in a physical sense; From Marx to Mao, a collection of beards going from thick to sparse to none at all, characterizing the transformation of the international communist movement’s five most symbolic leaders; Rise of the 20th Century, utilizing the course of a plant’s development, as well as the phototactic changes in its height, to create a model of the ups and downs of the political life of the “Men of the Twentieth Century”; and The Centre of the World, taking the human buttocks as an axis onto which a slowly rotating map of the earth is projected, giving each of the countries in both hemispheres an opportunity to assume the visual significance of being at the center of the globe.

These works reflect methods for modifying visual truth: one is removing an object’s original integrity of form or context; the second is destroying or creating from scratch the standards of the real world; the third is filtering away connotations and standpoints with concrete referents; the fourth is emphasizing the disruptive existence of props and details. These methods are often employed together, sometimes straightforwardly political, other times more artistically. But the joint goal lies in making an ideal, false, “other world.” What is interesting about this is its inauthentic, excessive obviousness and sincerity. Everything with a profound, complex significance and substance is weightless here, with only the emptiness of form remaining in games and attention-seeking displays.

What “Agent L” presents at least demonstrates a creative condition where regionality and cultural divergences are superficially obliterated. Perhaps this is directly related to Liu Xinyi’s educational background, mode of thinking, or cognitive perspective on objects. It cannot simply be attributed to an individuality born out of his particular environment, but rather to the collective imprint of the generation he belongs to. Today, the experience young artists gain from continuously refining their political logic no longer overlaps with individual maturation and memory. Examining the past and the present in a rational and detached manner, they are adept at seeking out whatever leftover value is still usable.

Zhang Xiyuan (Translated by Caly Moss)