AUTOGRAPHICAL AFFAIRS

| November 9, 2015 | Post In LEAP 35

Traditional Chinese painting, known colloquially as a “tasteful debt,” has become an increasingly important part of the economy of gifting. Its role as an unspoken tender allows ink to become a mirror that reflects the true complexities of the interpersonal relationships arising from man’s unquenchable thirst for power and ability or willingness to navigate this space. In the study of both art history and political history, Chinese painting is a highly fertile medium.

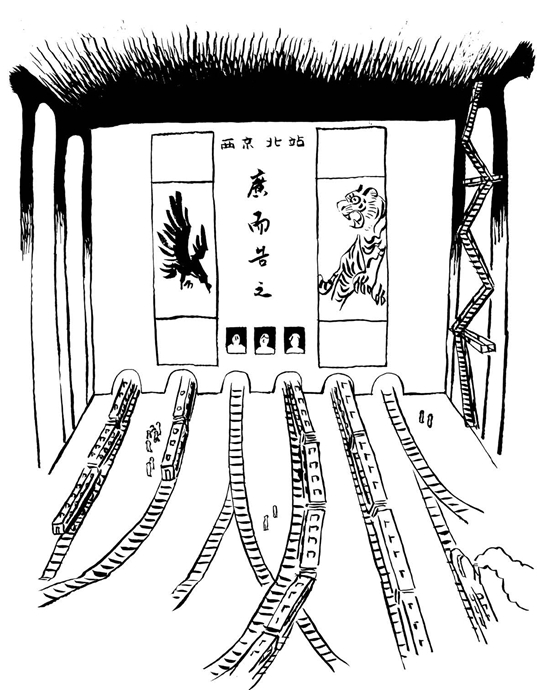

Following the founding of modern China in 1949, the country soon abolished the previous market economy model and implemented socialist reforms. Artists were organized into associations and placed in calligraphy and painting academies, academies of fine arts, and art and craft factories. Many artists drew salaries from their places of employment and occasionally temporarily transferred to government auditoriums or hotels to create large-scale decorative paintings. The government provided room and board but offered no other additional compensation.

Chinese traditional painting, as an accessory to the ideologies of the time, could not yet serve the function of the tasteful bribe, but the practice of gifting artworks between artists and people in power was still commonplace. The bribing function of the practice was rather modest, compared to the purpose of displaying both the artist’s popularity and the good taste of the recipient.

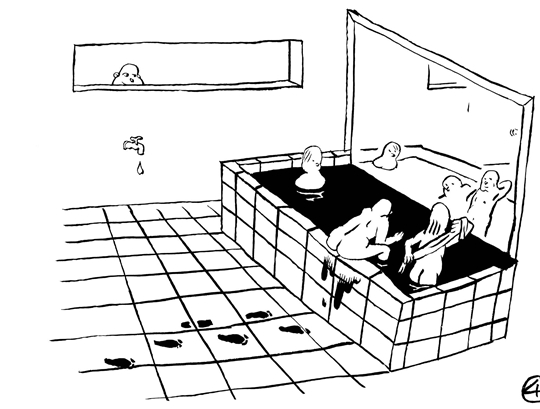

much to the imagination, as he reportedly drew Jiang Qing in the nude in his early years.

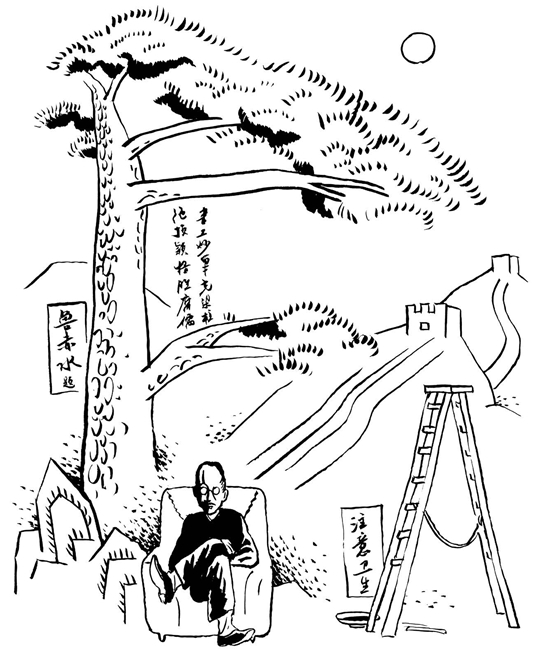

In modern times, to become a master of traditional painting one must carry on the essence of traditional culture, shoulder the heavy ideological responsibilities of the time, and engage the sincere and earnest trust of the top leadership. In practice, this means that painters must play the administrative game of actively partaking in large-scale exhibitions and themed collective projects organized by the government, joining artist associations, achieving professorships, and occupying administrative positions at art institutions or art associations. They must also manage themselves like celebrities by organizing solo exhibitions, publishing personal catalogues, and facilitating one-on-one interviews by the art sections of popular mass media—the longer the story and the bigger the photographs the better—before one could possibly enter the scope of considerations for tasteful bribing to begin.

Around 2009, several hundred clustered art galleries appeared in Qingzhou, Weifang, and Jinan, all in Shandong province. The vast majority of the proprietors had scant knowledge of art and lacked the ability to evaluate the works that come across their desks. To them, value lay only in the title and perceived fame of the creator of the piece. These galleries secured funding through local bank loans and, when faced with insolvency, would assess the works they held and submit them to the banks for collateral. This practice helped promote the rapid expansion of the calligraphy and painting economy, but, due to its crudeness and clear market motivations, the ensuing prosperity did not last. Most of these galleries have either shut down permanently or been sold to those able to adapt to the evolving market environment.

Text by Wu Jianru

Translated by Frank Qian