The Pillow Book: A list of things it is not

| September 3, 2018

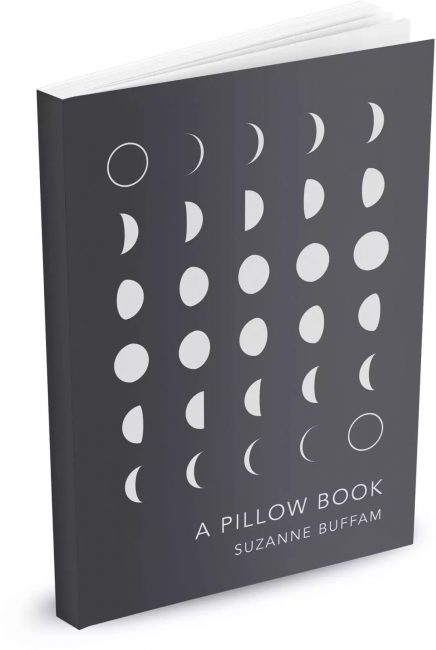

Inside a moon-like circle on the back cover of The Pillow Book is a list of things it is not: “Not a memoir. Not an epic. Not an essay. Not a spell. Not a shopping list. Not a nocturne. Not a dream book. Not a prayer. Not a novel. Not an apology. Not a dossier. Not a complaint. Not a manifest. Not a manifesto. Not a field report. Not a promissory note. Note a recipe. Not a résumé. Not a confession. Not a lullaby. Not a secret letter sent through the silent palace hallways before dawn”. Slightly above and to the left is a much shorter list, of the categories under which it should be shelved: “Poetry/Non-fiction”. But it is also not poetry, and not non-fiction.

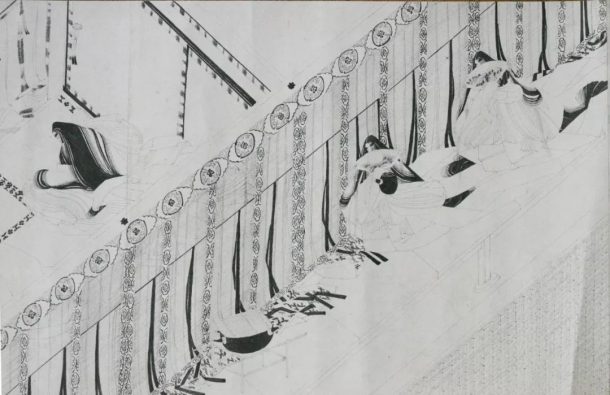

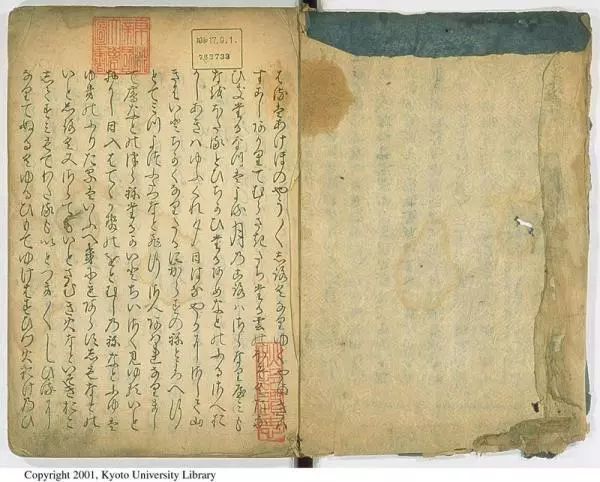

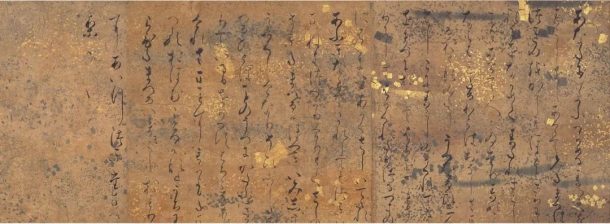

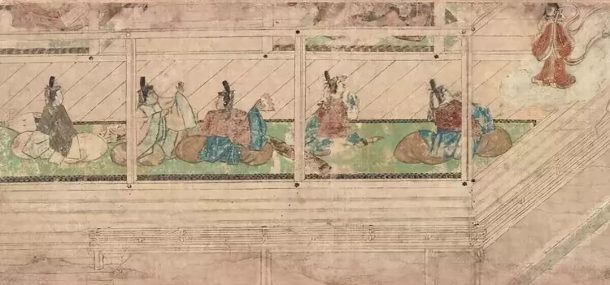

There are many things The Pillow Book is not, but also many things it is. A reflection on marital life. A book about insomnia. Or as the narrator herself considers at one point, a book about someone with insomnia writing a book about pillows. Considers, and rejects. Most obviously, it is a homage to Sei Shōnagon, the Japanese courtier whose collected writings have traditionally been published under the same title, though it is unknown whether she herself referred to them that way. In fact, part of the list of things it is not appears in The Pillow Book itself, applied instead to Shōnagon’s text to evoke the elusive form in which it has been transmitted to us by history.

There are indeed many similarities between Buffam’s Pillow Book and Shōnagon’s Pillow Book. Both address a variety of apparently unrelated topics in short pieces of prose of various forms, though Buffam’s book is significantly shorter overall and does not replicate the longer essay-like passages prominent in Shōnagon. Both feature an eclectic variety of lists. Both utilise apparently autobiographical elements with a focus on everyday life.

Of course, there are also differences. Shōnagon’s book has become one of the most important sources of information about the period in which it was written, very little is known about Shōnagon herself apart from what can be inferred from her book, and her book was not written to be read by others (or so she claimed, though this was famously disputed by her great contemporary Murasaki Shikubu). Each marks an obvious contrast with Buffam’s book.

More significant differences concern form and content. The original order of Shōnagon’s book is unknown. Indeed, it is unknown whether it even had an original order. Buffam’s book on the other hand has clearly been arranged to produce a particular emotional, if not narrative, arc. Moreover, as the list of things it is not makes clear, Buffam’s book is pre- occupied with its own status with respect to traditional forms in a way that Shōnagon’s book is not. In this respect, The Pillow Book resembles the quasi-novels of David Markson. In fact, in hindsight it is remarkable that Shōnagon, so attuned to nuance in everyday speech, and so concerned to uphold the norms of poetry and letter writing, gives so little attention to the cumulative form of her own writing.

These differences give The Pillow Book a subtle power. It is at once a meditation on sleep and writing that reaches back to the elusive Shōnagon, and a meditation on the nature of poetry, memory and dreams that implicitly addresses the question of what writing attuned to our contemporary situation can be.

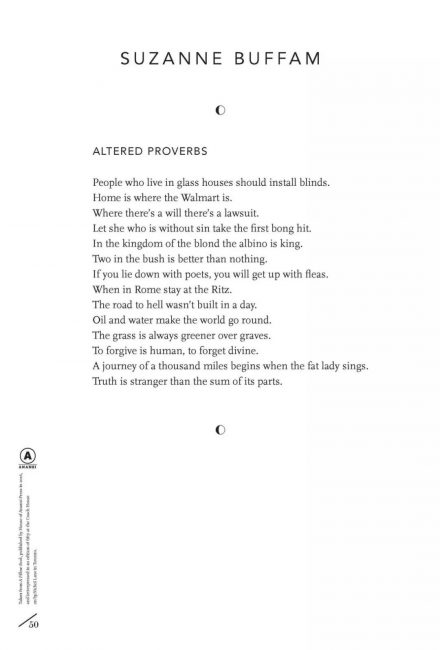

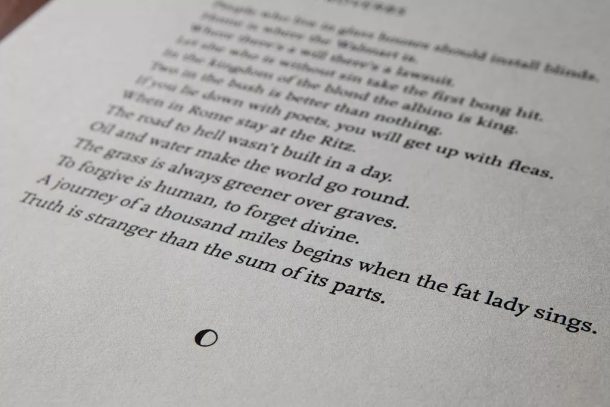

There are places it falters: the lists aim at humour with variable success, and one passage about the narrator’s Puerto Rican nanny is difficult to read with charity, given that class is mostly buried rather than explicitly addressed.

Ultimately, it seems to me that the book is not in fact fundamentally about sleep, dreams, memory, poetry, or writing, but about the invevitability of death and the uselessness of our efforts in response to that fact. We can recite our proverbs, interpret our dreams, make our jokes—but these are laughably arbitrary practices, and in the end we will be lucky if our bedside notes survive to be read a thousand years hence. Either way, the ultimate cure for insomnia waits for us all. These sentiments pervade the book, at first submerged, before rising to the surface in the final pages: “We are dead, I repeat the next day in my head, as we hurtle downhill on a blue plastic sled”.