ROOMBA

| July 21, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

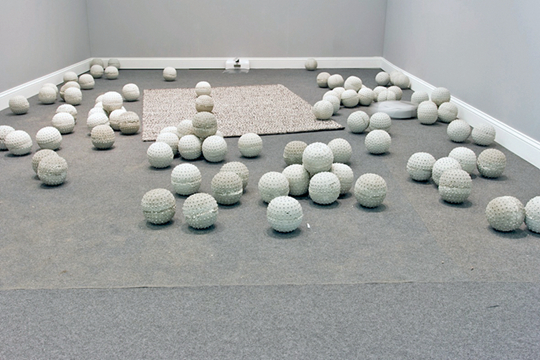

American technology company iRobot launched its cleaning robot, the Roomba, in 2002; by 2012, more than ten million units had been sold, and the brand name has become a synonym for similar robots. Owners don’t expect their Roombas to develop emotional relationships with human beings like The Bicentennial Man, but their artificial intelligence does differentiate them from normal household appliances. The Roomba is more than a tool; it’s an extension and optimization of an otherwise human function. In a way, it helps resolve a family role and gender role conflict rooted in the twentieth century. In the future, household cleaning may be handed over entirely to this family member equipped with 360-degree infrared sensors to detect dirt and map optimal cleaning routes. The flat, circular robot, 33 centimeters in diameter, is cute enough that it is never linked to the nightmarish robots of the uncanny valley; its level of intelligence rivals that of household pets to the point that a quick internet search yields plenty of photos of the Roomba interacting with kittens, puppies, and even children—it carries so many characteristics of a pet that many owners actually name them. Its ability to recognize spaces—to understand negative space in a sculpture, or the relationship between a painting and its frame—makes it a potential tool in the studio. Reena Spaulings, an identity assumed by a group of artists including Emily Sundblad, uses the Roomba to create paintings from the “Later Seascapes” series (2015). The robot’s movement on canvas leaves marks that it then attempts to clean up, further exacerbating the problem. The resulting pieces, in abstract forms and bright hues, derive their palettes from J.M.W. Turner’s later paintings, in which bright colors represent natural light. Hong Kong artist Nadim Abbas, in his piece Zone I (2014), shows the Roomba’s powerlessness against spherical concrete sculptures adorned with spikes—larger-than-life incarnations of the shape of dust—in an extension of his interest in mechanical optical recognition systems, and the hazy border between the domestic environment and consumerism.

Text by Venus Lau

Translated by Frank Qian