ALCOHOLISM

| June 15, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

In Asia, alcohol is the great equalizer—it turns everyone pink, regardless of race or ethnic origin. Christopher Doyle has grasped this truism, drinking copious volumes of the magical elixir to cross over. His porcelain essence shatters to reveal a beautiful pink angel, crowned with a plume of frizzled fluff.

He has Away with Words. His intoxicated aura has always been intoxicating, winning him the trust of directors Edward Yang and, later, Wong Kar-Wai. Among the glitz and grime of 1990s Hong Kong, he penetrated the crown colony’s deepest, darkest corners, beer goggles lasering through the scope of his trusty 35 mm camera. SteadiCam aims the tottering man’s vision true, the dance of weight and anchor recalling his time at sea, except this time the sea is only a beautiful metaphor (as are those expired Del Monte pineapples from Circle K).

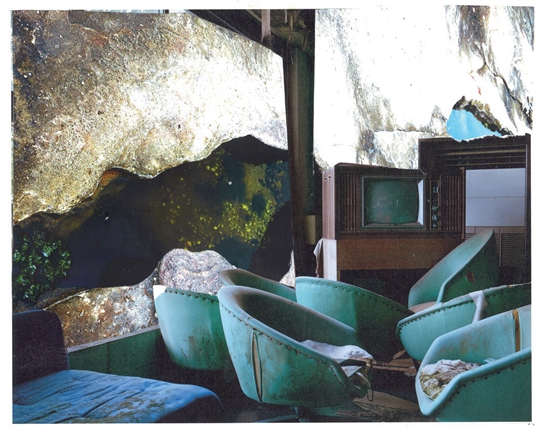

Shooting a new image-time Asian fantasia, the camera strapped to his liver distills the strange and beautiful convergence of Cantonese entrepreneurial innovation and bastardized borrowings from the mighty west, serving up the aural-visual equivalent of Hong Kong’s venerable cha chaan teng diners (incidentally, an ideal setting for the inebriated to complement the poison in their stomachs with Spam and instant noodles).

No seedy corner or local spot is safe from being seductively aestheticized into a narrative of urban existentialism and ennui for educated global consumption. A sauced up flâneur in the aesthetic-purchase-value candy store that was Hong Kong, he operates like Kerouac on ketamine.

Cinephiles rush in for their piece of the theoretical pie, living vicariously in the dream he helped prepare, while media-literate 20-somethings start to stage their romantic lives among the emotional scaffolding left by his work with Wong Kar-Wai and company. The products his alcohol-laced toil on the edge of polite society have produced even launder tenured academic careers, helping white-bearded liberals on the Upper West Side buy new granite kitchen countertops. Stirred not Shaken, everyone is In The Mood for Doyle.

A gweilo on the end credit roll, “Like the Wind” (as his Chinese name reads) held no Hong Kong identity card when his Anglo-Saxon name was first filled in on police reports for public disturbance somewhere near the 7-11 in Lan Kwai Fong. Doyle’s Ashes of Time travels well. Like the Heineken he quotes as a primary vocational influence, he is a globally trusted brand. A refugee from white supremacy before the west was lost, his endless self-destruction helps fuel the great last gasp of Hong Kong cinema.