SHANGHAI BIENNALE 2012: REACTIVATION

| March 17, 2013 | Post In LEAP 18

On the opening day of the Shanghai Biennale, young artist Simon Fujiwara explained his contribution, titled Rebekka (2012), to me and another artist couple: around 20 full-body casts stationed together, occupying half of a stairway that leads into the exhibition hall. Pointing at the face of one of these clay models, he tells us that it is the cast of a girl who was involved in the 2011 London riots. Her name is Rebekka, she is 16 years old, and along with many others of her age, she was arrested and branded as “a hooligan and a criminal” by the British conservative government, for looting, stealing, and destruction during the riots. Along with the others, she faced an imminent court hearing and jail sentence. However, fortunately for her, she was asked by Fujiwara to participate in an experiment in social intervention, which replaced her trial and time behind bars with a two-week trip to China, on the condition that she was completely cut off from events in the UK, and had no contact with anyone in Britain. This experiment in intervention is analogous to the initially cheerful, and all-expenses-paid Rusticated Youth Movement; as part of the trip, Rebekka visited the Terracotta Army in Xi’an, and then a nearby factory, where, in the style of the Terracotta army soldiers, the casts which feature in this installation were produced.

Without being told the story behind this piece, we would be unlikely to discover its intention. Fujiwara told us he wanted to use travel as an educational tool, to allow Rebekka to fully reflect on British culture. This is a kind of playful expression of freedom, the individual, and society. Here Fujiwara employs a customary mode of globalized production: through travel and self-reflection from the stance of the other, artists use disparities in identity to construct new globalized landscapes, also often attempting to use forms of ceremony to “reactivate” malleable social programming.

This symptomatic approach and mode of production corresponds to the underlying tone of this Biennale. Following curator Qiu Zhijie’s hand-drawn map, this Biennale’s various locations— regardless if the converted power station by the Huangpu River, the various smaller sites scattered across the city, or the “Zhongshan Park Project”— all are put to use as a site for the construction of a temporary “heterotopia” by a large group of artists who constantly travel and produce around the world. At these sites, we have the opportunity to witness these artists, how they work and think, and how they, ac-cording to a loose objective— like the constantly re-emphasized theme of “Reactivation”— transcend individuality and form a community.

But this is not exactly a new approach. Critics of this exhibition will refer to “Magiciens De La Terre,” curated by Jean Hubert Martin in Paris in 1989, as the originator of this globalized approach to selection and display, and conclude that this exhibition has failed to break out of this now rickety framework. Furthermore, things have changed: the East-West artistic disparity on which “Magiciens De La Terre” relied has, since the end of the socio-politically tense Cold War period, somewhat disappeared. This initial shock of difference in later exhibitions (including this one) has been replaced by a completely flat, uniform style of “difference.” Despite all this, the most unfamiliar works in this Biennale are not related to black culture, queer culture, women’s rights, ethnic minorities, but those which display the still singular aesthetic experiences and social landscapes of former socialist countries. An apt example would be the exhibition “Haunted Moscow,” located downtown, which takes the legacy of East-West cultural difference and turns it into content for an entire exhibition. This exhibition at least presented two unfamiliar faces of Russia: Andrei Filippov’s installation Rolling Blackout (2012), an arrangement of unmistakeably Byzantine style flags, fans, sketches, and coats-of-arms, Filippov employing metaphor to emphasize a connection between the history of the Soviet empire and the Byzantine cultural tradition.

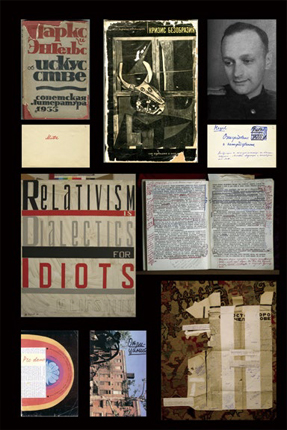

Dmitry Gutov’s special exhibition space features an array of documents which revisit the life and work of Mikhail Lifshitz, a now largely forgotten Soviet Realist. This installation cannot help but remind one of Boris Groys’ current research exhibition “After History: Alexandre Kojève as a Photographer” at OCAT in Shenzhen. Kojève— this Marxist of humanitarian spirit— was also an architect of the European Economic Community (which later became the European Union), and can certainly be seen as Groys’ solution to the bewilderment and disorder of the post-historical period. In the same way, Gutov’s method of display of these documents, drawn from the Lifshitz Institute over which he presides, can be seen as a similar effort to review, and reactivate, ideas of the past. Though it ought to be said that Russia, along with other countries of Eastern Europe, whose societies are still in the process of social change and transformation, the symptoms they are enduring and simultaneously creating and are exactly the heterogeneous landscapes which modern liberal societies, such as those of Western Europe, can barely imagine. This disparity, especially since the general crises of modern political identity, creates the possibility to urgently review, and reevaluate.

On this level, it could be said that this Biennale provides spaces in which artists of different fields, and of different perspectives, can conduct reevaluations of almost every issue. This is, of course, something of an exaggeration; when countless artists’ individual practices and different strategies are placed together on the same platform, the first thing we discover is that this community built on difference is both loose, and seemingly immobile. Not only does this supposed difference fail to challenge the collective whole. Its parts are scattered, and when placed together on this vague exhibition platform, merge together with deleterious effect. They can at best form a kind of compensatory landscape, offering the possibility of communication and understanding to different societies. But at worst, they take the form of the works presented downtown, the great earnest of archives and documents polished into slick and entirely benign promotional tools for the host city.

But if we set aside our many prejudices, this biennial does have its points of worth. At the very least, it presents something vital to contemporary reality, “Reactivation.” A patient reader need not wait long until this term becomes a buzzword in the reports of the Western mainstream media. Right now, power transitions, and adjustments of economic structure, could help “reactivate” stagnating national mechanisms. This thematic correspondence is neither accidental nor coincidental. In reality, on a far broader platform, the carriers of various crises are in need of “reactivation”: Europe on the brink of bankruptcy, America ravaged by Hurricane Sandy, Japan and its aging population reeling from nuclear disaster. And of course also that which is most in need of “reactivation”: the increasingly faltering, and depressed state of contemporary art. Pu Hong (Translated by Dominik Salter Dvorak)