LIU YIN: DISSOLVE

| December 23, 2015 | Post In LEAP 34

Woman Jumping off Building, 2015, acrylic and pencil on paper, 109.2 x 157.4 cm

Liu Yin has realized, like most of us, that she spends far too much time browsing news and advertising images. This tremendous swatch of visual information has long been part of our lives, but its intrusiveness has risen to historic heights thanks to the pervasiveness of the smartphone. News images, an important means to visually record and disseminate what is happening around us, constitute a raw database that makes visual critique and research possible. Almost out of instinct, Liu began to use and modify found images in her drawings in 2012.

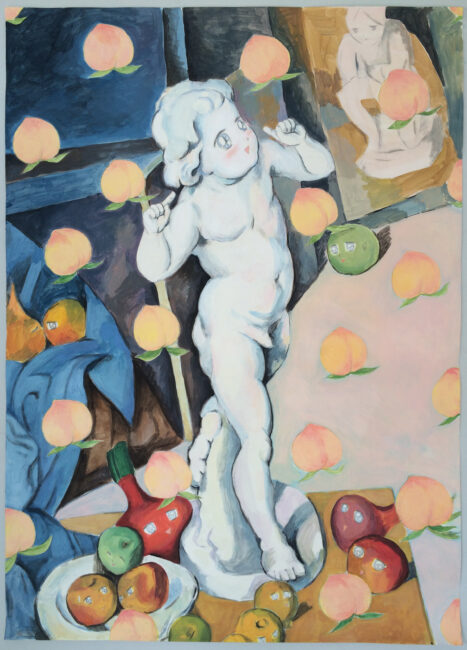

Cupid, 2015, Pencil, watercolor, acrylic on paper, 78.7 x 109.2cm

The image used for the 2013 piece You’re Worth It comes from a L’Oréal ad that was commonly found in fashion magazines. Liu layers propylene pigments in the tones of foundation makeup on the faces of heavily digitally modified models. The resulting cartoonish effect, particularly applied to the eyes, apropos the modern aesthetic preference to focus on specific aspects of the female body, highlights the emptiness beneath the shiny exterior. Overly emphasized eyes embody the very concept of the gaze. As part of her bid to question this caricaturization of the female image, Liu exhibits a milder feminist stance that swims between the extremist academic perspective and the subconscious, commoditized treatment of the fairer sex. More importantly, as she brings the three-dimensional photograph into a two-dimensional cartoonish representation, the hypocrisy hidden behind the veil of the public image is revealed; the concept of manufactured beauty thus takes on a more direct and literal significance.

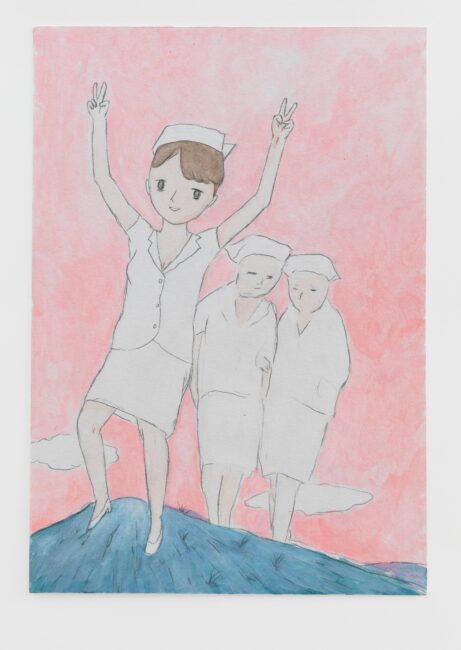

Mountaintop, 2009, Pencil, watercolor, acrylic on paper, 14.7cm x 21.2cm

Liu discovered the power of this tactic as applied to news images, and began to use it in a series of paintings. Woman Jumping off Building (2015) is a perfect example. In this diptych on paper dominated by the season’s most popular maroon color tones, Liu continues to apply her signature manga-style sparkly eyes, and further enhances this dreamy effect with exaggerated colorful halos and floating lemons. Details at the bottom right corner of the painting—a cat and a large strawberry in a window—speak to the cartoon nature of the piece. Liu uses aesthetics typical of Japanese manga to arouse a sense of the halo of love. The violence and pain that make up the subject matter of the image dissociated on the surface; only with further examination does the viewer realize its inner cruelty. To some extent, Japanese manga and western romance novels serve the same social function, creating an idealized fantasy founded on pure love that, regardless of plot or narrative, always ends in the happily ever after. The scene described by the painting is, in a way, the cruelest of reminders of this man ufactured perfection. A seemingly sweet layering of colors is a sharp sword wielded against both the manga format and the fantasies created through it.

Stephen’s fantasy, 2015, pencil, watercolor, acrylic on paper, 78 x 79.5cm

In her subsequent piece Handshake (2015), we witness one of the most important moments in the history of Sino-Japanese diplomacy: a handshake between two heads of state, each sporting the hairstyle unique to successful politicians—but the scene is set in front of a powder blue background, and both heads of state sport an unnatural reddish hue to their faces reserved for cartoonish treatments. When photos of this painting circulated on social media, one person living and working in Japan asked with concern if work like this could be exhibited in public at all. The sensitive nature of the painting is readily apparent, but it’s simply too delicate to point out the political incorrectness directly. There is an entire group of Liu’s works that falls into a similar category. Their existence stabs dangerously at certain taboos as much as they slide the viewer into an alternative visual interpretation with perfect ease. Liu finds a crack through which she can maneuver both the real-world event depicted in the image she processes as well as the visual language she employs such that both are rendered distorted and ineffective; this juxtaposition draws viewers to the finished pieces. As early as 2007-2010, Liu painted a large number of smaller individual pieces marinated in bad taste, such as A Lady with Moustache (2009), Ballerina (2010), Live Broadcast (2009), Let It Breathe (2009), and Mountaintop (2009). On the surface, she was examining young women’s adolescent anxieties, but, in fact, she was experimenting with the power of the cartoon drawing to circumvent traditional realist art education and present social commentary.

Ballerina, 2010, folding table, egg, 74cm x 50cm x74cm

As she perfected her narrative strategy, Liu took her experiments one step further, realizing that she had formed a grammatical strategy shaped by the language of her brush. Liu is well aware that she’s not actually drawing cartoons, just as she is aware that her work is different from the pure painting accepted in the institutional context of art. She is perfectly happy with this no man’s land, not bothering to hide her cynicism and resistance to realism. When she affixes a flat cartoon face to a classical bust (Gaze, 2010), Maurizio Cattelan himself couldn’t help but chuckle at the outcome.

Liu’s fascination with this state of in-betweenness, which radiates and expands from her artistic treatment of found images, is further reflected in a neon installation made from the artist’s childhood sketches (Rabbits, 2014), a blue pail filled with water (Doraemon, 2011), and an egg precariously placed at the corner of a table until it is knocked over by an unwitting viewer (Ballerina, 2010). Through her visual language, Liu challenges both the serious art ecosystem, whose rules govern her despite her rebellious nature, and the predilections of the dominant youth culture. Meanwhile, her deft touch creates a playful, childlike experience, dissolving any tension that may have arisen due to the sharpness of her criticism. (Translated by Frank Qian)