ANGRY BIRDS

| June 16, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

It is a special time, that moment when a pop culture phenomenon becomes utterly exhausted, having sold out and merchandised itself to passé status, but then bubbles back to the surface in a new, irreverent afterlife. No longer #trending, like the plastic rings of a six-pack washing up on some idyllic shore, it can become disruptive to everyday life once again, this time for the reflection (and probably embarrassment) it occasions regarding fad-based existence and disposability in our age of cultural overproduction. While Angry Birds may now be an institution in its own right, spinning off to include 12 games and a motion picture deal, it has moved far from the popular mania its release occasioned back in 2010. Previously, you couldn’t go to any public space in China without seeing a cross-section of humans proudly donning Angry Birds merch, but now you’d need an eagle-eye to spot just one specimen.

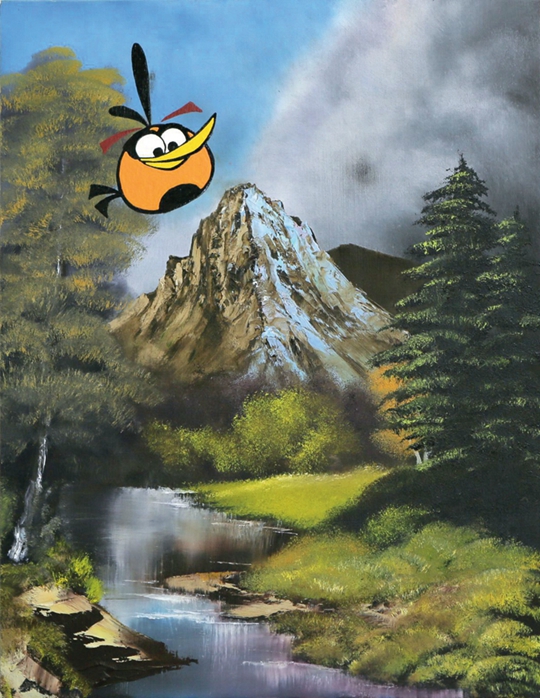

Rachel Lord’s “Angry Birds Paintings” nods to the game-turned-franchise’s status as cultural wallpaper, pairing it seamlessly with the kind of landscape painting readily available in junk stores the world over. Exploding/exploiting cheap iconography in her painting, she generates “value” by brazenly appropriating a trend-based commercial franchise and pairing it with something that is supposed to be timeless, a natural landscape. Of course, this dialogue is further complicated by the fact that amateurmade, picturesque naturalistic painting is largely viewed as the most provincial art form imaginable. It is probably still more ubiquitous than Angry Birds, and certainly more reviled by art world tastemakers.

Lord’s “put-an-angry-bird-on-it” ethos is tied to post-internet art’s relentless appropriation of mainstream symbols salient in popular consciousness, that body of everyday commercial iconography propped up by unavoidable media exposure and lavish PR and advertising spending. Her previous works exude this same impulse to target-market kitsch, like Val Kilmer Art (a rented moving truck that prowled Art Basel Miami Beach in 2012, filled with found paintings and readymades mixed among original works by the artist, all intended to appeal to the Hollywood actor’s [questionable] tastes) and “Conceptual Credit Card Paintings” (self-explanatory). This gesture vaunts the gap between the hyper-aware, media-literate young artists of this generation, whose aesthetic reference points are generally all things commercial, and those locked in an increasingly closed-off postmodern art world of celebrity, patronage, and exchange value.

This lopsided struggle is perhaps best indicated in Lord’s “Angry Birds Paintings for Stefan Simchowitz.” Unable to bring herself to sell four commissioned paintings to the film producer and collector at the loss-leading price of USD 100 apiece when he wouldn’t even drive 20 minutes to see them at her studio, Lord instead sent him pictures of two paintings of featureless eggs floating in blankness. As Lord finds out, if you put an Angry Bird on it, they will come, but they may be cheaper than your iconography.