KANG WANHUA: NOT INTERESTED IN ART AND NOT AN ARTIST

| 2013年05月10日 | 发表于 LEAP 19

KANG WANHUA—THIS name draws a big blank for most people in China’s contemporary art scene. From 1976 to 1979, he served as a political prisoner of the Chinese government. During those four years, he secretly painted more than 400 richly colored and vibrant works. Even though these paintings are, for the most part, only the size of a postage stamp, the intensity of the emotions they convey and the technical mastery and style recall Western Modernism. For the time, it was completely avant-garde; standing in front of his paintings makes you feel like you have fallen into some strange hole in time and space.

Kang Wanhua was born in 1944 to an average Beijing family. Since childhood he showed an interest in painting, and in 1960 he enrolled in an art school for Party cadres to study painting. In this after-school program he learned basic painting techniques and theory. Once he grew up, he was assigned to a post that was considered pretty good at the time, working in an electronics factory. Because he showed aptitude as a painter, he was later transferred to No. 179 Middle School to serve as an art instructor.

The young Kang Wanhua yearned for a free and uninhibited life. He nourished radical impulses and, drawing on influences from art and literature, gradually extrapolated them to society and reality. By this time he was already married and living away from his parents with his wife. He and a few other young people would gather together to secretly listen to music, look at catalog ues, and so on. During that time the true peak of the collectivization movement was underway in China, and if you were discovered and reported playing the guitar, you could be accused of having bourgeois tendencies—sufficient grounds for arrest and being locked up for two or three years. Consequently, Kang and his other disgruntled friends were extraordinarily cautious. They took care of every detail to avoid being seen or heard by neighbors. But Kang was reluctant to restrict himself, often casually discussing the circumstances of the time, speaking bluntly and freely about his dissatisfaction. His wife thought he was too much of a rebel, and after trying many times to persuade him to be more discreet to absolutely no avail, she eventually reported him to the authorities. Her intention was for him to receive a warning, so that he might tone down his rhetoric; she did not anticipate that the political situation was in such a critically tense period. The Ministry of Public Order carried out an investigation and an interrogation of Kang, the result of which was that they discovered that he had even once used a swath of newspaper with a likeness of Chairman Mao on it to wipe his ass. Recalling this incident, Kang says that it was purely coincidental, that at the time he had paid absolutely no attention to what was on the paper. But it made no difference. Under the circumstances, they took this kind of behavior as extreme disrespect toward the leader.

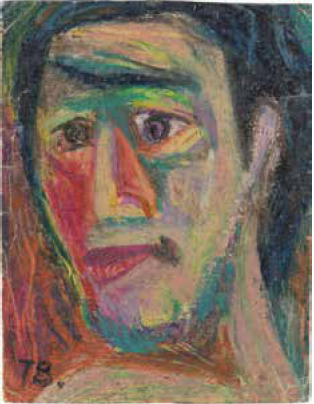

With a record of such poor behavior combined with his wife’s report, Kang Wanhua was deemed a political offender and sent to prison. During his four years of prison life, he was forced to not only undergo ideological re-education but also to do forced hard manual labor to “reform” him. But because Kang got along well with the camp’s doctors and nurses, he was able to get certification that he was sick and take almost daily “sick leave,” letting him spend time in his cell and avoid his labor duties. At that time, painter Liu Xun (who would later become chairman of the Beijing Artists’ Association and host two Stars exhibitions, all with Kang’s enthusiastic support) and other artists were Kang’s fellow inmates. At Kang’s request, visiting relatives brought him a few books and painting materials (such as oil paint and brushes). When he was bored during his hours of “sick leave,” he read and painted to kill time. Painting was forbidden in the prison, but Kang very carefully avoided detection. Playing cards, postcards, and cardboard boxes all became his canvases. These small, inconspicuous scraps of paper could easily be stuffed in the pages of books. Unable to paint from reality, most of his paintings are based on images he recalled from memory, or simply guided by imagined forms. Among his actual subjects were his prison mates. When they saw their portraits, they were amazed at how lifelike and distinct they were. Today, viewed with a contemporary eye, these little inmate portraits resemble the works of Odilon Redon and Gauguin in their symbolic quality. They are melancholy and mysterious. At the same time, they are pervaded by a diffuse and dim and yet unyielding glow.

From October 1976 to March 1979, Kang Wanhua painted more than 400 works, ranging from landscapes and portraiture and even to a few of the human form. On the whole, these paintings were mostly done with a brush and oil paint in very bright hues. Looking at them from a stylistic perspective, his painting language very nearly approximates that of Impressionism, symbolism, and brutalism, with a very mature and intensely emotive technique; his artistic influence is very pronounced. At that time in China’s history, it was really astonishing to find any artists who were capable of producing such mature Modernist works. Kang himself notes that China still had not come into contact with such works, to the extent that when such styles developed in China, they developed entirely on their own, organically. As for the bright— you might even say exaggerated— tones, these were simply the result of the artist’s unrestrained and innate preference for aggressive, vibrant colors. Talking up a great work and actually painting a great work are two different things. Those interested in romanticizing Kang’s image will be very disappointed by this kind of insipid, unsophisticated, and vulgar interpretation of his works. But as those looking at the paintings— as opposed to hearing about them— will realize, the best interpretation of the artist comes with his artworks: their masterful painterly language and the intense emotions they exude weave the artist’s life of challenges together with that period of Chinese history, which now makes Chinese people cringe to recall. There is intrinsic value in this that needs no justification.

When Kang Wanhua was released in 1979, he used three volumes of a massive tome on world history to sneak the works out of prison. After what must have felt like a lifetime, his life suddenly became remarkably ordinary. The batch of tiny paintings he had done no longer held much significance. If a friend liked one of the paintings, Kang would insist they take it. The paintings were neglected for a number of years; today Kang has only 100 or so of them to show. Most of them went to a friend surnamed Xue who took the works with him abroad. Kang later heard that this friend sold off the paintings shortly thereafter without telling him.

Being sent to prison had a profound effect on Kang’s life afterwards. Before going to prison he had already been fired from the school, and after getting out of prison his only option was to return to factory work. After 1985, in order to make some money he started a small business. Since having a stroke in 2008, walking has become difficult for him, and his hearing and listening comprehension have suffered, too. His primary focus is now on recovering.

Talking about the past, Kang Wanhua considers politics erratic. Without committing any serious crime, ordinary citizens could be punished simply for having frank discussions about current events while the corrupt authorities would sleep soundly at night. As for painting, Kang says that he is not interested in “art” and does not consider himself an artist. After getting out of prison, he rarely ever painted, viewing survival as the most important thing in life. (Translated by Caly Moss)