ON WANG YIN: TOWARDS A POOR PAINTING

| July 28, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

When you turn on the television in China and flick through some channels, chances are you’ll happen upon several TV series set in Republican-era China. This is nothing new; Republican Fever, as it is known in the media, has been part of the Chinese contemporary reality for many years now. It started at the turn of the 21st century when many important books from the Republican era became available for the first time, prompting heated intellectual interest and many new books on the subject. Culture of that era initially represented an alternative to the perceived cultural indifference and materialism of today, and allowed intellectuals to reimagine their own identities—where they came from. This spilled into TV with the advent of Republican-era spy dramas, pitting the Communists against the Kuomintang in the beautifully nostalgic settings of Art Deco Shanghai. The unexpected popularity of these programs allowed the Communist Party to reiterate its roots as an underground revolutionary movement, resulting in the ongoing interminable run of such period dramas.

On the surface, Wang Yin’s work seems to be part of this new intellectual and political trend of looking back at China’s modernist roots. But, with him, it started in a different way, and far earlier. As both his parents were artists, Wang grew up in an environment where socialist realist painting was part of the everyday fabric of existence. He grew up painting in the formal and theoretical certainty of the style until that simplistic perspective was shattered by the mid-1980s, with the eruption of the 85 New Wave movement. Almost overnight, the previous “truth” of socialist realism was written off as reactionary dogma. Artists abandoned the old order in the excitement of discovering new worlds. During this time Wang embarked on a similar journey of exploration, but with one important addition: he also discovered the world of avant-garde theater when he entered the Central Academy of Drama in 1984. During the excitement of the 1980s, when the fruits of 20thcentury western modernism flooded all at once into consciousness, the written word was king. Poetry, literature, and philosophy were the currency of students and intellectuals. Art, film, music, and theater relied on resources not yet available at that time. Art catalogues were poorly printed, and before the advent of cheaply reproducible CDs and DVDs music and film were restricted to small, inner circles. Experimental theater that relied on live performance was possibly the least accessible of all art forms. Yet, in the thick of the most potent period of Chinese artistic experimentation, Wang studied theater. What he discovered during that time was the work of Jerzy Grotowski, a Polish theater director whose approach is highly theoretical and process-based, with a rigorous doubt of novelty and spectacle. In his book, Towards a Poor Theatre, Grotowski writes,

The Rich Theatre depends on artistic kleptomania, drawing from other disciplines, constructing hybrid-spectacles, conglomerates without backbone or integrity. […] No matter how much theatre expands and exploits its mechanical resources, it will remain technically inferior to film and television. Consequently, I propose a poverty in theatre.”

What Grotowski proposes is a return to the roots of theater in order to formulate a pure engagement between actor and audience. This is not a reactionary return to traditional form, but rather a filtering out of contemporary (and temporary) fanciful distractions in order to hone in on what is most essential to theater. Only by consciously breaking from old conventions and steering clear of contemporary trends can he arrive at a radical new form. Upon graduating from the Academy, Wang Yin embarked on the vocation of being an artist armed with Grotowski’s rigorous criticality, which contrasted strongly with artists of that time. Being “experimental” generally meant working in an artistic style found in recent western art history, be it neo-expressionism, pop art, installation, or performance. These were exciting new pastures for a generation of artists who redirected the course of Chinese contemporary art, arguably making it what it is today. However, in a brief story Wang wrote in 1992 titled “Excerpt One,” he has already decided to work in a totally different direction:

Several years ago, and at my own request, I was permitted to leave everyone, leave my own tribe to guard a shabby frontier far away from here. For my tribe this is an insignificant place; a wasteland the size of a postage stamp that only exists inside people’s consciousness. Nobody talks about it, takes it seriously, or even remembers it.

This pitiful and neglected wasteland that Wang Yin decides to make his home can be interpreted as our Chinese modernist past—something shared by almost all artists of that time, willfully suppressed like a psychological wound. If Grotowski’s work taught Wang anything, it was not to avoid novelty for its own sake, but to search for true radicality in the roots of an art form. The fact that his peers regarded their modernist heritage with such disdain may have been an indication for Wang that something was hidden there, something worth looking for.

Modernism is a cultural movement that ostensibly looks forward, discarding a dark and oppressive past in order to unlock the door into a bright new future. Chinese modernism took this to an extreme, attempting to deny or even eradicate the past as part of its process, ultimately resulting in the “Destroy the Four Olds” campaign of the Cultural Revolution. So, during the 1980s, when Chinese artists were liberated from this extreme political predicament, the sudden freedom they enjoyed allowed them, yet again, to discard a dark past in order to unlock a door into a new future. It cannot have been an exaggeration for Wang Yin to describe his field of attention as a forgotten wasteland. But, more importantly, his decision to look back at recent history strikes at the very heart of the modernist project. This is the radicality of his work: not just exploring a certain style or media, but taking on cultural ideology itself. Intentionally or not, this attitude towards the past made Wang Yin one of the first truly contemporary Chinese artists, recognizing and moving on from the kind of traditional modernism that was still holding most artists back. Of course, this does not guarantee good work; it only forms a basis from which a body of important work can emerge. But the thinking behind his decision allows us to better analyze the content of his paintings. In order to do this, it’s important to acknowledge that, although Wang’s work refers to the past in various ways, it is firmly about the present. His painting takes us on a particular journey through time, but we always arrive back in the present. This is what sets it apart from nostalgia. Nostalgia also takes the viewer back in time, albeit in order to artificially keep the viewer in the past—a past distorted by romanticism.

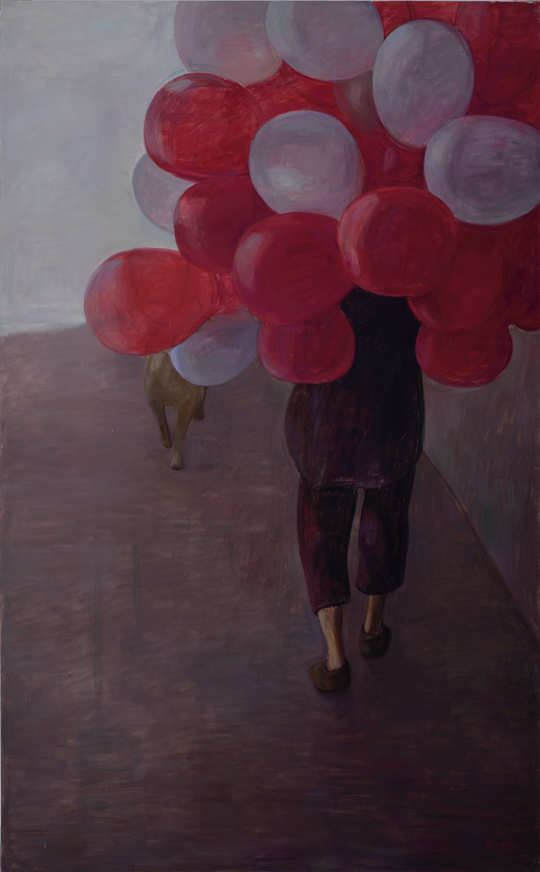

In Wang Yin’s work, the past serves as a kind of filter to better understand the present. While his early work of the 1990s takes on the past directly, only leaving clues as to its true contemporary nature, his recent work uses the past to reformulate meaning for the present. One example is the lack of detail in his paintings, almost like he is painting from an incomplete memory. It is often the most important details that are lacking, such as faces. Most people have had the experience of trying to remember someone’s face, the constant failure to remember specific details, rendering the memory impotent and resulting in frustration. But the scenes in Wang’s works are not his memories; they are often painted from reference media images or photographs he took. The paintings seem to approximate the state of remembering itself. Rather than personal memories, his works are closer to a common state of remembering for Chinese people in the here and now. That is why many scenes feel familiar to Chinese viewers, but not to others. The act of remembering, however, is something one can only do from the present in relation to the past—a twentieth-century past in which the act of remembering was discouraged or even forbidden. Its memories are incomplete, as if we’ve forgotten how to remember properly. This is made more apparent when Wang repeats compositions, introducing changes and even incongruous content over time. These out-of-place elements often include people in ceremonial minority dress: images taken from tourist brochures or coffee table books on Chinese minority cultures. The standard imagery is of beautiful girls, carefree and smiling, in national costume.

Although very few Chinese people have met such exotic creatures, they form part of the national consciousness, and can be considered “memories.” Yet, these memories are not personal—fabricated by state ideology and mass media—so Wang Yin’s compositions impersonate this mnemonic process, planting impersonal memories into familiar scenarios. This is one of the ways in which ideology works: when personal experience is replaced by external ideas, the subject becomes part of a larger constructed consciousness. See Birthday (2008) and Birthday No.2 (2010), two paintings both featuring a candle-lit western-style dining room in which two minority girls pose for a camera to the viewer’s left. The scene of the earlier work has many more details than the later one, such as food on the table and a back wall packed with early Chinese oil paintings. The later work empties the composition to focus on the two girls, allowing their artifice to become more apparent. Their pose and gaze suggest the presence of someone outside the picture, and they are lit from a light source separate from the candle directly in front of them. Here, Wang uses the tools of painting to cut and paste the girls into the picture as if they were collaged from a magazine, just as the ideology behind such magazines is inserted into our consciousness. As ideology needs only archetypes in order to function effectively, Wang Yin needs only to paint archetypes to conjure up their rhetorical potential. But, in the process of playing with time and ideology, he forces the viewer to slow down to meet his sense of time. Time spills out of the canvas into the exhibition space, into the relationship between viewer and work. This is perhaps where we are at our closest to Wang, in conversation with him, trying to understand him. Sometimes this is hard work, but the reason why we try is because, in the back of our minds, we suspect that, through this process, we may learn something about ourselves. Wang pares things down in order to develop a particular relationship between work and viewer. It is no coincidence that Wang Yin’s painting lacks a richness of color, texture, or style—it’s because, like Grotowski, he aims for quite the opposite.