On “Trade Markings”: Frontiers As Interfaces, Imaginaries With Responsibilities And Response-abilities

| July 13, 2018

View of “Frontier Imaginaries: Trade Markings,” 2018, Van Abbemuseum, Nederland. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

Imagine you are a falcon, perching on the arm of your master falconer, eyes covered by a hood, in a gallery of a contemporary art museum called Van Abbemuseum. You are being watched by a group of people, although you cannot see them, you can smell them. Your master signals you to perform the “feather play” that your ancestors, coming from Sub-Saharan Africa to Northern Europe via ecological migration route, have done to their European feudal lords, and you obey. Your master also talks about you as a bird-species-hunting partner-commodity being traded in Valkenswaard, Eindhoven, the center of modern European falconry trade, and being trained in the method from the Middle East. (You start to question the ontology of yourself but, at the same time, you feel kind of proud since you are actually living in the centre (TRADE CENTRE!), rather than the periphery (a small town in South Netherlands), and you are the embodiment of globality!) You suddenly have a flashback of the moment when entering the soulless gallery. Eyes open, you find that there is another you there — an embalmed and inanimate one, sitting on the arm of the rigid and uncanny wax figure of Frans van den Heuvel (in the 18th century), the falconer who served in different European royal courts, in his home setting, with his equally rigid and uncanny English wife. You cannot care less with these lifeless lookalikes, although another rich falconer Richard Hamond who left his land and fortune to Jan van Best, the one who started a cigar-making factory in 1865. Your sharp nose picks up the hardly discernible smell of tobacco from the cellar of this museum, which strengthened by the demonstration of cigar rolling in the museum and would take place just before you came in — the founder of the museum Henri Jacob van Abbe earned his fortune by opening a cigar factory in 1900, using tobacco, introduced and planted by VOC (Dutch East Indies) in the then colonies in Indonesian Archipelago. (You smile that you are in a space manifesting another kind of trade globality, related to the colonialism).

Karrabing Film Collective, The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds, 2018, film installation. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

Karrabing Film Collective, The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds, 2018, film installation. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

Karrabing Film Collective, The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds (video still), 2018. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

Karrabing Film Collective, The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds (video still), 2018. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

In your past life, you were an indigenous woman in Australia’s Mandorah, Northern Territory, who has already passed away and become a spirit. Then, you appear in Karrabing Film Collective’s new film The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds (2018). When your offspring, Aiden, who was taken away as a baby and became part of the medical experiment to save the white race, now released and traveled with his father and brother in your land, you become angry because they have never visited you before and, moreover, they allowed Aiden to be kidnapped by the white people as a “saviour”. So you murmur to your sister: “punish them!” But suddenly you are horrified by the smoke and fire near you. “Fracking!” as one of them yells. You are raged by this brutal and greedy act which harms the land and your peace. From the eyes of Aiden, you see a highly colourful advertisement of Monsanto — a chemical giant that monopolises and homogenises the agriculture, and at the same time intoxicates the land, while claiming to provide more sustainable and better innovations for the farm. You feel disgusted by this capitalist hypocrisy, but you can only haunt a person, not a huge company. You really don’t know what you can do in order to keep the land away from the industrial toxicity. Yet your thought is interrupted by the narrations by Aiden whom encountered with a mermaid in the water nearby your land, and you come to your senses that perhaps your offspring can still do something in the mirror world.

Karrabing Film Collective with the falconers and the falcon in front of Karrabing’s film installation The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds (2018). Photo: Marcel de Buck. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

Karrabing Film Collective with the falconers and the falcon in front of Karrabing’s film installation The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds (2018). Photo: Marcel de Buck. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

The above is an animist and incarnated/incarnating imagination conjuring up a beginning of the voyage in the frontiers in the 5th edition of “Frontier Imaginaries”— Trade Markings. The falconer performed during the opening and the Karrabing Film Collective has developed a new multi-screen work The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds (2018) inspired by their research visit to the Valkerij en Sigarenmakerij (Falconry and Cigar-makers) Museum in Valkenswaard. Here, the falcon and mermaids, coming from different trajectories of globality and trade, meet each other.

View of “Frontier Imaginaries: Trade Markings,” 2018, Van Abbemuseum, Nederland. Photo: Marcel de Buck. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

View of “Frontier Imaginaries: Trade Markings,” 2018, Van Abbemuseum, Nederland. Photo: Marcel de Buck. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

The frontiers in the project are interfaces between racial-political violence and massacres, colonialism and its phantoms, and dispossession and dispossesiveness along with the border disputes of nation-states, geopolitical horizons, visions of future, global migration, industrial toxicity, labor flow and congregation, space for resistance and resignification… The imaginaries of frontiers are the aesthetic captures of images that “wherein what has been coming together in a flash with the now to form a constellation”[1]. As the curator Vivian Ziherl has written in the introduction of the first edition of “Frontier Imaginaries” in 2016, “as aesthetic work, ‘Frontier Imaginaries’ pursues forms in a sense that resolutely encompasses socio-economic and historically located constellations”[2]. This means that the project does not try representing the conflicts and problematics of frontiers in Brisbane (Australia), Jerusalem (Palestine), Eindhoven (Netherlands), but rather, re-charting the undercurrents of histories and socio-economy of these places beyond the translocal aesthetic engagement with a sense of responsibility. In the interview, Ziherl returned to the beginning of the project in Brisbane from where she was:

In fact, it’s a challenge that was quite overwhelming. There was a very profound sense of accountability that if what I’ve been thinking and working on that didn’t matter in Brisbane, then it didn’t matter at all. There’s a profound sense of accountability to the place that knows me best and to the place, which I’m indebted to in some ways. Eventually it required something more than just a showcase or exhibition, something that would be able to put work internationally from Brisbane into dialogues that is in a way both serious and productive. That’s what triggered it to become a foundation rather than just a survey of what’s hot.[3]

Gordon Hookey, Murriland!, 2018. Photo: Marcel de Buck. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

Gordon Hookey, Murriland!, 2018. Photo: Marcel de Buck. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

Brisbane is the capital of Queensland, a place first inhabited by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It first encountered with European in 1606 when the Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon landed. Since the first establishment of colonisation in Australia by Britain in 1788, thousands of indigenous people were killed by European settlers in the frontier wars and yet the massacre scholarship emerged late till the last 15 years [4]. On 5th July 2017, the University of Newcastle released an online digital map that documents more than 150 Aboriginal frontier massacres in a spectrum of 80 years across Eastern Australia (1788-1872) [5]. Notably, this research project is titled “Colonial Frontier Massacres in Eastern Australia 1788-1872”. More than 65,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were killed in the massacres and conflicts between 1788 and 1930 in Queensland alone [6]. One could imagine how the term “frontier” was highly politically charged for Ziherl to start within Brisbane. That was probably one of the reasons why she commissioned Gordon Hookey for his ongoing 10-meter long painting Murriland! (2016-).

Gordon Hookey working on his painting, 2018. Photo courtesy of Marcel de Buck.

Gordon Hookey working on his painting, 2018. Photo courtesy of Marcel de Buck.

When he visited Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, Hookey was inspired by Tshibumba’s painting series History of Zaire (1973-74), which consists of 100 paintings with a narration of the atrocity and struggles in the colonial histories of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is shown in the exhibition. In response to these, Hookey, an artist who belongs to the Waanyi people, uses both aboriginal and non-aboriginal visual languages with symbolism, and intentionally misused and broke English to depict the occupations of land, massacres of aboriginal people, racism, de-humanisation, and phallic assaults against the black people and other colonial atrocities in Australia. Not by coincidence, when pointing to “Map 1.2 Some Massacres on the Frontier—North Queensland”, the artist told me that he was going to paint spots at which these massacres had taken place on his canvas as splashes of blood. Importantly, his de-colonial use of language is very powerful. For instance, in the timeline he painted on top of the canvas, NO. 11 presents perpetrators & perpetuators of Terra Nullius, he wrote:

1771 the intelligentsia braintrust of the almighty british umpire (u is crossed out and a red “e” is placed on top), congregate, corroborate, copulate, consummate, constipate, castrate and ate cook’s report to do sums.

By using the word “brain trust”, he refers to the economic and propertied aspect of legitimisation in the colonialism by those intelligentsia; by misspelling ‘empire” as “umpire”, he criticises the British Empire’s acting as a supreme arbitrator that endorsed and justified the atrocities; the rhymed verbs signify a colonial intellectual deliberation that leads to a bodily sexual violence against the colonised (such as copulate and castrate).

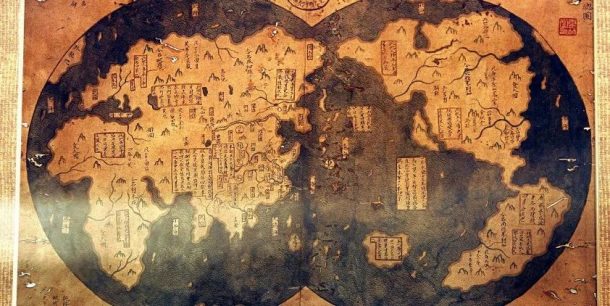

Inside page of 1421: The Year China Discovered the World

Inside page of 1421: The Year China Discovered the World

Apart from that, interestingly, there are two Chinese men in the newer part of the canvas. The artist showed me a book that he referred to — 1421: The Year China Discovered the World and told me that according to this book, the ancient Chinese emperor, Zhu Di, who sent the great treasure fleets of the Ming dynasty in the 15th century with a captain, Zheng He, who is a famed eunuch discovered Australia even before British Captain, James Cook did in the 17th century. Although some of the historians doubt the credibility of this claim, this voyage still could be imagined as the least colonial and most civilised one, compared to the Europeans’. The person who stands next to the Ming Emperor is Bruce Lee, though he is an iconic Chinese face in global pop culture, he had never been to Australia. In this anachronistic companionship, those two Chinese men are drinking CORDIAL with the aboriginal people, and a mixed-blood woman fathered by the coloniser. This somehow romanticised and utopian imaginary is activated to confront the colonial barbarism, yet one might need to notice that although the Middle Kingdom did not colonise in its maritime voyages, it does not mean that it is inculpable in this regard.

Ho Rui An, Dash, 2016 – present, lecture and video installation, car seats, synchronized screens.

Ho Rui An, Dash, 2016 – present, lecture and video installation, car seats, synchronized screens.

Compared to Hookey’s poignant critique of land occupying during the colonialism and the violence on the colonial frontier in Australia, Ho Rui An takes another path as he discovers an interesting link between trade colonialism and governmentality in Singapore. In his cinélecture and video installation DASH (2016-), he elaborates on the horizon of a dash camera in the crash of a speeding Ferrari driven by an affluent Chinese investor, who fused with a finance-capital machine, “the embodiment of speed” called by Rui An, into a taxi that symbolised the working class. The contingency and uncertainty that looks out from the dashboard resemble those of the future, which leads Rui An to probe into Singapore’s future-governmentality and governing the futurity and its peculiar connection with Shell: horizon scanning project in Singapore draws on the futurology and big data as a way of predicting crises and managing future (including using the imagery metaphors of animals like “black swan” to signify future crises), and this is learned from Shell’s scenario planning which tries to envision not only the energy future but also THE future. The frontier here is the moving vision-scape that projects (in its manifold senses, mainly a. To cause (an image) to appear on a surface by the controlled direction of light; b. to convey an impression to an audience or to others; c. to form a plan or intention for; d. to calculate, estimate, or predict (something in the future), based on present data or trends) the future onto/into the present in a vision of preventing uncertainty that will hamper the manageability of speed-flow of capitals.

His new installation for the exhibition Bukom-bukom (2018), unveils the “myth” of the birth of Royal Dutch Shell — on an island southwest of the mainland Singapore Palau Bukom (bukom is a type of seashell), and the Asiatic Petroleum Company was merged with the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company in 1907 into Royal Dutch Shell. It extracted and refined oil in the Netherlands East Indies, nowadays Indonesia, and made it one of the largest companies in the colonial economy [7]. Rui An told me that in Malay, to make a word plural is to repeat it, thus the title of the work is “Bukom-bukom”.

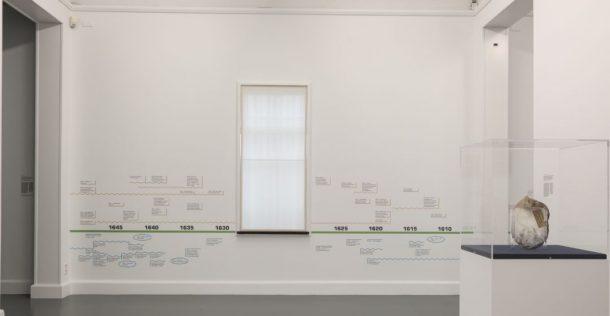

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Vivian Ziherl, and Julie Peeters, Symphony of Liberalisms (detail), 2018.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Vivian Ziherl, and Julie Peeters, Symphony of Liberalisms (detail), 2018.

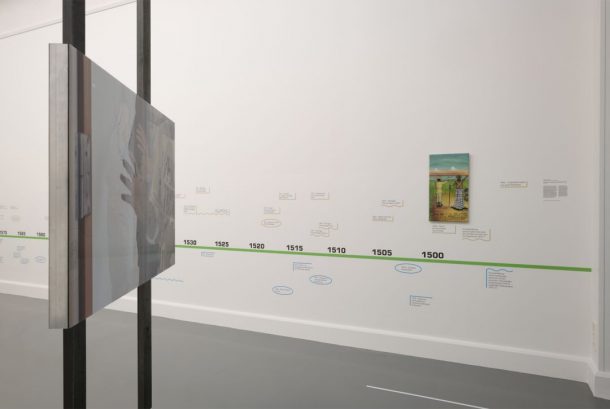

Imagine the waves lapping against Bukom-bukom from 1907 till now and towards the future, and that really merges with the waves of 500-year timeline-tideline Symphony of Liberalisms (Eindhoven) (2018) by Elizabeth A. Povinelli with Vivian Ziherl and Julie Peeters. A green timeline penetrates into the whole exhibition, with its tideline of the local histories in blue shown under it, and global histories in brown shown above it. Compared to the previous editions, this time, the Symphony is much longer and it is not only of the late liberalism, but also of the liberalism from the 1500s till 2020. It is a visual-textual “music score” that imagines histories which stanzas and re-stanzas chime, intertwine and confront with each other in their sonorities and rhythms. Ziherl points out in the interview:

So much Dutch global presence in the 1500s and 1600s. There’s no ways to pull these things apart. One of the main argument of the show is that the Netherlands has always been a global entity. [8]

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Vivian Ziherl, and Julie Peeters, Symphony of Liberalisms (detail), 2018.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Vivian Ziherl, and Julie Peeters, Symphony of Liberalisms (detail), 2018.

For instance, around the spot of 1620, there’s a writing of “1618—Willem Janszoon maps the west coast of Australia, ‘New-Holland’,” “1619— Jan Pietersz Coen conquers Jakarta, renamed Batavia, VOC (Dutch East India Company)-headquarter” above, and above 1625 is “1623/24—Chinese defeats Dutch, Penghu-island”. One could tell that the Netherlands has played a prominent role in trade-propertisation-colonialism and capitalist global relationships. The frontier here, in this case, becomes a space where the imaginaries can be responsible to the histories and the place by singing the unheard or forgotten sounds and by responding to the place in concern, such as Eindhoven, North Brabant, and the Netherlands. In this case, areas with different globalities attracted technology companies such as Philips and ASML in North Brabant that hire people from all around the world such as South Asia and sell their products globally; the aforementioned tobacco and falconry industry at the same region; the Dutch companies such as VOC and Shell that have influenced profoundly by the global geopolitics and economies. The frontier is also a space in which imaginaries instigates audience’s response-ability and their abilities to respond. The whole Symphony is presented only in Dutch, which addresses linguistically to the local audiences. Some of the other works in the exhibition such as North Brabant Temporary Hip Hop Archive shows the cultural production of Eindhoven and North Brabant as well as their remarkable roles in the development of hip-hop and graffiti art in Western Europe in the 1980s and 1990s, with which the local audience might be familiar.

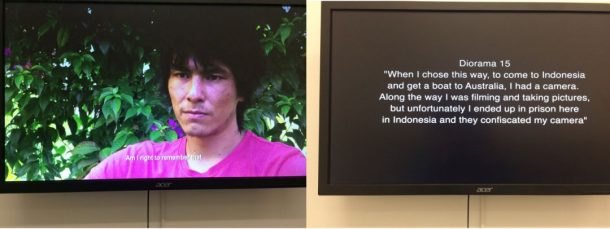

Tom Nicholson, I Was Born In Indonesia (detail), 2017.

Tom Nicholson, I Was Born In Indonesia (detail), 2017.

Apart from the connection of linguistic and culture with the audience, another way of stimulating response-ability is through employing the politics of affect. Tom Nicholson’s I Was Born In Indonesia (2017) is “based on a series of diorama figures that depict 18 episodes from the lives of a group of Hazara refugees (from Afghanistan and Pakistan) who are stranded in West Java on account of Australia’s aggressive deterrence policy towards refugees—a policy much praised by European far-right parties such as the Dutch PVV”[9].

In one of the videos, the refugee said: “I became a refugee in Indonesia when I was four. So I was born in Indonesia.” He is also a filmmaker who films the refugees around him and renders their lives visible and audible [10]. With a calm complexion, he narrated one of his films about his classmates who died in a bombing attack. With the same complexion, he told another story that he attempted to get into Australia from Indonesia but failed, his camera was confiscated, and the record of this part of refugee history was visually confiscated (diorama 15). This is one of the white dioramic figures on the wooden structure, which is ghostly white and not painted as those shown in the National Museum of Indonesia. The recognition of their existence is ghostly suspended — they are visible and invisible at the same time. On a quiet afternoon, when I was looking more closely at these dioramas, an audience who was watching the video of the refugee filmmaker sobbed. As Brian Massumi contends:

To affect and to be affected is to be in encounter, and to be in encounter is to have already ventured forth. Adventure: far from being enclosed in the interiority of a subject, affect concerns an immediate participation in the events of the world. It is about intensities of experience. What is politics made of, if not adventures of encounter? What are encounters, if not adventures of relation?[11]

In the adventure of encounter between this audience and the refugee filmmaker/narrator, she opened herself to the dioramic narrations and the imageries of a subject constrained by national borders. However, as he still strived to chart the frontier of subjecthood unbounded with the citizenship, she, by being intersubjective with the narrator and by embodying the frontier momentarily, responded to the intensity of the experience in her tears. The artwork activates the politics of affect and invites audiences to take the response-ability of the history in suspension, of the events of the world.

To conclude, the markings in Trade Markings are an artistic and aesthetic cartography of frontiers as interfaces of global socio-economic relationships shaped by trades as well as the cartography of exchange modes as the focus of understanding and critique of world history [12] considered by Kōjin Karatani. These frontiers are critically investigated and presented in their complexity, and these aesthetic forms refuse to subjugate to existing and dominant apparatus of the sensible. It exemplifies what Ziherl raised as a frontier formalism: “frontier formalism is strongly invested in aesthetic tactics of representation through rebellious images; images that chafe against existing arrangements and that posit undeniable demands for another shape and sound of the global symphony” [13]. Theses rebellious frontier images and imaginaries are generated by the responsibilities. It engages the places in their global-local contexts in order to probe into the aesthetics-politics of the concept “frontier” in actu, and to mark the frontiers of things that matter (yet they might have been shadowed and muffled by Capital-Nation-State). These frontier images and imageries invite audiences to respond to the global symphony, and relate to the stanzas and re-stanzas of their concerns, and challenge their own aesthetical-political imaginations of the frontier.

View of “Frontier Imaginaries: Trade Markings,” 2018, Van Abbemuseum, Nederland. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

View of “Frontier Imaginaries: Trade Markings,” 2018, Van Abbemuseum, Nederland. Courtesy of Van Abbe Museum

DENG Liwen (Zoénie) is an art writer, researcher, and translator. She is currently pursuing her PhD in the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ACSA), University of Amsterdam. Being part of the project ChinaCreative funded by a consolidator grant of the European Research Council (ERC), her PhD project focuses on criticality in socially engaged art in contemporary China. Her research and artistic interests cover social practices, feminism, the postcolonial, art and activism, and critical ways of living together. See also http://chinacreative.humanities.uva.nl.

1. Walter Benjamin. The Arcades Project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002: 462.

2. Vivian Ziherl. Introduction Frontier Formalism. http://frontierimaginaries.org/organisation/essays/introduction-frontier-formalism. 2016. Last access 28th April 2018.

3. From the author’s interview with Vivian Ziherl on 23rd April 2018, in Amsterdam.

4. The University of Newcastle, Australia, A map of more than 150 massacre sites of Indigenous people, https://www.newcastle.edu.au/newsroom/featured-news/mapping-the-massacres-of-australias-colonial-frontier. 5th July 2017. Last access 29th April 2018.

5.Ibid.

6. Calla Wahlquist, “Map of massacres of Indigenous people reveals untold history of Australia, painted in blood”, the Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/jul/05/map-of-massacres-of-indigenous-people-reveal-untold-history-of-australia-painted-in-blood. 5th July 2017. Last access 29th April 2018.

7. Merrillees, Scott. Jakarta: Portraits of a Capital 1950-1980. Jakarta: Equinox Publishing. 2015: 60.

8. From the author’s interview with Vivian Ziherl on 23rd April 2018, in Amsterdam.

9. From the wall text of this artwork.

10. This refugee-filmmaker is called Khadim Dai, and he has written an article on his experiences and works: http://frontierimaginaries.org/organisation/essays/frontiers.

11. Brian Massumi. Politics of Affect. Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA: Polity, 2015.