THE COOL KIDS

| July 10, 2014 | Post In LEAP 27

Courtesy of Zen Foto Gallery, Tokyo

When I first mentioned the idea of making a queer cover feature to friends and colleagues, their most common reaction was “you’re going to write about that beverage?” The beverage in question is Qoo, a Coca-Cola product aimed at kids and teenagers originally from Japan and introduced to the Chinese market in the early 2000s. The company claims that the name “Qoo” came from “the exclamation of pleasure many adult Japanese utter after downing a thirst quenching beer,” and they expected the same satisfied reaction from children after drinking Qoo. They did not expect it to sound like something much more lascivious.

For the Chinese consumer market, Qoo was phonetically written as ku er, which literally translates as “cool kid.” Coincidentally, these two characters are exactly the same as the playful transliteration of the word “queer,” attributed to Taiwanese writer and scholar Chi Ta-wei in the 1994 special queer issue for Isle Margin, then the most important publication dedicated to cultural movements in Taiwan. In the late 1990s, this “cool kid” was adopted by Beijing-based sociologist, sexologist, and activist Li Yinhe, in Queer Theory: Western Sexology Thoughts in 1990s-a collection of 17 translated essays by Gayle Rubin, Steven Epstein, Steven Seidman, and Judith Butler—as well in her own collections Homosexual Subculture and Sadomasochism Subculture.

In his 1997 book Queer Revelation, Chi Ta-wei explained that the Chinese ku er is detached from both its earliest meaning in English as strange or peculiar, and from the pejorative associations of Western social discourse through the late 1980s. It is more in line with the later reappropriation of “queer” as a neutral or positive self-identifier for the LGBT community—but it blurs even this, becoming a much broader and more inclusive term. As Chi puts it, ku er queer refuses to be defined, and has no fixed identity tags. More importantly, ku er explores its own cultural perspectives, rather than aligning with other more“sensitive” social movements in Mainland China.

Li Yinhe’s books played a major role in this process, and convinced other Chinese scholars to adapt this “cool kid” to their own academic practices. Eventually, ku er managed to gain cultural status— but never outside the bubble of academia. After the failure of the social upheavals in the late 1980s and Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992, Chinese society laid any remaining radical temptations to rest, instead turning to social reformation by way of a fully free market economy. In post-1992 China—driven by the mantra “to get rich is glorious”—anything that wasn’t articulated in cold hard cash had little hope for social impact. The fall of communism had left consumerism as the best, most enabling path to an uncertain future, and generally brought a halt to the criticism, observation, and conservation of sociological subjects in China. Domestic writing aside, it was only recently, for example, that Kate Bornstein’s Gender Outlaw and William S. Burroughs’ Queer were translated and published in simplified Chinese—19 and 29 years late, respectively.

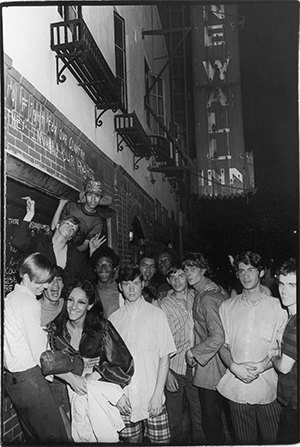

PHOTO: Fred W. McDarrah/ Getty Images

Moreover, given the centralized infrastructure and collectivist values of the Mainland, it is not hard to picture the impossibility of cultivating any subcultures which could be seen as potentially subversive. For most artists conscious and sensitive about their own homosexuality, no matter how avant-garde they may be, the safest choice is to stay in the closet. Nevertheless, their sexuality would often inevitably find its way into their work, most often subtly. Already in the mid-1980s, one would occasionally run across a canvas on which a sad young boy—as Richard Dyer put in The Culture of Queers (2001), an “image of the homosexual”— stares at you with his melancholy eyes. These boys appear in slim sweaters tucked into tight jeans, as nameless portraits of one’s life partner, or later on, with their faces covered with masks…

Hearing all this, one may ask, is it truly awful being queer in China? It is tricky. But has it ever been easy anywhere else in the world? Homosexuality was decriminalized with the 1996 amendment to the state’s Criminal Law, and removed from the third version of the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders in 2001. However, these changes brought no legal protection against discrimination or assault, leaving the LGBT community in a fragile vacuum. To put it another way, they remain invisible, enjoying freedom in a few major cities away from their small hometowns and families—until they are confronted with the pressing, stagnant, and now highly-commercialized tradition of getting married and passing on the family name. Despite this tacit nullity, the community has still generated visibility within society with recognizable living patterns and modes of dress, i.e. the sissies, the drags, and especially in recent years, the Abercrombie & Fitch clones of Gongti (an area in Beijing known for its gay scene; one may recall the Castro clones in San Francisco, late 1970s). In stark contrast to mainstream Chinese society but still not as laden with controversy as other social movements, queer character can be adapted by other social groups to serve their own purposes—even by the heterosexuals, so long as they swipe the issue of HIV/AIDS under the rug.

Thus, in this issue’s cover feature we see artists in rural Beijing in the mid-1990s employing queerness as means to further marginalize themselves, and with others in the past couple years, to stand out among their peers and predecessors. Yet given the paucity of queer art and artists here at home, we also look beyond these borders: Douglas Crimp walks us through the queer heyday of 1970s New York; Travis Jeppesen peers into the queer gaze of experimental film elsewhere in Asia; and Cosmin Costinas and Chantal Wong elucidate issues of sexuality in Hong Kong and their roots in race and urbanization. Finally, we examine queer art on the Mainland, only to discover that sometimes, appearances deceive. Bisecting these four articles are a peppering of artworks from Jaanus Samma, Wu Tsang, Wang Taocheng, and Trevor Yeung. After all, without offering the reader a glance at those sad young boys wouldn’t all this talk about queer art remain isolated within its fragile vacuum?