CREATIVE LICENSE: DEGREES FOR ART

| February 21, 2015 | Post In LEAP 30

TRANSLATION / Xi Winkler

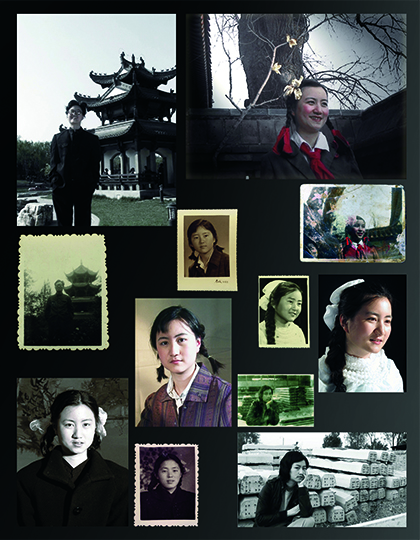

THE LABEL OF “experimental” art has developed new meanings in China since its formulation in the 1990s. In an academic context, the term means something very specific, more quantitative than political—rather than a radical split from the institution, emphasis is placed on interdisciplinary ways of working and thinking. Beijing-based artist Ye Funa, now Assistant Professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), once belonged to the first BA class of the department in which she now teaches—Experimental Art, which will soon become its own separate academy. While not as focused on theory as many art programs outside of China, the department’s postgraduate degrees (MA, MFA, and PhD) focus more on ideas than technique and do not require students to work in a single medium. When prompted to define the word “experimental,” Ye hesitates: “I think ‘Experimental Art’ as a category is China-specific. Outside of China I don’t think people call art ‘experimental’—they just call it ‘art.’ We call it Experimental Art because there’s still so much traditional art here. In actuality it’s just contemporary art.” Ye’s final project at Central Saint Martins, Family Album II (2012), analyzes modern Chinese history as represented by old family photographs, which she reenacts and syncs with recordings of interviews with the characters in each scene. Exhibited as an installation with moving image and sound, digital frames that mimic still photographs become performative.

Despite the gap between theory and technique, the Chinese MFA, a relatively recent development, has not evolved in a vacuum. Worldwide, the MFA is required for a career in art education, and demonstrates a desire to pursue more focused, independent work. However, there are still major difference between Chinese and western MFAs: within the past few decades, especially in the United States, the MFA has come to serve a more practical purpose. Although it is no guarantee of gallery representation or extensive recognition, it can still serve as a powerful networking tool, providing incentive to apply for practical reasons. In China, however, artists with MFAs are in the minority (most, however, have BFAs). This can be attributed to the fact that, in China, it is easier for a young artist to succeed on experience alone; this makes the MFA less crucial.

One major criticism of the recent surge in MFA programs is that young artists find it more difficult to think through ideas outside of the art school bubble. Those enthusiastic about the change believe that MFA students tend to have a better sense of their practices and stronger overall grasps of theoretical movements. On the other end of the spectrum, many see MFA programs, which don’t usually provide funding, as an exacerbation of social privilege, as well as an insular environment where many students’ instincts are to illustrate theory rather than merge technique with meaning. Critics Dave Hickey and Jerry Saltz are vehemently opposed to MFAs for artists with no intention of teaching. As Saltz sees it, current MFA students, who he dubs “Generation Blank,” are trapped in a never-ending cycle of self-referentiality, “[safely] rehashing received ideas about received ideas.”(1)

The youngest generation of Chinese artists, born after 1980, is mostly self-taught in what could be considered experimental (or contemporary) art, allowing them to largely escape the burden of theory. Almost all have graduated from art programs, and a small number also have MFAs. However, even though experimental art departments are now an option, most young artists tend to choose a specialization (often painting), delving into other materials and theoretical approaches on their own after graduation. He Xiangyu, Guo Hongwei, and Zhao Zhao, all three of whom thrive in the art world, received BFAs in painting but no longer prioritize any single medium. Unlike earlier generations of artists, however, they have not abandoned painting, but rather find ways to redefine it.

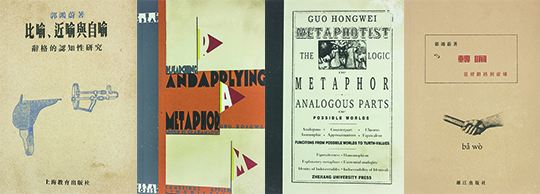

By including non-figurative painting within his site-specific installation practice, He Xiangyu shifts the emphasis from the optical space of the frame to the relationship between object, space, and viewer. Simultaneously philosophical and socially aware, these cerebral installations address both perceptual concerns and the ramifications of consumer culture. Zhao Zhao makes use of oil painting but creates a dissonance between academic references and provocative or ambiguous subject matter. In fact, Zhao has no identifiable style; rather, the pluralism of his work challenges art historical genres and cultural ideologies. Guo Hongwei’s hyper-realistic watercolors feel taxonomic, marking a desire to classify something beyond the rational. In addition to these watercolors, Guo’s practice encompasses video, sculpture, bookbinding, and mapmaking, all of which contemplate the poetics of objects. Beyond questions of medium, these artists demonstrate a certain vitality in their work, a creative impulse that has little to do with formal training.

One manifestation of the increasing bond between contemporary art and academia is the controversial PhD in art practice. Although the degree itself differs from country to country and institution to institution, it serves as an option for those who move between art and knowledge production. Most PhDs in fine art emphasize practice-led research, an ambiguous term that refers not only to written theory; rather, an artist’s practice itself can function as research. In the United States, art practice PhDs are usually offered in conjunction with other departments, such as art history or film studies. Such programs, like Transart Institute’s low-residency Creative Practice PhD program and the University of California San Diego’s Art Practice concentration, see the distinction between theory and practice as an artificial boundary. Writing may not necessarily be practice, and practice may not necessarily be writing—writing can be part of one’s practice, or even the practice itself.

This ongoing discourse of “artistic knowledge” and “artistic research” is rarely ever mentioned in China, however, which has a much more recent tradition of art practice PhDs. These concepts are not far from artist Lü Shengzhong’s version of experimental practice. As founder of CAFA’s Experimental Art Department, Lü’s intention was to provide a space encompassing conceptual art and unconventional media that could create dialogue between art academies and the public. Although the department does have a PhD program, its few students are more interested in remaining within the academic system than navigating the art world. Research and writing are a major component of the PhD, but they need not have a direct relationship with the student’s practice.

While experimental art departments draw on western MFA programs, contemporary art education in China is evolving on its own terms. Part of the reason such a gap exists between what goes on in the art world and art academies is that art degrees are still standardized all the way down to the application process, which adheres to the Chinese gaokao, or national entrance exam. This pedagogical model raises broader questions: as art becomes increasingly conceptual and philosophical, will artistic training be even more distanced from technique and skill? Will writing come to play a larger role? We are moving towards a contemporary ideal in which the artist is a critic and philosopher expected to seamlessly bridge the diminishing gap between theory and practice. As art is put into words, visual language becomes written and vice versa, opening the door to something truly experimental.

(1)Jerry Saltz, “Generation Blank,” New 1 York Magazine. June 19, 2011.