WANG GUANGYI: THING-IN-ITSELF

| May 10, 2013 | Post In LEAP 18

Roughly speaking, so-called contemporary art has existed in China for more than 30 years. Any list of its representative artists would include Wang Guangyi, who has certainly become— in his own words— “an artist of significance.” So as a retrospective of his works, “Thing-In-Itself: Utopia, Pop, and Personal Theology” must face questions such as these: what, in fact, is the significance of Wang’s work? And how can we describe and categorize its significance? These questions lead to yet another question: when did this consensus about Wang’s significance form? To put it more directly, if it were not for the reputation he established with his “Great Criticism” series, would Wang’s prior and subsequent artwork have received so much attention? The retrospective at the Today Art Museum does not place a special emphasis on the “Great Criticism” series; rather, it chronologically displays paintings from other series, showing restraint by exhibiting only three. These choices suggest that the curator deemphasized the “Great Criticism” series because the Political Pop concept has already received a great deal of market recognition. By focusing elsewhere, the exhibition leaves more room to study and discuss Wang’s art.

The retrospective’s title demonstrates curatorial diligence. These three terms— utopia, pop, and personal theology— encompass the continual revisions of ideas in Wang Guangyi’s art practice while ultimately returning the focus to the dimensions of the artist him- self. However, revising ideas does not always provide an artist with positive results. “Great Criticism” and Wang’s advocacy of “expunging zealous humanism” at the 1988 Huangshan Conference have received so much attention because of his escape from the restrictions of knowledge and the ties between art and reality. Instead, Wang directly touched and responded to the social and cultural transformations of contemporary China. In comparison, his earlier, more philosophical work, evidently influenced by the ’85 New Wave, at the very least demonstrates his sensitivity to reality. However, Wang’s art has always been situated within an immense context. Once he transforms from a provider of cultural questions to a consumer, we can see the void behind the grandeur.

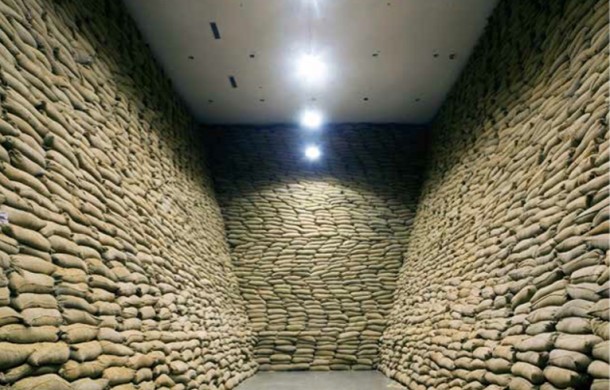

Perhaps Wang Guangyi seeks to fill that immense void with the techniques of materialism, but the transition from two-dimensional work to installation art brings with it a lexical disconnect from reality. Changing trends in the exhibition of contemporary art have also seemingly aggravated Wang’s occupational apprehensions. So although we are still seeing representations of workers, peasants, and soldiers, the change in medium yields two contradictory temporal narratives. The “Great Criticism” series seemed to prophecy imminent cultural phenomena, whereas the later installations reflect on the artist’s own historical experiences. More importantly, if theology has become a keyword in the study of Wang’s art, then does that suggest that he has completely lost the ambition to address complex cultural questions? And in its resemblance to a massive burial chamber, does Thing-In-Itself, the installation in the retrospective composed of countless bags of rice, amount to a public admission that he has reached his limits? (Translated by Daniel Nieh)