LI SHURUI: THE DIFFICULTY WITH LIGHT

| June 18, 2014 | Post In LEAP 27

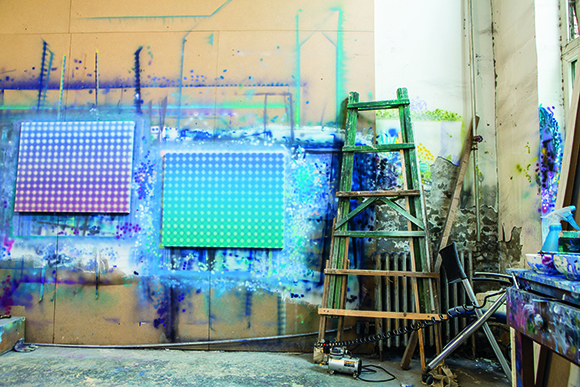

PHOTO: Li Mei

LI SHURUI’S series of paintings “Lights” has found a relatively reasoned form of visual expression, to the point where the paintings look almost too proficient. It has been nearly ten years since she began the series, with a single work called Light in 2005. T his first work was a milestone for Li. As she once explained it, when she had just graduated from the academy and came to Beijing to work as an artist assistant, she realized that it didn’t matter what she painted. In this mindset, she started to paint Light. The painting appears to depict the edge of the sun, and from the center to the edge emanate complementary colors, creating a dazzling illusion. Unlike the processes of Western Op art, which meticulously create optical illusions, Li Shurui’s initial depiction of light seems to be intuitive. Her instinct is part rebellion against the naturalistic system of art school training. More importantly, it is also derived from her experience of being an artist assistant: when what you paint is unimportant, what matters is the viewer’s physiological response. This also established the tone for Li’s later works, the majority of which explore the body’s instinctual spatial response.

Standing in front of the “Lights” series—large-scale airbrushed canvases devoid of obvious content—the viewer must overcome her visual confusion and leverage her own personal knowledge and experience to reach a more imaginative understanding of the work. Herein lies an aesthetic question—aside from immediate visual experience, what else can the viewer take away? “Lights” has in fact gone through a number of changes over the past decade. In the earliest works, the greater part of the canvas is a re-presentation of LED lights photographed by the artist, and in the picture plane the outline of a human figure can be detected. Psychedelic and flickering, these hints of narrative point have a clear meaning: the poetic expression of urban culture. Soon after, Li Shurui further reduced the realistic element to a few geometric points of light. Her paintings of this period may be closest to the Op art everyone is familiar with, yet Li’s dots of light are more emotional, transmitting the visual pulse of the city into their surroundings—not an effect that can be achieved by the deliberate precision of Op art.

Courtesy of White Space Beijing

In discussing Li Shurui in the context of the young generation of Chinese abstractionists, her work should not be positioned alongside the abstract art produced in China in the early 1980s, which was a response to the demands of formal aesthetics. Instead, it should be considered as contemporary art’s consciousness, and as a reflection on humanism and modernism. Li Shurui’s understanding of abstract art and painting is decidedly intellectual. Her light paintings are only a part of her work. In the process of figuring out how to transform two-dimensional visual experience into spatial perception, Li gradually discarded anything in her work that could be construed as a cultural signifier or as narrative. For her 2008 work A Room Called Elevator, the artist found a discarded elevator and filled it with fluorescent lights. The light leaks out through the cracks into a dark space: a scene taken directly from Li Shurui’s past experiences. Hence, although the artist considers the most important thing about the installation to be the light seeping from the elevator and arousing the viewer’s voyeuristic desire, it still draws from reality in both material and concept.

Li Shurui’s 2011 solo exhibition “The Shelter: All Fears Come from the Unknown Shimmering at the Edge of the World” consisted of one large-scale installation, over five meters high and made up of 104 paintings joined together and illuminated from the far end of the gallery. Like the dome of a church, the installation openly welcomed the viewers as they approached. Shunning interpretive possibility, only bodily experience was left. Merging on the surface of the installation,

the otherwise “meaningless” paintings granted the work a vague ritualistic feeling. Li seems to be experimenting with creating a new language both solid and spatial in form. She no longer forces meaning on the viewer, yet creates a new barrier to understanding the work by forcing the viewer pay attention to the corporeal sensation.

In Li Shuirui’s latest exhibition “Modadology,” this way of thinking is even more apparent. We cannot derive any meaning from the title or from a discussion of the show’s themes, and certainly we cannot find any meaning in the works. Included are three 2008 works from the “Lights” series, created for an exhibition that was never realized. Originally intended to be hung on the wall, instead they are suspended in the air as a triptych installation. In front of these is a work titled Fragile Yellow. Although the impression is not noticeably stronger than “The Shelter: All Fears Come from the Unknown Shimmering at the Edge of the World,” the artist’s control of space is. Displayed in another room is Sharp, a group of 57 metal sculptures of various shapes are scattered on a floor coated in white paint. The gray geometrical forms, and the bright color sprayed round the edges—particularly sharp against the metal—are an even braver experiment. The artist has cast aside the light she had been studying for so long, leaving only these pretty fragments on the ground. Li Shurui’s way of working and thinking is rigorous. She recognizes the prevalence and limitations of realist methodologies in Chinese art; over the past ten years she has systematically transformed her study of light into the study of spatial perception. Of course, she also understands the danger of a young Chinese artist steering too close to minimalism. Perhaps it is this very concern that will form the core of her practice in the future.