Real Things and Actual Objects: The Survey of Capitalist Realism

| May 17, 2016 | Post In 2016年4月号

“Real things are not absolute things. Real things are the embodiments of a dictatorial system of coercion which maintains that they are real.”(1) In the paranoid milieu of the post-war order, Akasegawa Genpei’s “Thesis on Capitalist Realism” made sense: for many, discovering that the televisions, coffee tables, advertisements—the entire world—around them were a construction could seem almost a betrayal. His brand of realism is newly relevant, in advancing an art practice that models rather than represents the world.

Akasegawa, best known as a member of the Fluxus-affiliated collective Hi-Red Center, articulated the sentiments behind a global movement that would come to be known as pop art. At the time, it was called many names, including the now-forgotten moniker “Capitalist Realism.” The subject of the fall 2015 special issue of ArtMargins, a young, slim, and respected MIT Press journal that mixes articles, reviews, and primary documents, this coinage emerged simultaneously in two distant places in 1963.

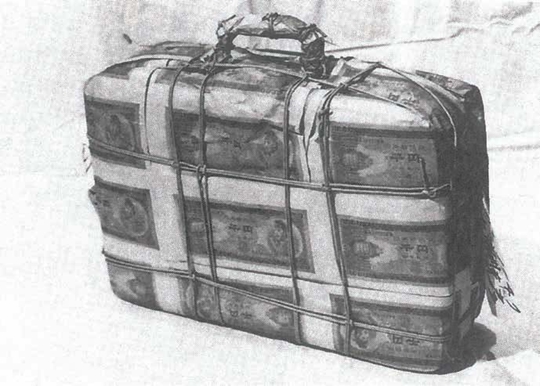

In Tokyo, Akasegawa Genpei championed the term to explain his practice. By printing money in monochrome, wrapping furniture in brown paper, or locking the doors to his exhibition, he sought to disrupt his context, normally taken for granted, and make it visible for the first time. Months earlier, in Düsseldorf, Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke, along with their lesser-known peers Konrad Lueg and Manfred Kuettner, staged an event called Living with Pop at Berges: A Demonstration of Capitalist Realism. Slightly modifying existing showrooms—for example, by spraying pine scent, hanging their paintings, and placing furniture on plinths—they turned the host department store into an expansive artwork.

By abstracting the fixtures of life in the post-war order, both projects sought to focus attention on the everyday evidence of capital. This process of abstraction differs from traditional processes of representation in which a sign is bound to an object through imitation, convention, or causality. Akasegawa studiously avoided the term “art,” opting instead to describe his objects as “models.” The process of modeling is more akin to the methods of the cognitive scientist who develops artificial intelligence to understand the brain or the urban planner who constructs a miniature city.

The Capitalist Realists took so-called “real things,” which blend into the background at the store or home, and altered them so that they popped out of their settled routines and became actual objects. This operation of abstraction drew attention to the works: when Akasegawa was dramatically summoned to court for forgery, his eloquent defense of the spirit of his work was ignored. Around the same time, the German artists used the term not only as a leftist critique or artistic tool, but also as a marketing strategy.(2) It was fitting that the member most attuned to the international art world, Konrad Lueg, later became a gallerist himself. Andrew Stefan Weiner notes the irony of the recent reproduction of the 1963 Berges show in Artists Space in downtown New York, ironically surrounded by actual luxury furniture design stores.

These models fit uncomfortably into the existing circuits of use. In Tokyo and Düsseldorf, the state and the market reclaimed the projects. A Japanese court sought to turn Akasegawa’s project into a simple forgery, forcing it into the existing taxonomy of possible acts. The post-war European art market, on the other hand, found a way to ascribe a commercial value and product pipeline to the German artists’ event.

This peculiar virtuous loop, in which an artist sells his or her criticism of capitalism on the market, makes the paradigm feel contemporary. Mark Fisher, in his recent revival of capitalist realism, applies it to the sense of inevitability of the status quo—artists involved in institutional critique and corporate aesthetics have long since mastered this sleight of hand.

Strategic ambivalence is not special to the artist, but already present in the commodity. Every product—take the ordinary chair that conceptual artists and philosophers love to bandy around—is both material and ideal. Just one in an endless series, it’s not much more than the matter that makes it up (wood, nails, and cloth). At the same time, it’s based on a standard model of a chair, a sort of ideal form.

All this leaves out the fascinating Cold War subplot. Both Japan and Germany were post-fascist countries with strong leftist movements; artists on the left were naturally familiar with socialist realism. Richter, after all, was trained as a socialist realist, and Akasegawa Genpei first exhibited in Soviet-leaning exhibitions before switching to the more modernist Yomiuri Independent exhibition series.

A word of explanation is in order about the interest of socialist realism. Because, in Marxist orthodoxy, people are shaped by social conditions, the real is obviously synthetic in socialist realism. According to Boris Groys’s Art Power, this synthetic approach explains the insistence on traditional media; if it’s all a construction, every medium and period style is as good as any other. The socialist tendency to treat the world as a matter of artifice rather than nature is crucial. Capitalism, in contrast, creates a set of artificial conditions and then proposes: “This is natural. It’s always been this way.” For a neoliberal economist, rationality is pure self-interest, while common sense indicates that many brilliant people help others at their own expense without hope of reward. (American science fiction tends to end tragically, while Soviet science fiction usually ended comically.)

This difference has ramifications for the conceptual art of the Cold War binary. While American art of the period stripped the fetish from the commodity, revealing its pure materiality, Soviet conceptualism mystified objects that had become drably standardized.(3) Whereas the former turned real things into actual objects, the latter turned actual objects into real things. Capitalist realists charted a minor tendency to create models for the commodity whose ultimate test was in capitalism itself: before the courtroom jury and the collector’s market.

For one riddle-like sculpture, Akasegawa removed the label from a can and reapplied it inside the can, reversing inside and out so that the entire world was technically “inside” the can. It turns out that there is no escape from capitalism, but at least there’s plenty of room.

———————–

(1) Jaimey Hamilton Faris, “Rooms in Alibi,” ArtMargins. Vol. 4 No. 3, Fall, 2015. p. 41.

(2) Andrew Stefan Weiner, “Stoffbilder: On Capitalist Realisms No Access,” ArtMargins. Vol. 4 No. 3, Fall, 2015. pp. 81-102.

(3) Keti Chukhrov, “Soviet Material Culture and Socialist Ethics in Moscow Conceptualism,” e-flux Journal. Vol. 29, October, 2011. Online.