IDENTITY ISSUES: THE FIFTH GENERATION OF OVERSEAS CHINESE ARTISTS

| January 13, 2014 | Post In LEAP 24

2012, Perspex, metal, Flexolan, 100 x 40 cm

According to historian Philip A. Kuhn, China’s “modern” emigration began in the early sixteenth century, the start of what he labels as the four eras of Chinese emigration: the early colonial age (sixteenth to mid-nineteenth century); the age of mass migration (mid-nineteenth century to around 1930); the age of the Asian revolution (late nineteenth to late twentieth century) and the age of globalization (the twentieth century onward). As far as the emigration of Chinese artists is concerned, art critic Fei Dawei tells us that from 1887— when Li Tiefu left to study at the British Arlington School of Fine Arts—through the 1940s, over 300 young Chinese artists went abroad. After the founding of New China, there were five waves of emigration: the first, just after 1949, is represented by painters like Zao Wou-ki and Wu Guanzhong; the next wave took place in the mid-1980s as Reform and Opening intensified and Western art surged into the country. Fine art was en vogue, and certain artists interested in Western Modernism once again left home. Among these artists were Yuan Yunsheng, Luo Zhongli, Chen Danqing, Chen Yifei, and Zhou Chunya; post-2000, countless artists have left China to study, and though the achievements of this current group haven’t quite grabbed the attention that their predecessors have, in a cultural context marked by simultaneous globalization and localization they are still very much worth watching.

“Local Futures: The Culture China • Young Overseas Invitational Exhibition,” which opened September 16 at He Xiangning Art Museum in Shenzhen, can be said to be the first domestic exhibition in recent years to focus on young overseas Chinese artists. The exhibition looks at and presents the works of 22 young overseas Chinese artists based in 13 different countries. Some of the artists received their foundational educations at home, leaving later to pursue advanced studies and ultimately settling down abroad. Some are the second generation of overseas Chinese immigrant families. For centuries, overseas Chinese have found that “home” rests somewhere between a “spatial community” and a “temporal community.” A “spatial community” refers to the experience of “living together,” but does not necessarily imply living in the same physical location. A person may feel he “belongs” (emotionally or economically) to a place, regardless of whether he lives tens of thousands of miles away from it. On the contrary, “living apart” is actually more likely to refer to one family living under one roof, while each member lives his or her own entirely separate life. These two types of communities are not unique to the Chinese household, but are nonetheless most evident in China, particularly with regard to families who find themselves in the midst of emigration. Feng Boyi, curator of the exhibition, emphasizes the fact that the identity of each overseas Chinese artist is unique. Here is a creative group that contains within it both pronounced difference and collective identity. The artists engage in creation of visual art at the collision and fusion of various cultural contexts, and it is difficult for them to occupy any kind of central, easily identifiable position. Because of this they have been marginalized. The intention of this exhibition arises out of the desire to penetrate beyond the concept of “identity,” and to explore these artists’ contributions as artists in their own right.

The work of the Indonesian second-generation overseas Chinese artist Tintin Wulia is conspicuously positioned at the entrance to the exhibition. Titled Invasion, the installation features a cluster of flowerpots sitting on the ground, each filled with red sand, anchoring a red thread. These threads appear to connect at their other ends to flying kites. It turns out, however, that this connection is intercepted—at the window leading to the other side of the exhibition wall where the kites reside—by a magnetic strip and a sharp razor blade, floating mid-air. Each flowerpot-and-kite pair in fact involves two threads: a pot anchoring one thread, a kite holding up another thread, the two ends of the threads brought precariously together by the delicate magnetic connection between the strip and blade, thereby forming what looks like one continuous thread from pot to kite. The kites do not fly freely, but are rather suspended from hooks in the ceiling. They can only struggle to look upwards in the futile hope of some day flying. These kites are made from photocopies of the artist’s family’s citizenship documents—including her grandparents’ papers, which date from before the founding of Indonesia and indicate that she is indeed a Chinese descendant. These documents are an attempt to draw upon two completely opposed emotional experiences: on the one hand implying the intimate connection the artist has with her ancestors, on the other hand invoking the sensation of a kind of exclusion. For her own introduction to the work, Wulia uses fluent English. Indonesia does not encourage the dissemination of Chinese culture, and so her family used only English, even at home. To this day she cannot speak a word of Chinese. “Sometimes I become confused about how to find my cultural roots. I don’t believe that the world can be arbitrarily divided into ‘East’ and ‘West.’”

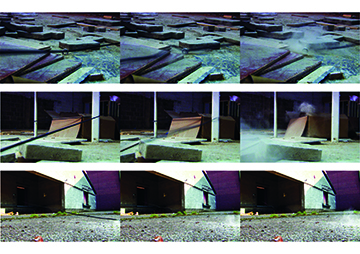

2010, single-channel projection, loop, 58 sec.

Liu Qianyi, who studied abroad in Japan, embodies another classic example of this sort of tension. Because of cultural difference, the people around her maintained a perceptible distance: “It was like we were constantly separated by a thin sheet of glass.” Extremely lonely, she hid away in her room creating, a state of isolation which ultimately engendered a shift in her artistic practice. Incidentally, her film The Piping of Heaven explores the conflicted inner life of a post-80s young woman. The I Ching plate in the film symbolizes the destiny of heaven and earth. When ultimately the girl breaks her own I Ching plate, she is freeing herself from “destiny.” This moment actually provides a window into the artist’s own creative trajectory: “My foundation was laid in China, but the moment I really broke out was in Japan.” To the artist’s surprise, there has been a huge difference in the responses of Chinese and Japanese audiences. Because her works deal with topics that relate to sex, the Japanese audience has expressed the impression that China’s post-80s generation is surprisingly liberated, while the Chinese audience has surmised that the artist is heavily influenced by Japanese culture.

The tendency towards a kind of “indie” sensibility has been evident at all of the numerous young artist exhibitions this year, in a trend that has manifested itself mostly through a quality of delicateness, personalization, and depoliticization in artists’ works. Even when artists do appeal to matters of politics or identity, there is still an attendant softness to it. Similarly exploring a Chinese relationship with Japanese neighbors, Ishu Han, a young overseas Chinese artist from Japan, gives us the work Neighbor (winner of the exhibition’s “Prominent New Artist” award). The piece simulates a child’s toy game, presenting two toy tanks connected by a gun barrel. They struggle against, restrict, and exhaust one another. The piece symbolizes the conflicted yet interdependent relationship between neighboring countries who, on the one hand cannot separate from each other and on the other, cannot dance together. Considering the idea this problem presents, judge Fei Dawei comments, “In this new century, overseas Chinese artists have basically grown up as products of Western education; they don’t think too much about the problem of cultural dialogue, and in their works one will be hard-pressed to find many indicators of nationality in general; rather, most of these artists are expressing personal viewpoints. They have already formed a new kind of cultural phenomenon, ‘Student Abroad Art’ [sic]. This exhibition can be understood as an example of this phenomenon.”

Meanwhile, as a participating artist, Gao Jié believes that to place the question of cultural identity on the shoulders of these “young international artists” is to use a language much too direct. The choice to employ obvious signposts will, in turn, directly obliterate any other possible perspectives from which the work can be interpreted. Moreover, explicit signification such as this will impede viewers’ access to deeper, more nuanced readings of what they see, making it difficult for them to truly experience the thoughts and ideas at the core of what the artists have created. Obvious indicators of cultural identity often interfere with a meaningful engagement with the work itself.