FUJIAN: THE BEST EDUCATION

| October 2, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

1

Almost every Fujianese family has a child who has left home to find work. In New York, only the Fujianese mafia competes with the Sicilian. In Europe, Fujianese farmers exploit Westerners’ worship of organic produce, substituting Oolong tea for red wine and selling shoes made in Jinjiang, Putian, and Fuzhou in the process.

In the world of art, Fujianese have their own “dream team.” Quanzhou native Cai Guo-Qiang has set off mushroom clouds on the military testing grounds of Nevada and staged his own exhibition at the Guggenheim; Xiamen native Huang Yong Ping has filled European museums with his Buddhist and Daoist-inspired creations. In Beijing the Fujian Natives Art World Friendship Association is already in its eighth year, organizing a well-known dinner with each passing New Year’s; from its beginnings as a small gathering at which Huang Yong Ping lectured to friends on Chinese history and culture, it has become an organized event with speeches and a program, a veritable annual meeting.

But the Fujian crew does not exist as a shared entity in terms of artistic style. In the art circle, Fujianese who have left home are seen as loners, often described as “a forest of lonely trees” in a metaphor that takes its cue from the province’s characteristic banyans. Of course that’s not to say there are no collaborations: one year at Spring Festival, Putian native Lu Jie went to Zhangzhou to visit Qiu Zhijie, traveling together to a nearby village and eating many a meal along the way. They visited a revolutionary site on the Jiangxi-Fujian border, part of China’s sacred red heritage, and in the process came up with the idea for the original “Long March Project.”

True artists must be lonely heroes. Finding a way out of the fog of the universe, and finding an aesthetic and a method by which to proceed, is a responsibility they must be willing to bear. But what is a hometown? For artists who know best how to prettily preen “on stage,” home is a place to be from, and leaving home is absolute.

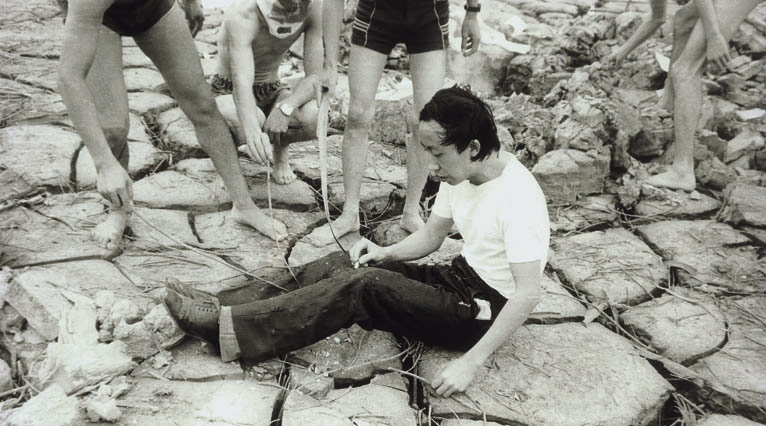

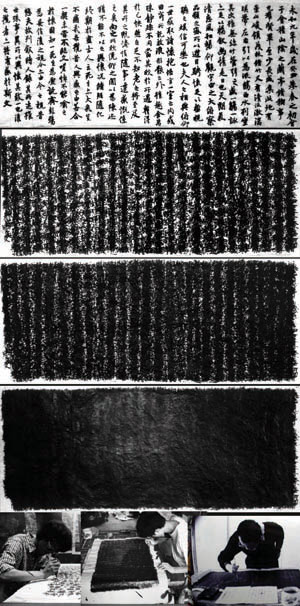

Still there are those who know exactly how to use their background and ties to home. Most artists are reluctant to admit the influence of home and childhood on their works, but Fujian artists are especially gifted at finding material in their backgrounds, or developing a system of their own. When Qiu Zhijie made his breakthrough piece Homework Assignment No. 1: Copying “Orchid Pavilion Preface” 1000 Times, or later wrote calligraphy with a flashlight, he was actually just continuing the studies he began as a child at Nanshan Temple. That sort of familiarity with the written tradition takes a lifetime to develop.

Cai Guo-Qiang openly admits the influence of home on his work: “I always look for things in my own history, developing resources. From Quanzhou, I have taken sailboats, herbal medicine, feng shui, and lanterns. My home is my warehouse.” On feng shui: “I have always believed in the invisible world, I am superstitious.” This is a classically Fujianese outlook. Cai Guo- Qiang likes to borrow on the power of nature. He has a Kwanyin figure in his office, and every time he has to fly, he must first look directly into the airplane to “divine” whether or not it will safely land. He consults with feng shui masters on the locations of key projects, and the work with which he gained widespread acclaim in the American context was titled How’s Your Feng Shui?

National Art Museum of China director (and Fuzhou native) Fan Di’an, while he has never discussed Fujian artists in terms of their shared home, has nonetheless written of Cai: “I have always believed that his hometown of Quanzhou has been useful for his art, particularly on a spiritual level… more precisely, this city has historical roots and cultural structures have been ineffably important in shaping his artistic method.

2

Fujianese culture is like a giant Hakka meal: different elements are stacked atop each other, the flavors interpenetrating. Its historically isolated geography has lent itself well to the preservation of traditional culture, and generations of immigrants have brought to it the culture of the central Chinese plains as well as all manner of foreign religion and folk belief. Meanwhile, its continuous coastline and commercial ports have cultivated its continuous absorption of Western ideas as well as a swashbuckling fisherman/pirate personality.

Traditional culture was once a costume worn by Chinese art on the world stage, but for artists, stopping merely at the use of these symbols was never enough to allow for their own creativity or values; the only real value lies in developing these things in accordance with a contemporary idea and practice. Huang Yong Ping and Cai Guo-Qiang have proven good at incorporating Daoist ideas and working methods into their practices, where Qiu Zhijie, younger by a generation, has shown himself to be quite the Zen practitioner. (Coincidentally, Qiu and Huang are both dedicated students of Western philosophy.) Their works thus share something, perhaps in terms of temporality, chance, or an emphasis on process over results. These special characteristics fulfill this global age’s demands for “world art,” building for the world a special kind of “Asian method” or “Asian aesthetics.”

On an individual level, when traditional and folk culture become personal experience, they can also be digested into creative resources. Painter Wang Guangle is a native of Songxi in northern Fujian. He left home at a young age to study at the Central Academy, and has remained in Beijing since, making abstract paintings, and not particularly feeling any influence of his home on the way he works. Suddenly one day, he began using a brush to swipe acrylic pigments onto canvas layer by layer, and an image suddenly appeared from memory, his grandfather in a room of his house, adding a layer of varnish to his own coffin. This is a custom among old people in this region, to start the preparations for their own death. Year after year, life continues, and the layers of varnish grow outward like rings of a tree. This is a truly Eastern view of life and death: mechanical conduct serves as a protest against death, which becomes a form of confrontation and concern. Thus, fearful waiting becomes patient waiting, and death becomes the next life.

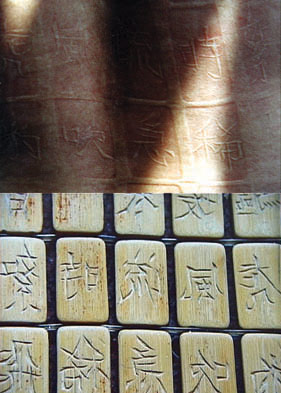

Qiu Qijing, a native of Fuzhou, has chosen another route, finding a critique of the contemporary in traditional Shoushan stone. This stone, called min by the ancients, is softer than jade, and was often used for seal carving. Qiu comes from the same place as this stone, and after graduating from art school, he spent a few months holed up there, quarrying by hand, carving piece upon piece of this old stone into human faces, and then making bases for them, turning them into stone people. At first he made a few dozen, but felt this not enough, so he made a hundred, then a thousand. In the end, there were 2300 of the figures, enough to finally fulfill what for Qiu was an almost biological desire. In the process he used forty tons of stone, and eight tons of metal tubing for the bases.

Qiu Qijing turned these stone people into an installation and performance piece called The Great Migration. The entire process of realizing this work seems almost literary: first, “making people,” albeit in a much tougher and harder way than the Chinese goddess Nüwa who is said to have sculpted people from the dirt. Next is a postmodern version of Dayu driving away the mountains: the works are first exhibited on Shoushan, then elaborately transported away, a migration of the stone people first to Fuzhou, then to Beijing, Shanghai, and elsewhere, using all possible transportation tools: donkey carts, horse carts, tow trucks, flatbed trucks, bicycles, peasants, and freight trucks on superhighways.

The hometown card is a tough one to play; used poorly, it looks lazy and cheap. The artist must make the easy thing look elaborate, distinct, and perceptive through tricks of observation and method, lest he or she slip into cliché or superficiality.

3

Home, aside from implying the site of a collective culture, also implies personal history and feeling, private experience and memory.

ssssssssssssssssssssssssss

ssssssssssssssssssssssssss

When Qiu Zhijie thinks back on his home, he without fail will mention two things: one is the monk in Nanshan temple who spent his life painting plum flowers in the air, the other is a Buddhist sutra in the temple written entirely in human blood. These two stories get Qiu laughing about the whole notion of contemporary art.

Wang Guangle’s requirements of time, process, and purity of technique might be traced back to his childhood home. Next to a river, in his memory the home is dark and black, one room leading to another. The brighter it was outside, the darker it would be inside, with beams of light coming in through cracks between the doorbeams and taking on a definite shape. Only a few years after painting it did Wang realize that a piece which he spent a month working on, the piece for which he won a graduation award, titled A Beam of Light in a Room, had taken shape in his eyes during his childhood.

Qiu Qijing, before he became a contemporary artist, worked in the market for traditional Shoushan stone. He bought his parents a home and supported his older brother’s marriage with money he made selling stone. When he gave up this lucrative business and came to study as an extension student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, he thought of how he would pluck rocks from streams as a child, of the innocent happiness of playing with mud. “I was making sculptures before I could even read,” or so he understands his artistic identity.

4

From another perspective, a home is where an artist builds himself, just as prenatal education can impact a child’s whole life. The advantage for artists from Fujian lies in how, as they confront the external world, their home offers a special way of thinking, a deep font of cultural and personal resources, and an independent spirit with which to go off into the world.