PERFORMANCES I HAVE (NOT) SEEN

| December 22, 2015 | Post In LEAP 34

What does one talk about when one talks about performance in art? Across an unmistakable recent wave of conferences, special journal issues, and survey exhibitions, performance frames a near-apocryphal field. It clusters together practices that often have more in common through what they lack than through what they share.

Perhaps it is the relative marginality of performance that has—until recently—been its mark. Difficult to collect and fraught to classify, the moniker “performance” has taken a place alongside “the global” as a meta-container for contemporary art’s great standing reserves.

The range of practices it designates is disparate, to say the least. On the one hand performance may be concerned with feminist tactical shifts away from artistic mastery and towards self-crafting. Reading towards biography and the body, American and Euro¬pean traditions of gender critique in performance might start with artists such as Claude Cahun and Valeska Gert, continuing with Carolee Schneemann, Cindy Sherman, and Valie Export as well as younger generations of queer performers, such as those emerging from the LTTR journal and collective.

Performance may also refer to histories of artist actions that arose in the former Soviet world and its peripheries. Here, the collection displays of Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana and exhibitions such as Para Site’s “The Great Crescent” point towards bodies of work that interrupt liberal feminism as the metanarrative of performance, and give rise to unconventional curatorial tactics and institutional intelligences.

Performance can also denote a conceptual approach that departs from but exceeds the live experience. For example, the 2014 exhibition “Josephine Baker and Le Corbusier in Rio: A Transatlantic Affair”—by Colombian curator Inti Guerrero and artist Carlos Maria Romero—staged both art and vernacular culture through a meeting of modern architectural functionalism with the subversive exoticism of vaudeville.

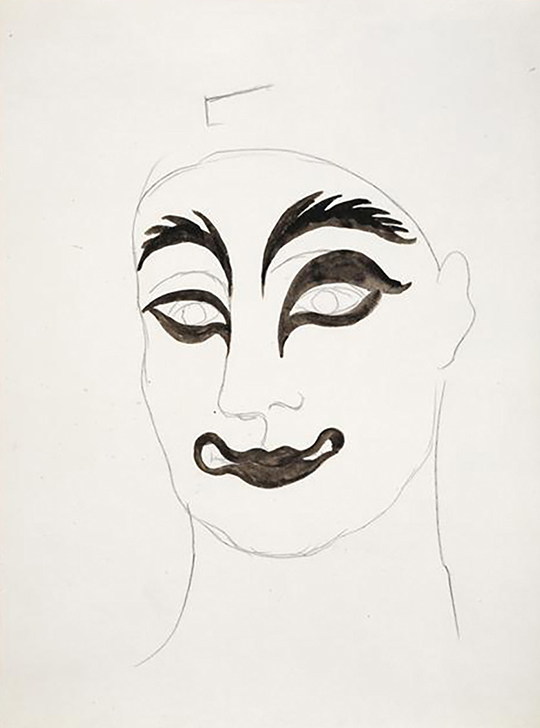

Increasingly, the practices under discussion when performance is invoked in art derive from a form of disciplinary trespass between dance and art. Here a provisional canon takes form. These often center upon the dancer-choreographers of the 1970s Jud¬son Dance Theater in New York, traced back through the studio of Merce Cunningham, and, yet earlier, George Balanchine’s founding of the School of American Ballet, with a nod to the interdisciplinary collaborations of high modernism such as the 1917 ballet Parade, which featured sets by Pablo Picasso, choreography by Léonide Massine, music by Erik Satie, and a one-act scenario by Jean Cocteau.

Many of the most recognizable performance practices in Europe and America sit within this bracket. They may include French choreographer Xavier Le Roy as well as Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, both of whom have recently exhibited in large retrospective surveys, at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies and WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, respectively.

The question returns: what is one talking about when one talks about performance in art? Or, put otherwise, what, in fact, is the object of performance amid the current conditions of contemporary art?

Arriving at this fundamental question, two practices stay suspended in mind, point¬ing to the social geometry of performance and suggesting that its true object is the polit¬ical economics of the contract form. That is to say, the ethico-juridical rearrangements of tense and obligation that have expanded the buying power of art markets beyond material artifacts and into the behavioral self-management of social contracts. The artists are Tino Sehgal and Lawrence Weiner, and it is the reading of their work as a legal poetics—rather than as bodies in space—that interests me here.

The fundamentally performative basis of classical contract theory is, according to theorist Angela Mitropoulos, “oriented to installing the future it imagines.” The contract enacts an effort to bind present to future through the outsourcing of risk and contingen¬cy. It is an effort to bring all possible material conditions into the governance of a closed social system in which the handshake binds irrevocably.

In framing a direct response to the object of performance, Sehgal, as a dancer and former student of economics, has become an almost indispensable item on museum acquisition lists. Perhaps taking a cue from Sol LeWitt’s “Wall Drawings” (1968-2007), Sehgal continues the reduction of art to its most basic principles—moving beyond the detourned commodity of the readymade and towards a human medium of what Sehgal calls the “situation.”

In securing a place for his live art in the museum, however, Sehgal’s chief achievement is as much the production of a new form of contractual art as the opening of art institutions to a new wave of performance. Through keenly engineered oral agreements that are signed in a handshake, Sehgal uses the performative register of language and gesture to produce a performance commodity of time and self-management. In short, the audience and its social experience become the object of art to be traded between artist and collector, buyer and seller, in advance of its happening.

Perhaps, in this sense, Sehgal has simply brought the art market up to speed with greater shifts in the political economy that follow from the transformation of the American dollar into a floating currency in the 1970s—the decoupling of the contract form of capital (money) from its material standard (gold). The museum is permitted to express itself, finally, as a properly algorithmic institution, in the terms of Stefano Harney: “New algorithms of management have transformed the infrastructure from one with potential for the human to emerge, to a logistical one in which the elimination of human time is the goal.”

An earlier alternative comes to mind in the 1969 “Declaration of Intent” set out by American conceptualist and typographic artist Lawrence Weiner, containing the following contractual clauses:

1. THE ARTIST MAY CONSTRUCT THE WORK

2. THE WORK MAY BE FABRICATED

3. THE WORK NEED NOT BE BUILT

[Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist, the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.]

What is rarely remarked about the canonical 1969 exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form” is its foundational place within the history of the corporate marketing of art; the project was initiated through an approach to curator Harald Szezemann from an enterprising Philip Morris marketing agent who proposed to finance a survey of the exciting new art of the time.

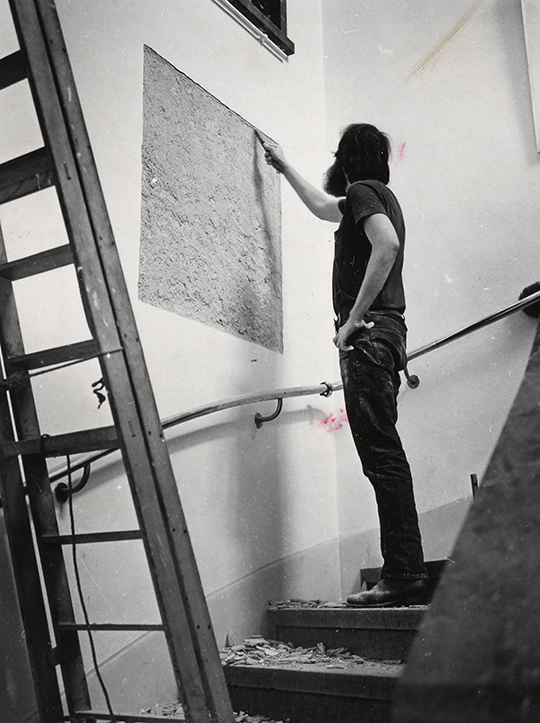

In this light, the Harry Shunk photograph of Weiner that documents his 1969 contribution to the exhibition becomes exceptionally revealing. It depicts the artist posed hard at work with chisel in hand, in front of an apparently completed work. While the artist as a performing persona may be a well-known trope, it is at this moment that the artist becomes an image valuable to corporate marketing through the intrinsic nature of self-performance to the artist’s labor.

In persona, Weiner is a confessed trickster. He cannot but play with language, placing pressure on its materialities and corrugations and tendency to catch in the mouth. In the title of his work for “When Attitudes Become Form,” Weiner all but flouts the usually rigid and functionalist language of the contract form with his A 36” x 36” Removal to the Lathing or Support Wall of Plaster or Wallboard From a Wall. In advance of the maximally capitalist realist poetics of Sehgal’s contract form, Weiner suggests infrastructures of play within the inherent loose ends of language.

Against this tangle of words, perhaps the contract form as an object of art shares the limitations of classical knot theory in geometry. Established in the 1700s, this field resolves the volume of a knot only by reimagining it as a perfectly sealed form. Knot complexity is tabulated according to the number of crossings of entangled lines that loop back together, never as an entity with loose ends. A knot with loose ends—a knot as it is encountered in the material world—cannot be calculated, just as, until recently, performance had not been subject to the value calculations of the art market.