AN IDEOLOGICAL REFLEX

| January 6, 2016 | Post In LEAP 36

In the mid-1990s, Zhou Tiehai and Yan Lei emerged as twin projections of a critical, and controversial, way of thinking about new art in China. “New” contra “old,” which put “new” on one side of a binary divide with “old”—read “official”—on the other. It was new as in “China’s New Art, Post-1989,” one of the early survey exhibitions, dating to 1993, which featured neither Zhou Tiehai nor Yan Lei, although it was more common to speak of “modern” or “avant-garde” art at the time. What made Zhou and Yan stand out was that neither took issue with the official opposition as such, but instead with the attitudes and practices of the home team. To the surprise of some and the dismay of many, they were self-appointed fools to the court of New Art, whose fraternities were (so it seemed to these “fools”) threatening to the natural equality of new art in China and, of greater concern, artists’ aesthetic liberty. Zhou and Yan felt impelled to highlight and satirize the hierarchical systems of influence and power that were not so much aiding the art world as controlling it.

The art world was still young in the mid-1990s, having “begun” in 1985. This may have accounted for its pervasive braggadocio, which Zhou Tiehai, in particular, found distasteful. Although Zhou and Yan were youthful elements in that art world and arguably just as full of their own bravado, their regard for truth and cynicism was beyond compare with any of their peers. In fact, the outward mien of braggadocio served to mask real concerns: as it evolved, the art world was working its way through a multitude of challenging issues, many of which had been rather unexpectedly encapsulated in the volume of singularly un-avant-garde art that was presented at the “China/Avant-Garde” exhibition in Beijing in 1989. In the late 1980s, Zhang Peili, along with a handful of others, alluded to such issues. His conceptual text works Art Project No. 2 (1987) and Brown Book No. 1 (1988), as well as the video piece 30 x 30 (1988), were conceived to test the threshold of an art world whose values Zhang had begun to doubt. Into the 1990s, Zhou Tiehai and Yan Lei raised similar issues, and were prompted to take actions that proved extraordinarily efficient means of losing friends (which, for Zhou, included artists like Zhang, whose mandate Zhou ironically upheld). At the time, they couldn’t help themselves. The need was clear, the logic absolute. “We were young and cocky. We didn’t care what anyone thought of us,” Zhou said. “We really believed we were different, that we were strong and fearless. We saw everyone around us as fake, just playing at being modern while we were the true revolutionaries.”

Here, the “we” Zhou Tiehai used does not refer to Yan Lei— Zhou and Yan were unacquainted—but to Yang Xu, with whom Zhou worked on a series of seminal works: monumental paintings on patchworks of paper as a determined form of anti-painting, which began in 1989 and which would be his first canvas for expressing his observations and concerns. Unacquainted as they were, Zhou and Yan soon came to know of each other through hearsay and comparisons drawn between the tactics they adopted. The content of their works and the titles the artists gave to them reflected their observations and criticisms.

They lived in different cities. Yan Lei was born in Langfang, Hebei, but based himself in Beijing. He was a graduate of the China Academy of Art, and his attitude followed in the vein of artists exemplified by the graduating class of 1984 and 85, who led the 85 New Wave (including Wang Guangyi, Zhang Peili, Geng Jianyi, Song Haidong), and classmates like Tang Song and Liu Anping. Zhou Tiehai was born and based in Shanghai. He graduated from the Fine Arts College of Shanghai University in 1989, describing his studies there as “smashing aside prevailing notions of what constitutes art. With Dadaism there was nothing you could not do, it ripped your mind open. One day you were listening to your teacher extol the technical merits of da Vinci, the next you could paint moustaches on the Mona Lisa.” That delicious possibility, once articulated, was like Adam in Eden presented with an apple. Unusual for the times, Zhou had also lived abroad in the doubly unusual locations of Mexico City and Kobe, and would also have a brief stay in the United States. These experiences contributed to his singular perspective.

Looking back from the international style—often surprisingly safe—of art in China today, in the 1990s artists of worth had brave new ideas and often strident attitudes. Even within this, Zhou Tiehai and Yan Lei were in a class of their own. As new and young artists, the home team’s new recruits, ostensibly they stood on the same side as the artists they challenged. In an age of black-and-white binary opposites, where new art stood outside all official culture, solidarity was deemed de rigueur. So while, in a western sense, they were doing what successive generations do—challenging the previous one in order to assert their own—Zhou and Yan were actually going up against an old guard comprised of some of China’s more remarkable artistic pioneers.

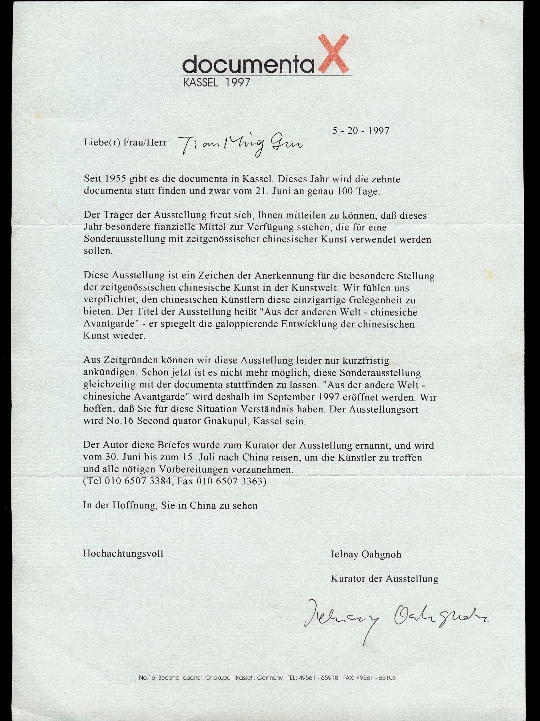

Generally speaking, Zhou Tiehai took on the art world’s relationships and Yan Lei took issue with its systems, but there was an uncanny similarity between their attitudes and the means used to convey them. While the nature of the work was not unique (Zhang Peili being the obvious precedent), they were the first of the new generation to articulate their critical ideas in so public a manner. This proved uncomfortable for artists on the receiving end, as Yan Lei (together with Hong Hao) demonstrated in 1997 with the “Documenta Scam”—a faked invitation to artists to submit materials for consideration by the curators of Documenta to which many new artists responded with hungry enthusiasm, until calls were made to the information line provided and it was discovered to be a public phone located at the Workers’ Stadium in Beijing.

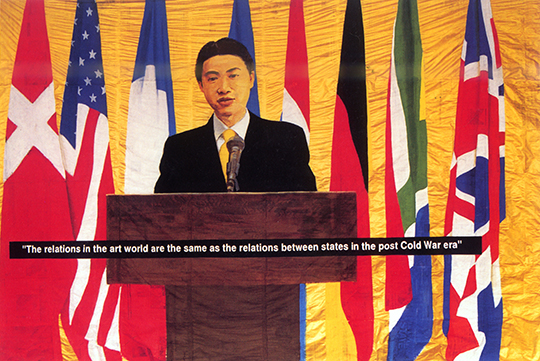

Through the mid-1990s, Zhou Tiehai summarized the urgency of “being seen by foreign curators” most succinctly in his 1996 video project Will. This showed artists presenting their portfolios to foreign curators with all the tension and anxiety of patients presenting test results a doctor. In a similar vein, in 1997, in tandem with the Documenta Scam, Yan Lei produced the collaged visual satire May I See Your Work?, an appropriation of a photo of eastern European camera engineers looking expectantly out at the viewer overwritten with the titular tag line. Continuing this aesthetic relay, the following year Zhou produced Press Conference; an image of himself as if on a podium at the United Nations with the tagline “The relations in the art world are the same as the relations between states in the post Cold War era.” Of this Yan was fully cognizant, as the fallout from the Documenta Scam soured relationships even with artists he did not know personally.

Zhou Tiehai was particularly pointed on the significance of being on a critic’s list (or not). The monumental painting Buy Happiness? You Can’t Grow up Healthy and Strong without the Protection of a Godfather (1997) captured the mood; Joe Camel peers down his nose over sunshades as if measuring our worth. The message was that “in order to grow up quickly and healthily, one needs to be protected by a godfather; if you have a godfather looking after you, your value will rise quickly.” Without one, you could kiss opportunity goodbye.

Buy Happiness is one of numerous works with self-explanatory titles produced in the 1990s including Aiming at the Museum; The Avant-Garde Doesn’t Fear a Long March (1998) and You’re Not a Hero Just Because You Showed at Venice (1999). The control of information as wielded by critics and curators was, in Zhou Tiehai’s work, extended to that of the media and its journalists. In 1993, the writer Andrew Solomon came to China to write about Chinese contemporary art for the New York Times Magazine. He acted, so Zhou Tiehai decided, “like Columbus discovering a new continent.”4 Thus, in 1996, Zhou’s first solo exhibition, organized by Hans van Dijk (as the New Amsterdam Art Consultancy) in Beijing, featured a series titled “Magazine Covers.” These pieces imitated well-known publications like Art in America, ArtNews, Frieze, Stern, and the New York Times. Zhou recreated perfectly formatted copies with headlines and images that made direct reference to the influences governing art in China at the time. The exhibition was tersely titled “Too Materialistic, Too Spiritualized,” which described the clash of emotions that underscored his generation. Today we might see that moment as a tipping point, when the balance shifted from the idealism of the older generation towards the material obsessions of the present.

The critical humor of Zhou Tiehai’s work had special appeal for foreign eyes. It was instantly accessible and unusually honest. He became close with Swiss ambassador and collector Uli Sigg, prompting a series of airbrush paintings executed in 1998 titled “Placebo Swiss,” which focused on his close relationship with Switzerland— the first of a larger series of “Placebos.” In 1998, Zhou received the inaugural Chinese Contemporary Art Award (CCAA) established by Sigg. This and other relationships opened Zhou up to accusations of hypocrisy. Following the CCAA announcement, critic Zhu Qi wrote “Recently, a Westerner […] claimed that a certain Shanghai artist was representative of China’s new, post-Cold War generation of artists. This is an utterly absurd and ridiculous statement. The artist in question is at best a second-rate artist in China. Most of his time is spent socializing with Westerners. What Westerners don’t realize is that Zhou Tiehai himself is engaged in the very activities he supposedly criticizes in his work.” Demonstrating a fine sense of humor Zhou remarked “At least I’m second rate; he might not even have ranked me at all!” The real issue was that Zhu “could say I’m not good but be unable to articulate why. ‘Socializing with foreigners’ does not stand up as a reason.”

Before the Documenta Scam made Yan Lei the subject of criticism, he came to the attention of new art circles in 1995 for a solo show in Beijing titled “Invasion,” which was curated by Leng Lin. This attention pivoted on a discussion of real and fake concerning the content of the work. “Invasion” presented videos of performance works alongside photographic representations of various acts and scenarios. The most striking visual image was a photograph of Yan’s bruised and bloodied face, supposedly following the brutal removal of a tooth. Even with the style of performance art being enacted in Beijing’s East Village at the time, “Invasion” was quite unlike anything else that had been seen, but it did not win its author instant approval. It was the first of many occasions when Yan would feel his work to be misunderstood. But if the Documenta Scam made Yan appear fearless in calling situations as he saw them, the effect touched his own nerves too, and it seemed prudent to remove himself from the mainland until emotions had cooled. In 2002, when he conceived Shanghai Welcomes Yan Lei, it was as much a riposte to the art world as a means of testing the waters.

Of course, in China change was unfolding apace, and the art world had both a short-term and rather selective memory. As the new millennium unfolded, the landscape changed dramatically. Artists were becoming far more independent and individual in practice and attitude. The sheer numbers of new artists were also changing the art world’s dynamic. As the pond expanded and divided into a multitude of small tributaries that flowed in myriad independent directions, the binary axis of the 1990s gave way to a new realm of pluralism. The critical stance that Yan and Zhou had adopted through the 1990s was, if not less urgent, at least less effective in making its point.

Zhou Tiehai followed his “Placebos” with a flood of “Tonics,” which seemed to cure him of his frustrations. In 2007, he paused his studio practice to pursue his ideals in what he deemed to be more practical ways, working to change the system from within rather than without: in 2007 he became a key advisor to SHContemporary in its first two incarnations; in 2010, founding director of Minsheng Art Museum in Shanghai; and in 2014, founding director of the West Bund Art Fair. Today, Zhou is a primary tastemaker in an art world that owes something of its equity to his presence.

In 2003, Yan Lei began the “Super Light” series of computer- generated images transferred to canvas and completed as paintings by artisans contracted for the job, brilliantly illustrating the mass consumer aura of contemporary art some way ahead of the market boom. Holding faith in his ideals and starting from the fundamental question of what art is in the post postmodern age, Yan continues to focus on the systems by which art is judged and then circulated. While he might seem to occupy less of the limelight today, he remains an anomaly vis-à-vis an art system that operates in an ever more entrenched, systemic fashion—and one day he will no doubt be recognized for this fact.