SONG DONG: THE WISDOM OF THE POOR

| July 5, 2011 | Post In LEAP 9

Song Dong first began working on his series of installations entitled “The Wisdom of the Poor” in 2005. One piece from this series, the large-scale installation Song Dong’s Parapavilion, is to be shown at the Venice Biennale this year. Apart from this upcoming show, none of the works from this series have previously been presented to the public, and, until recently, had been lying forgotten in Song’s Beijing studio in Changping. In 2005, Song collaborated with his mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, on the installation Waste Not, which was first exhibited at Art Space Tokyo at 798 in Beijing. The piece consisted of two parts. The first was the wooden frame of a courtyard house. The rest of the exhibition was given over to innumerable everyday possessions— many now old and broken— that Zhao had accumulated over several decades. This “collection” of his mother’s household items validates the old Chinese saying: “a broken house deserves a thousand things.” It exposes an inter-generational ability to, when pressed, subsist on only the most meagre of material possessions, and the resultant philosophy resultant. The readily-apparent nostalgia exudes a sense of the pathological yearning of his mother’s generation for security and loyalty. The latter, particularly, precipitated the creation of “Intelligence of the Poor”.

According to Song Dong’s description, his father’s sudden death— which had to be concealed from his aging grandfather— sank his mother into a depression she found hard to bear. This was where her “collection” began. Not only did she collect things; she left them strewn around the house: “She wanted these things to fill her space, to make up for the absence of my father.” Song’s collaboration with his mother can be regarded as an act of filial piety. The art lies in his helping his mother to exhibit her own life. Old, useless things were imbued with a new purpose. After Song’s mother arranged them, they embodied the principle of “waste not”. At the same time, by reflecting the glory of her lost youth, they released emotions long pent-up. In the end, Song’s mother decided to leave her old belongings to her son, who in turn transformed them into art, letting his mother begin a new chapter in her life.

Waste Not is a deeply moving work of art. Regardless of whether the work is Song Dong’s or his mother’s, the profound affection between a mother and a son intrinsic to the work dissolves the psychological gap separating their two generations. Rather than widening that gap, the reverence shown these “things” turns them into, in the eyes of the viewer, precious objects, opening an emotional dialogue between individuals and objects. As “observers”, spectators can read their own personal experiences into the work, producing an even richer emotional resonance. But Waste Not’s openness, in the context of Song’s artistic practice, is a response to a single, solitary object: life. Song’s has ten year’s experience as a working artist, and the work makes the logic of his art abundantly clear. Song often says that “art is life, life is art,” just the sort of circular reasoning that is clearly evident in Waste Not.

For the individual, life is in the particulars. Since his first well-known piece, Next Class, Do You Want to Play with Me? (1994), Song Dong’s work has always contained autobiographical elements. Next Class drew together installations, video, paintings, and performances, all drawing on his occupation at the time (middle school art teacher). It was his attempt to make learning fun, so as to call the audience’s attention to art in an interactive way. In the 1999 exhibition “Supermarket,” Song Dong dressed up as an employee of the “Song Dong art tourism agency,” giving viewers helpful contemporary art shopping tips. Although in Waste Not the artist appears to have hidden himself behind a discussion of familial relations, the piece is, in fact, art therapy for his mother’s battered spirit. Such a focus is clearly related to his years spent as an art teacher. The three aforementioned pieces mark distinct phases in Song’s development, from which we can identify shifts in his artistic vocabulary: as he became increasingly able to draw strength from his identity as a professional artist, his language gradually became more subtle, the relaxation growing out of the focus that strength created. These changes are echoed in Song’s unceasing expansion of the presence of the experiences of everyday life in his work; as far as the artist is concerned, from their very inception, his ideas will always be mediated through “life.” Thus we arrive at Song’s maxim: “That left undone goes undone in vain; that which is done is done still in vain; that done in vain must still be done.”

This phrase, so imbued with Buddhist philosophy, dovetails neatly with his notion that “art is life, life is art.” It encapsulates the artist’s essential attitudes toward art and humanity. Born in 1966 in Beijing, Song Dong grew up in the hutongs of west Beijing. He witnessed firsthand his parents’ love of life. Although they were of modest means, they made the most of life’s pleasures— his father, for example, was a construction engineer with a passion for cooking; according to Song, his father was able to make a lot from a little, turning something cheap into something precious. He could take a simple cabbage and turn it into a host of different dishes— a rare feat for someone whose generation lived solely upon the fruits of a planned economy. Meanwhile, Song’s mother made toys for her children by hand, once turning the cap of a toothpaste tube into a miniature red lantern. Song was no doubt influenced by his parent’s resourcefulness; he inherited his father’s love of cooking, and, just like his mother, he made toys for his own daughter by hand. However, his parents’ influence expressed itself more strongly as Song’s artistic ability developed. His mother’s steadfast ability to cope with everyday life helped Song develop his powers of speculation and reflection, and arguably led to the formation of his strong aesthetic value system. With increasing maturity, his work has become more assertive, more clearly able to communicate his essential subjectivity. After the year 2000, Song began a new series of performance installations about “eating”, of which perhaps the best example was a 2009 showing of his Waste Not installation at MoMA. At the Pace Gallery in New York, Song unveiled a collection of “meat landscapes,” sharing with his audience aspects of his life experiences and the workings of his psyche.

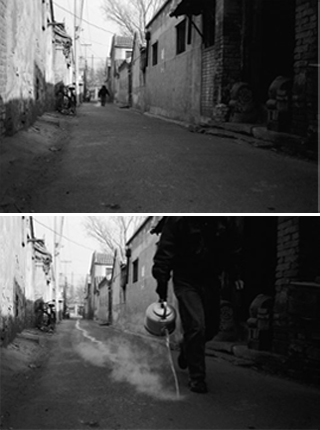

Early in his artistic career, Song Dong created a number of “small” pieces, including his now well-known works Breathing and Stamping the Water (both 1996). A number of other works garnered only limited attention, having barely been exhibited at all— the two aforementioned pieces were perhaps more popular due their symbolic resonance and character being in tune with the concerns of Chinese contemporary art at the time. However, if we re-examine these works according to the artist’s own conceptual trajectory, we discover that they share tendencies with the following works: Reading the Book of No Words (1994-present), Throwing a Stone (1994-2006), A Pot of Boiling Water (1995), Water Diary (1996-present), Eating Drinking Shitting Pissing Sleeping (1999), as well as his international performance piece, Writing Time with Water (1995-2002). It is the emergence of a conscious realization and transformation of an idea of “life” that binds Song’s artistic practice together; like how he preserves each day in his diary, writing with water on stone. Conspicuous yet concealed, remembered yet forgotten, a spiritual state of effortless attainment— here lies the crux “even if you do things in vain, you’ll still have to do them.” In keeping with this tendency, Song also borrowed from a famous Chan Buddhism Koan to name his 2007 sculpture, A Severed Finger. Although, even if, like the young monk in the Koan, Song still couldn’t reach enlightenment after his “finger” had been “severed”, he at least discovered the right path.

In a 2010 group show at the National Art Museum of China entitled “The Dimensions of Architecture,” Song Dong’s video installation Not Grown-Up functioned as a linear re-examination of seventeen years of his video work: it featured his seminal early piece Broken Mirror, as well as Tofu and Kung-fu, made as with Hong Hao, Xiao Yu, Liu Jianhua, and Leng Lin as part of the art group known as the Polit-Sheer-Form Office. Song’s show marked the first public appearance by academics from the Contemporary Art Academy of China at the Chinese National Academy of Arts, and although it was far from comprehensive, it was still regarded as an accurate reflection of Chinese contemporary art; the methods and practices that have gripped Chinese contemporary art since 1989 pervaded the entire exhibition in odd ways. Several of these artists, regardless of their conceptualizations, or their ability to “read” society, long ago began to use these methods and practices as protective layers, nowadays seemingly more centered around calling to attention their own narratives of “history.”

In comparison, Song Dong’s piece Not Grown-Up openly expressed his own concessions— it is in this difference of attitude that the wisdom of Song’s artistic practice can be located, and should also be interpreted as a kind of “Wisdom of the Poor,” just like a pigeon cage built upon the roof of a house, a work which formed part of the eponymous series Wisdom of the Poor: Living with Pigeons (2005-2010). The most important issue is to recognize one’s own limits; this includes Song’s own generation of artists facing up to the “birth defects” of Chinese contemporary art— originating in the imagining of a heterogeneous culture, imitation in spite of misunderstanding. But both the quotidian nature of Song’s practice, and his constant struggle to reach beyond, lend his system a sense of continuity, a far-reaching appeal, a complexity and emotion, or even, perhaps, a faint affection for his nation.