On Diaspora and Dialect in The Wild Goose Lake

| June 19, 2020

The film The Wild Goose Lake (2019) is set in a nondescript space that contrasts starkly with its explicitly stated timeframe, namely the year 2009, when China had not yet been overrun by highspeed railway and WeChat—the geographic and digital infrastructure networks that assure at once mobilized individuality and surveillance. In the original Chinese title of the film (Nánfāng chēzhàn de jùhuì)—“Meeting at the Southern Train Station”—the word nánfāng, or “southern,” points to an absence of the north. This marks a departure for the film’s director, Diao Yinan, from trusted locales of North China and Northeast China, not to say an act of internal diaspora for Chinese art cinema.

Said diaspora is different from that of emerging younger-generation filmmakers focused on autobiographical and local stories. Following the rapid tightening of politics and the marketplace, young filmmakers are no longer offered a subject-position in the national narrative of “Chinese Cinema,” this is even the case for iconic young directors with resources at their disposal such as Bi Gan. The 1980s-born director Qiu Sheng, hailed as a representative of the “Hangzhou New Wave” of younger, locally focused filmmakers, has asserted that “no legendary success story like Jia Zhangke can arise in China ever again.” That being said, the younger generation’s narratives show a greater richness and openness than those by Sixth-Generation filmmakers. Worth considering is the possibility that the subject-position of “Chinese Cinema” has resulted from collusion between established, increasingly ossified European film festivals and Sixth-Generation filmmakers, entailing an ad nauseam reproduction of stale national narratives. Those narratives are oftentimes tongue-in-cheek, as is illustrated by the whispered plaint of a laid-off worker whose only child has passed away, in Wang Xiaoshuai’s So Long, My Son (2019): “Beijing really has changed a lot.”

It is worth thinking of The Wild Goose Lake as a diasporic Chinese film not only because Diao Yinan has already achieved a national narrative in his 2014 film Black Coal, Thin Ice, but more so because The Wild Goose Lake has abandoned the logic of cartographic design typical of Sixth-Generation national narratives. Black Coal, Thin Ice successfully laid out a subtle cartographic design: a serial killer takes advantage of his job as a weighman in a transport hub to drop dismembered bodies into freight trains departing for various destinations, thus scattering human remains across the country in the span of a day. This imagery utilizes the national economic development campaign “coal transportation from north to south,” visualizing individual violence as geopolitically structured violence. However, cartographic design can only respond to existing geopolitics, rather than altering them. When cartographic design is the only unbreakable frame of reference in global and national orders of art cinema, what remains is the endless multiplication of “Chinese imagery” such as that of the urban village, the boss’s mistress, the disco ballroom, the bullet train, and the foot-massage parlor. The reality of China is no longer palpable.

The leads in The Wild Goose Lake, Hu Ge and Gwei Lun-mei, have adopted the Wuhan dialect for the film, yet neither try to pass themselves off as Wuhanese, nor attempt to perform any “Wuhan-ness.” The film is not presented to the viewer as a local story. Conversely, some films that deliberately externalize Wuhan’s regional characteristics use Mandarin instead of the Wuhan dialect. For example, seen through the lens of filmmaker Lou Ye, Wuhan is defined by its equal distance from the northern political center of historical trauma and the southern ahistorical land of new economic order: in Summer Palace (2006), having fled Beijing, protagonist Yu Hong is unable to adapt to Shenzhen, prompting her to turn back and settle down in Wuhan; the Wuhan depicted in Mystery (2012) becomes a visual toolbox used to represent acute class stratification; in that vein, Wang Xiaoshuai’s So Close to Paradise (1998) and Wang Jing’s film Feng Shui (2012) both found inspiration in Wuhan’s historical Hanzheng Street and its characteristic porters with carrying poles (biǎn dan). This sort of localness is generally intrinsic to the system of cartographic design.

Why is dialect used in The Wild Goose Lake? Perhaps films that make use of dialect stand in opposition to the notion of “accented cinema” coined by scholar Hamid Naficy. If Naficy’s “accented cinema” refers to the bilingual practices of exiles and migrants under economic neocolonialism, then here “dialect cinema” can be seen as the transcendence of Chinese language orthodoxy that epitomizes the internal order of “Greater China.” The film’s unambiguous English title—the eponymous fictional lake—evokes a profane world far removed from any center, a veritable no-man’s-land made up of demolished areas, full of vacant buildings where loiterers gather and people are about to be “combed out street by street, building by building, person by person,” to quote a policeman from the film.

In the same way that not all films featuring accents constitute “accented cinema,” not all films using dialects are “dialect cinema”: Kaili Blues (2016) is one, while Chongqing Hot Pot (2016) isn’t. In fact, the dialect worlds of The Wild Goose Lake and Kaili Blues have a mutual affinity: the protagonists lose all personal connection with the world as they frequent the underground spaces of organized crime, while the worlds themselves—respectively Wild Goose Lake and Dangmai—manage to retain their potential for redemption against all odds.

Many categorize The Wild Goose Lake as film noir, with which I disagree, nor do I agree with claims that the film “doesn’t measure up to the standards of film noir,” or that it is “merely a male-centered film noir.” Film noir is part of a deep, expressive tradition of modernity. Any attempt to under- or overestimate film noir would be ahistorical. Even though scholars have never achieved an agreement on the definition of film noir, and it is still difficult to clearly distinguish film noir from crime films and gangster films, I subscribe to the views of film scholar Dan Flory, who sees film noir as an epistemological model: in the process of getting to the bottom of a case, the investigator-protagonist discovers an overwhelming, oppressive social structure. Film noir originates in the rise of U.S. hegemonic power after the First World War. Its symbolical, boldly contrasting tones are there to complement a moral and ideological grey zone, that critical state where the descent commences from an orthodox world into a profane one, and the American dream devolves into an American nightmare. However, from the get-go, The Wild Goose Lake is a profane world made up of outcasts, existing in a time prior to a state of total surveillance (2009), where pilfering gangs and the police use the same methods to divvy up their urban turf. Our protagonist, Zhou Zenong, is focused on his own imminent death, and has no intention to provide new insight into the social world.

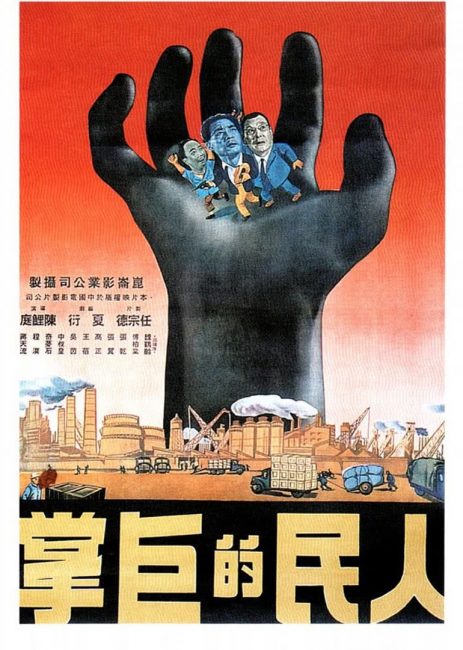

The Wild Goose Lake is a diasporic film not only because it departs from the cartographic system that is at the center of current Chinese art-cinema, but also because it departs from the “counter-espionage” genre emblematic of official crime-drama traditions. Scholar Lu Xiaoning defines the Chinese “counter-espionage” narrative that arose during the 1950s as “participatory surveillance”: the pursuit and capture of antirevolutionary spies contingent on the vigilance of ordinary folk providing clues and showing the way for the sake of upholding public security. The mobilized masses become agents of surveillance rather than its targets, comprising the inescapable “Long Arm of the People” (1950). In contrast to counter-espionage films, the groups of lakeside tourists, residents of tongzilou (collective apartment buildings from socialist times), and factory workers waiting to be dismissed in The Wild Goose Lake provide some final refuge for wanted criminals. These complex, deterritorialized groups that are excluded from the normal social contract have the power to counterbalance technological surveillance. The film’s whopping 3,000 extras are not portrayed as “people” as such. Following Zhou Zenong’s escape, the film shifts from the otherwise single-willed “people” of counterespionage films to a disgruntled, muttering “multitude.”

Diaspora is never an easy way out. There is no assurance of success for such act of internal departure. Nevertheless, it is equally impossible to find liberation in an irrational Hobbesian world of crimes as in a totalized rational world of surveillance. Thus, Zhou Zenong’s rational death plan has played out as one of the most utopian and romantic pursuits in recent cinema.

Zoe Meng Jiang is a critic and teacher based in New York, currently a PhD candidate in Cinema Studies at New York University.