SURVIVORS’ POSITION

| May 22, 2013 | Post In LEAP 20

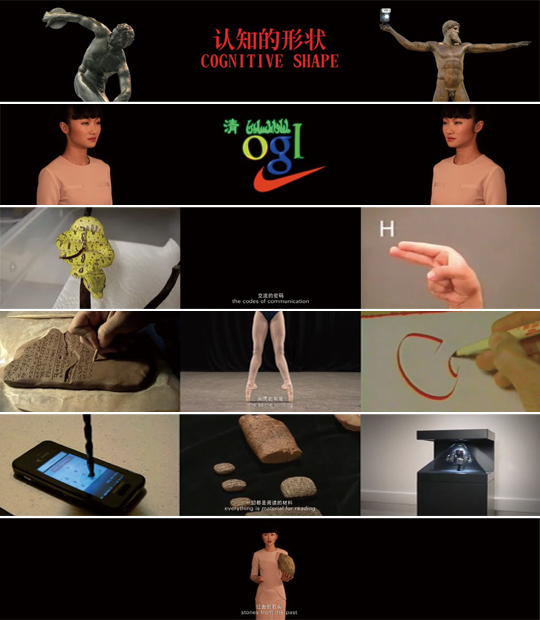

THE GUAN XIAO solo exhibition “Survivors’ Hunting” is divided into two parts to best suit the exhibition space. As one enters, one is met with deliberately manufactured chaos: installations, sculptures, and pictures with indeterminate relationships all set out together in a comparatively cramped space. Although the next space is relatively spacious, on view is only the three-channel video Cognitive Shape is no simple is no simple, on loop in the back. The position of this work in the space suggests that Cognitive Shape is no simple is intended as a key; after the viewer has watched it in its entirety, and returned once again to face those artworks and their complex relationships, suddenly everything clicks, and she is able to unravel the puzzle. In reality, this key is also a summary of the artist’s working methods and can be used to decipher the thinking behind Guan’s practice.

But Cognitive Shape is no simple is no simple, easy-to-understand exhibition guide. Its language is the language of dreams, in which images, sounds, and feelings from every kind of atmosphere and spacetime are torn open and sewn haphazardly together. The artwork’s source material has been chosen from approximately 1,000 Internet videos, movie excerpts, and images filmed by the artist herself. This huge repository of visual fragments touches upon countless fields of knowledge: archaeology, science and technology, nature, history, art, and so on. Like the presenter of a documentary, Guan Xiao herself appears onscreen to link together these segments, her somniloquous voice masking from start to finish the dense, quasi-religious electronic music and the ceaseless switching of the scenes behind her. Even if the audience can, after a cursory glance, immediately grasp the relationship between the images and this voiceover, they may still be left at a loss by the gaps and leaps in its logic. In fact, Cognitive Shape is no simple is a complete and closed system. Its structure progresses layer upon layer, its chosen material and its composition inextricably bound.

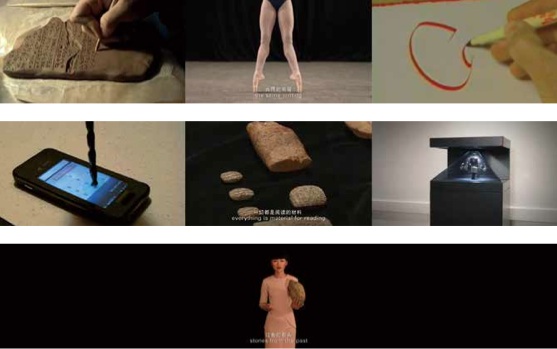

The content of this video can be interpreted in terms of the artist’s mode of viewing, as well as the influence this has on her creative methods. From the perception of an object and transformation of that object into source material, to the deep processes of personalization, this video “records” the artist’s creative “programming,” and divides itself into three parts according to this code. In the first part, ancient Greek sculptures holding electronic devices appear alongside the titles, the difference between them abundantly clear. In using this style, Guan Xiao seems to be provoking people to become aware of the processes by which they perceive these objects, an act emphasized soon after by a barrage of images. Cuneiform, English calligraphy, and ballet are shown on all three screens simultaneously, the voiceover echoing: “Collaborative writing, complete knowledge,” showing that these different forms of expression can all act as bridges, sending out a resounding or feeble signal, inciting people to approach and perceive their desire.

After this introduction, the video arrives at its main theme— how to find a needle in the boundless haystack of perceivable material, and from it, forge an artwork. In the second part, Guan Xiao creates a leading role for her “film”: “stone,” a symbol of the first material ever used to create art. The story’s plot revolves around how to regard the stone, how to use it. The narration includes lines such as: “We could make fun of it, torture it, step on it… praise it, analyze it… and of course, we could still do nothing, and let it become a way of amusing us.” This passage tries to offer a chosen principle for the accumulated mass of material and the indigestible “us”: joy is the motivating force of creation.

After this, the voiceover falls silent. The only thing remaining on the screen is a topological diagram in the shape of a tree, with stones for its roots. As the image scrolls down, a smaller leaf— that is to say, an object shaped similarly to a stone— extends into a lush branch until it exceeds the borders of the screen. This stone, and the thing it metamorphoses into, are linked together by the topological diagram, to show their inherent and common origins. Guan Xiao’s interpretation of this scene is that all sorts of forms enter her world in a tiled pattern, and she treats them all with a “fair” attitude. Through this she makes it clear that her choices are not affected by her own taste, or whether the material can represent her personality; rather, she gathers and reserves them indiscriminately.

Speaking literally, this second part seems to be contradictory from beginning to end: since “joy” is the chosen material, why are we discussing fairness? Guan Xiao might say, it is easy for the self to be moved by objects, and after this emotion has reached a certain level and we have withdrawn to examine it, we can discover their points of similarity: they are all fair. The precondition embodied in such an interpretation is Guan’s regard for art as a self-empowering territory: inside this practical territory, she has the power to circumvent an ordinary person’s cautious compliance with cognitive logic. This emphasis on fairness is made to escape subjective preference; rather, it signifies that once her selected connections are closed, she can lock up the door to the heart and view the objects simply as her own material, guarding against a yearning for them which might weaken her position as creator.

This awareness of self-empowerment is also embodied in the final part of the video. Guan Xiao has defined her work as similar to editing— “to display what has already happened in a clearer way”— and revealed how she weaves objects into her own system. For the ending of the video, she has designed a dialogue, similar to an everyday dialogue in intonation, grammar, and composition. The content, however, is completely preposterous: “language is communicated besides the shape of square,” and so on. In this way, Guan breaks away from the limitations of grammar and science with regards to “things,” reaffirming the artist’s power to deconstruct, separate and recombine materials within the creative scope.

Cognitive Shape is an outline of Guan Xiao’s declaration of her individual creative methodology. For those who work in art, an artwork’s most obvious question is universally applicable: how to avoid being buried by the visual choices and the burden of art history, to work standing firmly in one’s own position. This requires one to be succinctly aware of this position— that is to say, of the artist’s individual identity. If history is cyclical, and objects are the padding of history, then playing with outdated objects (the readymade) cannot be separated from an outdated context, and the whole thing is completely bereft of interest. Therefore, to emphasize position in an artwork is also to seek new ideas within cliché. (Translated by Sarah Stanton)