A COLLECTIVE OF INDIVIDUALS

| August 2, 2010 | Post In LEAP 4

Simon Kirby had just called in a food delivery. Kirby, director of the gallery Chambers Fine Art Beijing, was sitting in the Ai Weiwei-designed gallery courtyard out in Caochangdi on a summer afternoon, plotting an exhibition with his visitors. He asked Yangzi about the origins of their group, the Wangjing Painting Society (WPS). Then Dong Xing, a Goldsmiths graduate, started in on the substance of the proposal. Slowly the conversation shifted from Chinese to English. The proposal he had put together the night before was bilingual. They had brought an idea with them, not a portfolio. “Sounds like a good idea, but how are you going to realize it?” asked Kirby. “What works are you going to show?” Kirby was most concerned with the details of the exhibition, set for the end of July. It was already early June, and time was running short. He wasn’t hoping for a show of entirely new works, nor was he expecting a proposal as complicated as the one before him. The summer gallery show is a blank to be filled in, a chance to do something different.

For galleries around the world, a “lively” exhibition of works by “young artists” had emerged as a popular option. The gallery didn’t know much about the WPS per se, and it certainly wasn’t hoping for a breakthrough with this show. Like many, the gallery knew the group—named for the northeastern Beijing neighborhood home to the Central Academy of Fine Arts where its members frequently convene—through stories and rumors. The WPS, in turn, was looking to do a real exhibition, not just to hang its paintings on serious gallery walls. This opportunity availed itself just as some of the Society’s “members” were starting to ask questions about the group’s direction. Dong Xing and Yangzi, in fact, hadn’t spoken for nearly a year before this opportunity suddenly arose. Yuan Yuan, a pudgy Beijing native and recent CAFA graduate who shows with Chambers and is friendly with the WPS, brought the two parties together.

Yangzi is older than the people around her, nearly 40. To say people are actively attracted to her would be less accurate than saying she exerts a kind of gravitational pull. Perhaps it comes from her distinct personality, or from her interest and appreciation of different creative styles. In any case, at different points over the last few years, in different ways and at different distances, people a decade or two her junior have appeared in her orbit, and stuck there. On a first meeting she comes off as special, even strange. Her appearance, diction, and lifestyle all hint at someone detached from her own generation. She comes off as girlishly innocent and excitable. In her presence, little things seem momentous. She isn’t the leader of the WPS, but she is the nexus. And her living room is its base of operations.

THE WANGJING PAINTING SOCIETY

Yuan Yi hasn’t known Yangzi for very long, but has been living in her home for a month now. She was very quickly drawn in to the group’s discussions, and the first exhibition proposal was actually her idea: to make art based on a poem by Yangzi’s boyfriend, Jiang Jun. Jiang is a quiet computer engineer, his poetry read only a few friends and acquaintances. The idea of basing the exhibition on one of his poems was really a way of looking at how people meet and come together, and for the WPS that meant a return to its beginnings.

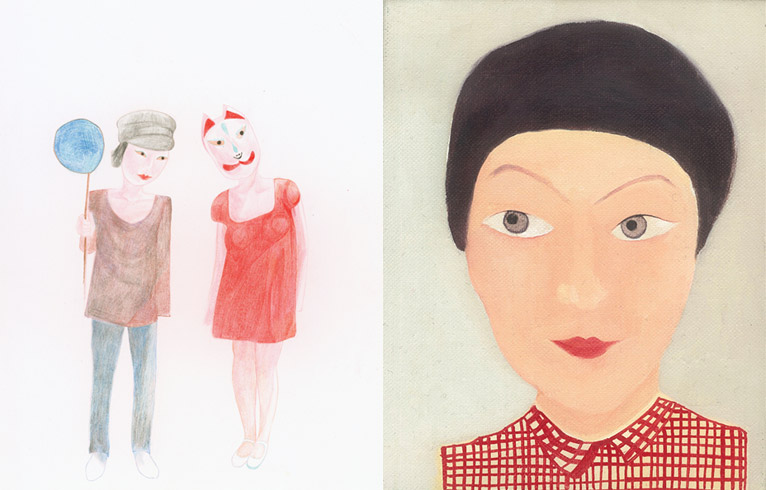

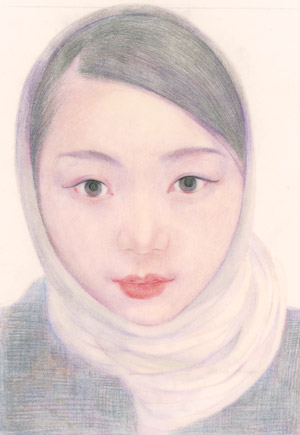

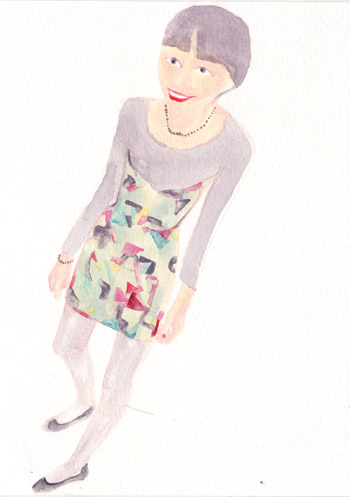

The Wangjing Painting Society was “founded” with an exhibition in 2007 in which Yangzi, Dong Xing, and Jiang Jun all participated. It was held in Yangzi’s home. Dong Xing liked the photos Yangzi had been posting on her blog of children at the Swedish elementary school where she worked as an art teacher. They later made contact offline. Neither Yangzi nor Jiang Jun had any experience as artists at that time. They were true amateurs, and Dong Xing had just finished his undergraduate work at Goldsmiths in London and returned to Beijing. Dong encouraged Yangzi and Jiang to organize a small exhibition against what they phrased at the time as “the systemization of art.” Yangzi started painting in a way that drew on her self-training and hinged on her perceptions. She had found a path that worked for her, making paintings based on photographs of her friends and acquaintances, people closely connected to her life. Yangzi’s shortcomings as a painter are precisely what makes her work interesting. Her backgrounds tend to be monochromatic, and her figures are always standing up, because she doesn’t know how to paint a seated figure. She can’t paint hands either, so she cuts them out of photographs and pastes them onto her compositions. Many believe that these amateurish tactics are what lends her work its special character. Yangzi is not a highly educated woman; her relationship with the world is built on feeling more than reason. She loves to study, but her inquiry is limited by the scope of her world.

The group met for a few days in a row in early June, chatting deep into the night. Most of their time was spent criticizing and correcting each other’s ideas; only much later did they come up with an idea for how to make the exhibition. Along the way, another possible theme emerged: “Revelry,” or perhaps better put, contemplation thereof. The initial idea behind the group was free exchange, and so they began to organize small-scale conversations and lectures, hoping to keep themselves open to different forms of knowledge. This led to frequent meetings and short trips, which in turn made for a small, even exclusive, group. They became a tight-knit unit, intimately familiar with each other. Nonetheless, through the introductions of friends or their own initiative, the group grew larger, and sub-groups began to emerge. Today the impression most outsiders have of the group is one of gatherings and revelry. The “famous” parties in Yangzi’s apartment can be seen in photo albums posted on the social-networking site Douban; the WPS’s Douban group now claims 1200 members, a small fraction of the number who know about the group. And the group’s overall public image is mostly shaped by the photos and texts posted by individual members to their personal Douban homepages, as well as the comments they elicit from others on the site. In the minds of Douban users, the WPS is young, pretty, and fashionable, widely followed and hotly debated. This perception is most clearly manifest in the tone—often light and affectionate—in which the group’s followers leave them messages. The events they organize, like “Re-enacted scenes from Buffalo ’66,” sound “artsy,” and thus are attractive to their young fans. It is as if they exist beyond the confines of everyday life, able to share among themselves a level of taste and a variety of imagination off limits to others. The larger the group gets, the more private and unitary it becomes. In this changed atmosphere, serious attitudes, earnest questions, and mutual inspiration have grown ever more rare.

These two ideas for an exhibition—one based on Jiang Jun’s poem, the other on parties—were not completely opposed, and actually grew out of a similar idea: that the Wangjing Painting Society is in trouble, and needs to change. The group feels it needs to alter its public image, reflect on its internal dynamics, and modify its way of working. If an exhibition based on a poem would be a soft-footed return to the WPS’s early days, the “revelry” exhibition would be a manifesto, a rogue expression of abandonment for the present. Dong Xing’s most extreme proposal called for using one room of the gallery to show works by WPS members, and the other to show works by “established” artists that would critique the idea of art as party.

But Dong Xing couldn’t ensure, even in the course of so many discussions, that the WPS really had produced any works of a “clear attitude and critical stance,” as he so hoped. Would there be enough works that could “stand up” on their own in the context of an exhibition? Or would they be more like “illustrations?” “Illustrational” is the most common critique of Yangzi’s work, as well as that of most other group members. Yet neither did Dong hold out much faith in the works of what he called “the art academy crowd,” even if those people had received formal training. They may be technically proficient, thought Dong, but they “lack a sense of self.” And “sense of self” was a word that came up again and again in their discussions. If hanging out together, being charming and enchanting on Douban was a symptom, then what sort of understanding of “self” or the relationship between self and society did it betray?

INSIDE AND OUTSIDE

“Taking a poem as a motive for an exhibition seems affected, difficult to expand upon, tough to justify in a public context. It is a starting point rather than a core,” Dong Xing wrote in his exhibition proposal. Dong was clear on the limits of young people’s focus on the “self,” and sought instead to champion a more open, pluralistic way of thinking. Given the group’s limited time and talent, he was wanted this openness to manifest itself, if only in a pluralism of form. And yet despite the energy he was putting into the project, Dong was reluctant to involve himself in it as an “artist.” Like many young artists, he is extremely cautious about when and how his works are shown. The notion of being an artist in the traditional sense, it seemed, loomed larger for Dong than for others in the group.

For Dong Xing, Yuan Yi, and a few others, the question of what the group is was not so important; they were not interested in the idea of a group identity, or of reflecting on its working methods. Rather, they were curious to see what sort of visual expression its conversations might take. For Yangzi, however, the identity of the group was all-important. She had come to feel a sense of responsibility for this loosely defined collective, not to mention a pride in its hipster street cred, and still hoped to spur it toward “progress” through a conscious rebuilding.

A collective of youth, the Wangjing Painting Society has no set leader, no manifesto. Their internal structure is diffuse, subject to change and defined by the differences of its various members. Still maturing, its members constantly change their thinking and positions; truths once firmly recognized may suddenly seem ungrounded. The idea of returning to its beginnings can only be said to be an attitude, and a way of staying in dialogue with the people the group members once were. Some qualities they have always held dear still remain—diligence, vigilance, openness, and a refusal to stagnate. Their mutual recognition is not based on an assessment of the quality of their work. It is instead a feeling, not clearly definable but established through observation and interaction.

Different educational backgrounds are perhaps the group’s most obvious problem. For Yangzi, Dong Xing represents advanced culture, his perspective broader, his ideas smarter, his linguistic abilities more polished than hers. She uses the word “superstition” to describe her belief in Dong. Yuan Yi says he likes him for his theoretical savvy, for the rationality he gained by studying in the West, his intellectual rigor. But he still needs some distance, some time to digest and decide for himself. It’s not as if these others who have not lived outside China don’t know about the world around them, and they do make their attempts to engage with the national situation, not content to be controlled by a vague understanding of information from beyond.

A week after the meeting with Kirby, the exhibition was decided. The Wangjing Painting Society would not get this “opportunity” after all. But the process of preparing it, full of chaos and uncertainty, showed that they all lacked experience, having to resort to imagination and speculation. They only thing they could agree on was the need to make art with added diligence. Perhaps that’s exactly what it means for a young collective to encounter the world beyond it, to shed the limits it so comfortably set for itself. They do not command much in the way of resources, and confronted with the art system and its rules of play, they necessarily fall subject to the suppositions and predictions of the adult world toward youth. They had always been direct about their work, not strategic.

They could not but help but be changed by this first interaction with the world beyond them. It changed them, moderating and sharpening their behavior as they made choices about when to evade, collide, and maneuver. They didn’t get their show, but perhaps, they thought, for the better. Maybe that’s just what it means to be young: in flux, without the guts or time to overturn oneself, and unable to come to immediate conclusions.