FANG LIJUN: THREAD OF TIME

| February 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 1

Although the word “retrospective” does not come up in Fang Lijun’s new show “Thread of Time” at the Guangdong Museum of Art (hence referred to as the “Guangzhou Show”)—the show is instead glossed over as a “case study”— looking at the vast array of biographical and historical data on display, one cannot help but wonder if Fang plans to become, at the age of forty-six, an artist significant only in memory. This is not the exhibition’s goal of course, or at least not its only goal: the show’s focus is on future “speculations.”

It must be said that this is a very well-prepared documentary exhibition, which in contrast makes the Taipei Fine Arts Museum’s show last March—“Living Like a Wild Dog: a Documentary Exhibition on Fang Lijun 1963–2008” (hereafter the “Taipei Show”) look like a dress rehearsal. The basic framing of both shows is quite similar: the curators take their cues from Fang’s biography and artistic résumé, and even many of the details on site are identical. But in comparison, the composition of the Guangzhou show is so much more thoughtfully put together that the Taipei show becomes subsumed as just another set of Fang Lijun source material.

The documentary foundation of the Taipei show is based on three previous interviews between the curator Carol Yinghua Lu and Fang Lijun, as well as a supplementary interview conducted by Kou Huaiyu. In the exhibition catalogue the dialogues cover four periods: 1963–1976, 1977–1989, 1990–1995 and 1996–2008. But in the museum the final two time periods are merged together to fit the show’s structure. In the Guangzhou show, the documentary units are readjusted to the periods 1958–1979, 1980–1993, 1994–2007 and 2008–2009; the language in the catalogue, besides a few articles in the front, is concerned with events from 1958 to today in society and politics, culture and art, and Fang’s biography. All these events are printed without omission on the walls of the exhibition hall; also the approach, coincidentally, of the Taipei show earlier this year.

The two shows are structured around key points in Fang Lijun’s biography; for example, 1977 (Taipei) was the year Fang started middle school, and 1980 (Guangzhou) the year he entered the art and ceramics department at the Hebei College of Light Industry and started to receive systematic instruction in painting. The Taipei show’s choice of structure emphasizes these biographical dates as counterpoints to dates in Chinese social history. Conversely, the Guangzhou show’s structure revolves around Fang Lijun as an individual, the most direct example of this being its tight grasp on one particular moment in time: 1993, when Fang Lijun participated in the Venice Biennale, an event whose influence on Fang and the Chinese art world has been widely acknowledged.

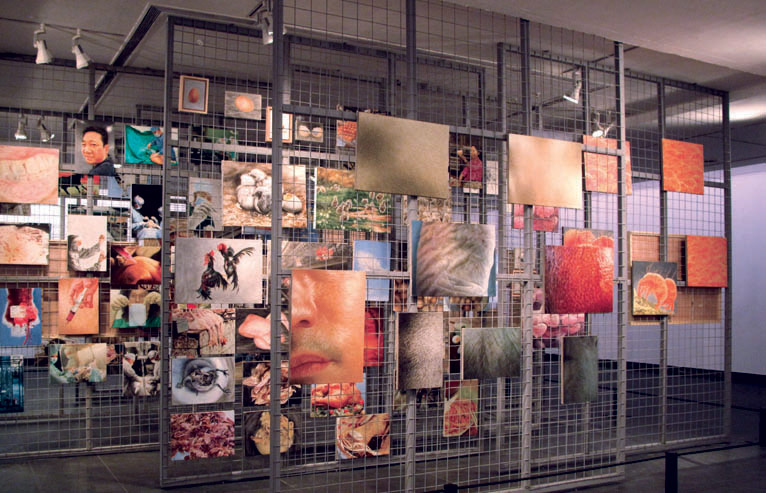

Although both show structures are inclined toward historical context, the Taipei show’s organization is much more open. We can reference the different opinions expressed in the interviews to form our own judgments and understandings of Fang Lijun’s art. Despite the materials’ subjectivity we can still experience the breadth of history as well as its coincidental nature. Yet due to the Guangzhou show’s artificially closed structure, all of Fang’s biographical details acquire heightened symbolic significance. For example, his near-death drowning experience as a child, and the many unusual deaths he witnessed before coming of age, are all tied to the topics of later works such as Swimming and Death with predetermined causality. When these personal experiences are painstakingly interspersed as concrete incidents among different moments in society, culture and art, the incidents themselves are contextualized, objectified and solidified to the point where we are left with only the mythology of Fang Lijun. Perhaps for this reason, the Guangzhou show does not record as many events in Chinese society, culture or art after 1994 as the Taipei show, instead dedicating more space to the arrangement and presentation of Fang Lijun’s biography and artistic résumé. Because these “historical materials” do not have much constructive significance in terms of reading and appraising Fang’s work (on the contrary they may have an uncontrollable negative influence on his current work), the Guangzhou show displays paintings and installations created between 2006 and 2008, as well as some of Fang’s works in progress. Finding a suitable place for these new pieces in Fang Lijun’s body of work is a problem that the Guangzhou show is most anxious to resolve, or at least clarify.

The imagery of Fang Lijun’s recent paintings is richer and livelier than his previous work, and the most notable changes are in his appropriation and piecing together of historical images, mixing these with the bird and insect images he started to produce in 2006. For example, Spring 2008, a 4 by 8.8 m black and white painting, is filled with corpses taken from real historical images: the Paris Commune, Lenin in state, Hiroshima. Meanwhile, images of flies and mosquitos hide within the frame like various colored stains. Compared to his “bald period,” the subjects discussed in the new work clearly appear much more grand and abstract, reflecting on the “big questions” such as fate, death, ideals, transmigration, history and equality of all living creatures. While this is presented as the story of Fang Lijun pushing his work out from under his bald brand, it is better viewed as the artist’s update of old symbolic imagery.

These new works, which approach psychoanalytical and ideological declarations, consciously transform the symbolism of baldness from an embodiment of the zeitgeist to a symbol of ultimate emptiness. Therefore, we have every reason to treat the new works as a blending and dilution of the old. Either way, the new pieces are bound to differ from the pre-1994 paintings because they have been intrinsically tied to the prestige of the artist from their inception—and this is the footing from which the Guangzhou show looks forward to later cashing in.

The Guangzhou show’s curator Guo Xiaoyan expresses her misgivings about its structure from an art historical angle. In an article that is not displayed but recorded in the show’s catalogue, she writes: “But in fact we notice that memory is unreliable and variable, and perhaps some of the details are not as they have appeared all along. They are not the object, and we cannot guarantee truth in the face of these moving events. But they are also not fragmentary—the practice of daily life is fully endowed with complete stories invented wholesale.” Even considering such misgivings, it still cannot be denied that this is a high-quality, once in a blue moon documentary exhibition, its controlled abundance displaying the character and maturity of both the curator and the artist. Then again, sometimes reviews are only of the exhibitions themselves and not of anything else. Sun Dongdong