BLUE LIP BLACK WITCH-CUNT: Juliana Huxtable

| 2016年08月24日

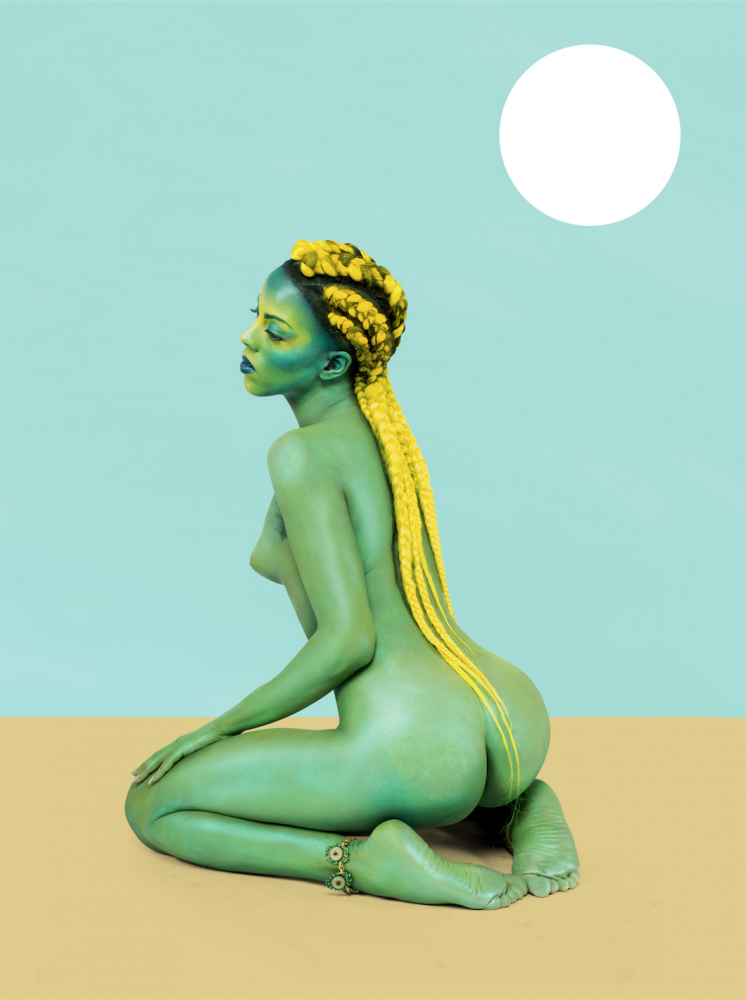

To invoke the notion of the muse around Juliana Huxtable seems out of fashion. After all, the title was tirelessly anointed to the 28-year-old artist, poet, and DJ as she gradually emerged from various sites across New York’s cultural landscape. The most recent case-in-point: the 2015 New Museum Triennial, in which the audience was confronted with Juliana, a life-size sculpture of Huxtable’s naked body by Frank Benson, exhibited alongside Huxtable’s own poetry and photographic portraiture. Media sensationalism sugarcoated her with the muse appellation and infected almost all of the popular websites and magazines.

As I brought up her muse status during an interview, Huxtable rolled her eyes. “It makes my skin boil.” To Huxtable, the muse stands for a disempowered position; between muse and maker, she has always opted for the later. In 2012, Huxtable quit her job as a legal assistant at the American Civil Liberties Union, largely due to the transphobia and liberal racism she experienced at her work environment during her transition. Already a frequent party host and promoter at the time, she decided to tear up her image as the “pretty girl at the party” by picking up DJing and launching her “nightlife gender project” #SHOCKVALUE, which soon became the city’s queer coven. Often dismissed as irrelevant or vain by cultural elites, the history of clubs and dance music is essentially an alternate history closely tied to marginalized communities, especially queer people of color. From New York disco in the 1970s through ballroom culture in the 1990s to the contentious genre of queer rap that has arisen in the last few years; and from Klaus Nomi and Leigh Bowery to Vaginal Davis, queers have always employed music and style—which Huxtable prefers to think of in terms of “the intelligence of dressing”—to establish communal bonds. Beyond tequila-infused jouissance, what Huxtable creates with #SHOCKVALUE is a safe space for those negated by the predominant structure of white male supremacy as well as the now heavily gentrified mainstream queer community that—consisting mostly of gays and lesbians with their assimilationist politics—takes pain to erase what being queer once signified. Echoing José Esteban Muñoz, the late Cuban-American scholar of performance studies, Huxtable calls together through her nightlife undertakings an alternate community that contains “concrete possibilities,” where queer people with powerful visions of alternate worlds and utopia conjure queer aesthetics to map “future social relations.”[1]

Beyond its sexist and disempowered nature, the muse—a source of inspiration and true knowledge—embodies a pre-platonic ideality that stands at odds with Huxtable’s endeavor. Huxtable experiments with a variety of mediums in her work and often mixes and matches them at will: she sometimes mixes recordings of her own poetry readings into DJ sets, and creates photographic portraits that contain rich references to black art history as well as playful representations of femininity and queerness. This formal fluidity, and the hybridity of issues her work addresses, are in accordance with a larger project that aims to subvert the doctrine of authenticity and essentialism, or any fixed notion of one’s condition of becoming.

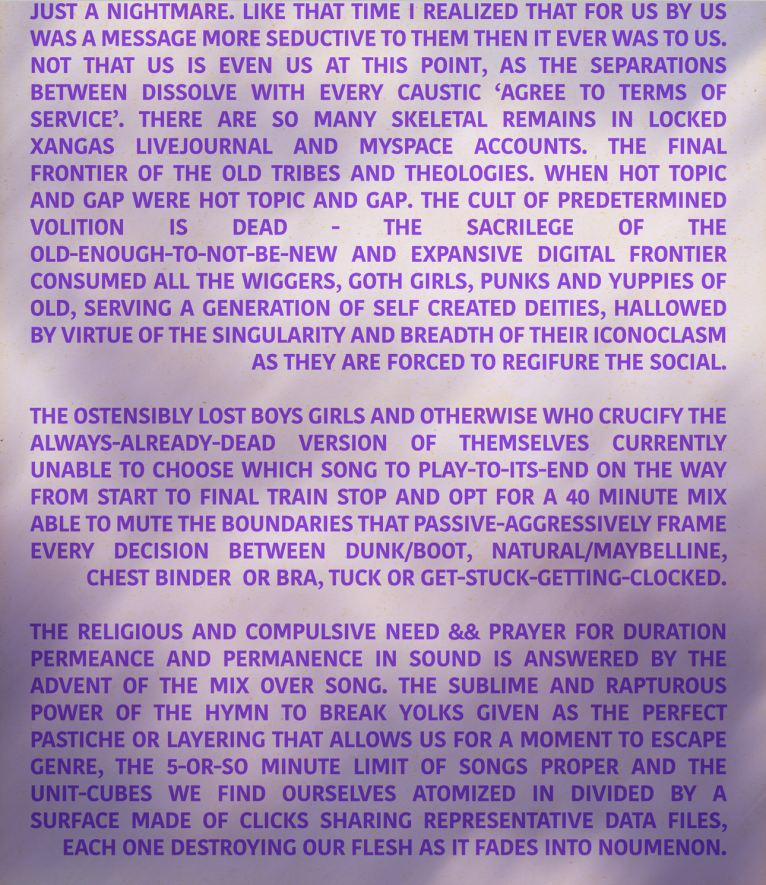

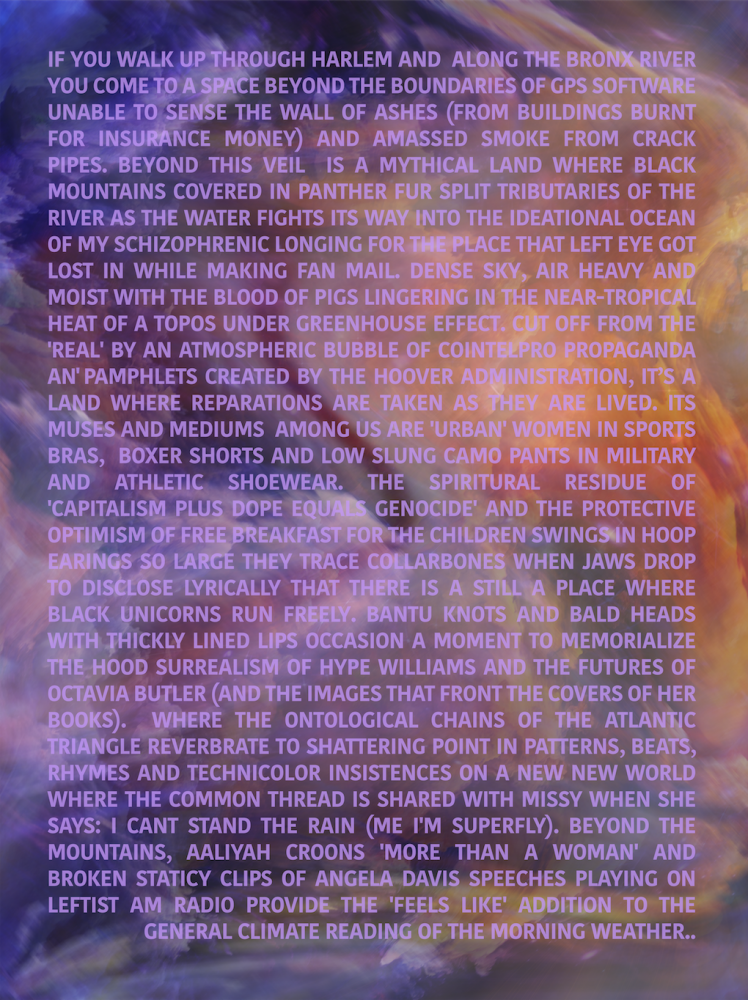

This is most evident in Huxtable’s writing, which she considers her first medium. With an evocative use of language, her poetry and short stories evoke quotidian events mixed with imagined scenes that contain her vision of futurity and challenge our imagined boundaries. In her manifesto-like Untitled—Destroying Flesh from the series “UNIVERSAL CROP TOPS FOR ALL THE SELF-CANONIZED SAINTS OF BECOMING,” she writes about the “ostensibly lost boys girls and otherwise” who pick a 40-minute mixtape over the old-fashioned single. To Huxtable, the increasing popularity of the mixtape has brought forth a new way of relating to music that challenges the fixedness of a single track. In her poem, this aesthetic attitude turns into an elliptically liberatory metaphor, hinting at the possibilities of shunning dichotomized conceptual frameworks that limit our negotiation of identities.

So, why the muse, especially when Huxtable’s rich array of creative outputs demand critical engagement? A simple yet relevant explanation is that the iconography of the muse has escaped its origin in Greek mythology and become primarily informed by circulating images of supermodels and socialites of it-girl status in our heavily image-based culture. Under this light, Huxtable’s involvement in both fashion and nightlife, as well as her active participation in image production through social media platforms such as Instagram, make her muse status hardly surprising.

However, considering Huxtable’s condition—that she “exists at the crux of almost every type of intersectionality”—and the media’s increasing attention to trans bodies (think Hari Nef, Caitlyn Jenner, and Andreja Pejic), one cannot help but speculate if a certain fetishistic mechanism is at work behind the popular relishing of her museness.[2] In an essay on Huxtable’s performance There’re Certain Facts That Cannot be Disputed, which debuted at MoMA in November, 2015, Adrienne Edwards writes, “The fetish is a perception, a manufactured projection of extreme otherness, which, rather than subsume an image or object, is a profound negation of it.”[3] Looking back at her press clippings, in which Huxtable-as-muse barely seems to refer to a specific person, the fetishistic, exploitative, and commodifying nature of this current becomes evident.

In a recent interview about There’re Certain Facts That Cannot be Disputed, which explores the possibilities of a post-identity politics, Huxtable made the remark that “the problem [with identity] is the way identity is spoken about and has historically been approached.”[4] She goes on to claim that, “I am basically just using that medium [of identity] and hopefully can get to a place where i can explode it, because I don’t believe in an identity politics, really.”[5] This invites us to question the causality of the relationship between our culture’s obsession with identity and the popular conception of her museness. What to do before a future where no existential condition is considered a lack, and therefore no identity category has to asserted? Let’s revisit Huxtable’s Tumblr. Although she no longer updates it much, her self-proclaimed motto “BLUE LIP BLACK WITCH-CUNT” still hangs in capital letters.

Anything but muse.

1.José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, New York University Press: 2009, p.1

2.Kimberly Drew, quoted in Antwuan Sargent, “Artist Juliana Huxtable’s Bold, Defiant Vision,” Vice. Online.

3.Adrienne Edwards, “Relishing the Minor: Juliana Huxtable’s Kewt Aesthetics,” PERFORMA. Online.

4.Juliana Huxtable in conversation with Andy Li, “On Healing and Self-Determination,” Bluestockings. Online.

5.Ibid.