YUNG HO CHANG + FCJZ: MATERIAL-ISM

| May 10, 2013 | Post In LEAP 18

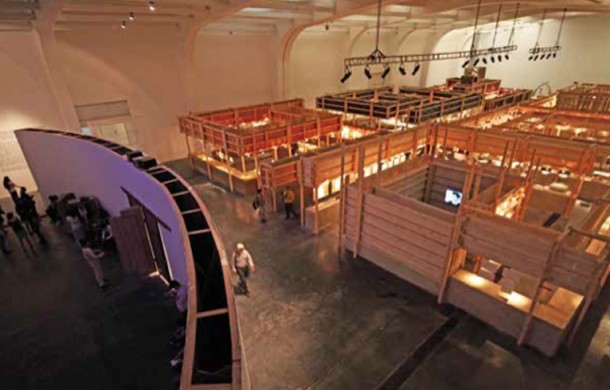

Spanning 30 years, “Material-ism” is a comprehensive retrospective of Yung Ho Chang and his architecture atelier’s body of work. The exhibition includes 6 installation modules, 40 models and 270 drawings and blueprints. The result is a full picture of Chang’s practice and explorations of architecture, culture, and art.

A majority of Yong Ho Chang’s drawings shown in the exhibition date from the 1980s, when design and drafting had not yet entered the computer age. To a contemporary eye, these meticulous and elegant hand-drawn diagrams have an air of the classical about them. The charm of these drawings not only comes from the sensibilities of their creator, but more so because they reveal the process of design and reasoning of Chang as architect: “What has been termed conceptualized thinking is essentially a means to define the question: can an object be comprehended from other perspectives? As in, to deepen one’s understanding or to extract the fundamental character of the object.”

More than a display of blueprints, the exhibition showcases a thorough examination of culture, encompassing literature, film, art installations and other areas; even within the topic of design, diverse practices such as urban landscape, architecture, interiors, products, furniture, and clothing design are all incorporated. The reason for such tremendous inclusiveness is Yong Ho Chang’s system of thought, the essence of which he once summarized as:

“Call it physicalism, materialism, or matter-ism— what is ultimately being discussed is still only a concept, or perhaps a combination of all three concepts. Because what we actually care about, as an architect or a person, is the quality of life.”

In the sense that “Material-ism” expresses Yong Ho Chang’s ideas about the “quality of life,” the exhibition responds in two dimensions. There are pieces that reveal his personal interests, such as the “architectural” kung fu film Enjoying, which can be seen after “pulling open the sliding doors,” as the signage directs the viewer. Elsewhere, in the exhibition module Saint Jerome’s Study, social critique is the driving force. Sandwiched walls seduce the viewers, who experience pangs of hunger each time they return. Its design and the resultant sensation together form a metaphor, reminding us that during years of material abundance, what we lose are spirituality and culture; the emptiness inside swells like bubbles.

Of course, when it comes to Yung Ho Chang, people pay the most attention to his designs. The overall design of the exhibition has six installation modules, perfectly embodying the design principles of FCJZ and Chang. It is in itself a piece of installation art that surprises and delights with its subtlety. The ingenious design of the individual modules is at once full of rationality and clarity, while cleverly integrating the items displayed. The materials are commonplace, such as concrete, rubber tubing, and aluminum piping; their combination highlights the variant soft and hard textures. Walking throughout the gallery, the viewer experiences courtyards, preliminary building structures, material research and remaking, and finely calibrated alterations of space. Walls turn out not to be walls, corridors not corridors, and courtyards not courtyards; the habitual definitions of architectural boundaries do not exist, yet they can be clearly felt. The elements to which FCJZ pays the most attention— space, subtlety, and scale— are found throughout the exhibition.

In 1960s China, materialism was an abstract system of thought. Now, in the materially abundant twenty-first century, is there a place for this particular “-ism?” In a time of spiritual confusion, does the meta-cultural attitude of “Material-ism” give us directions for a way out? Perhaps more precisely, it is an exhibition of Yong Ho Chang’s awareness of both a need for public engagement and for a return to the self. (Translated by JiaJing Liu)