DIGESTING FORMALISM: THE ART OF WANG GUANGLE

| September 19, 2011 | Post In LEAP 10

IN 2000, WANG GUANGLE had just graduated from the oil painting department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. He spent a short time working at a publishing house, and then quit, because he hated the working stiff’s lifestyle, but also because artist and CAFA professor Liu Xiaodong had connected him to a collector who started buying his work, giving him an income of RMB 30,000 a year. Back then, an income stream like that meant everything for an aspiring artist. With a guaranteed stipend, he would never need to work again.

Actually, what left Wang Guangle so confident was not the money, but the fact that his graduation work had won a prize, a feat which surprised him greatly. As he was preparing his graduation show, CAFA’s then-director Jin Shangyi visited his studio and rendered a concise verdict: “No form, no color, no volume,” before promptly walking off. The good student in Wang felt unsettled. Certainly he did not anticipate that he would win the “Director’s Prize” a few months later. A decade on, he can only surmise that “a few of the instructors on the prize committee must have liked me.”

The prize-winning work was a cycle of five paintings depicting the interior of a room, completely empty save for a beam of light falling into the foreground. The cycle was titled Afternoon, in the vernacular of student work. But in fact, Wang Guangle was already grasping at something distinct from the academic mainstream of the time: the honesty of the picture plane. The pedagogy of the 1990s still prized realism and the world of lifelike depiction it implied. Even if educators like Jin Shangyi emphasized “painterly language,” the “language” they called for led an instrumentalized existence, functioning only as a tool of expression. Especially in the undergraduate pedagogy of the oil painting department, the older faculty stressed this instrumental training, esteeming hard technique— accurate color and precise formal mimesis— with little regard for what the students were to do once they had mastered these skills. Or perhaps for them the primacy of realist painting was not up for debate, and the philosophical principles which underlay the realist urge were even more certain truth. Of course, it is also possible that the old guard was not thinking in so much detail. Whatever the case, in the end, it was common belief that a graduation work from the department needed, at the bare minimum, to fulfill standards of form, color, and volume.

Wang Guangle paid little attention to these, having tired early on of the typical oily style of painting, preferring instead to build his painting on the order of the painted plane itself. He might do this by driving his pigments to attain an even, balanced feel, in a process that requires him to use a restrained brush to tap ever so lightly on the surface of the pigment layer, as if taking a rubbing from a tablet. In the same vein, he started to think consciously about how to modify the viewer’s gaze into a surface-level scan, because only in this way can the viewer be saved from an attempt to penetrate the picture plane in a covetous search for “reality.” In other words, Wang had already begun to suspend “reality,” positing that the physicality of the picture plane is the only reality we need perceive. In this sense, we might even claim that Wang took the solid forms and contour lines so prized by Jin Shangyi and transformed them into the solidity of the picture plane and its edges, or that he took the questions before him and answered them by deferring them onto a new realm.

In 2001 he continued his “Afternoon” series, but terrazzo floors began to appear in his backgrounds. Initially used as a background foil for the beams of light that were his real subject, the floors showed an impressive subtlety, ultimately becoming a key subject for him. Worth noting is that even in these early works, there is an inkling of Wang Guangle’s concern with the passage of time, alluded to in things like water stains and light patches on the floors. These paintings depicted a transient moment— the second when afternoon sun hits the floor— and fittingly, painting the sunbeams was a task that could be accomplished in a single afternoon. Painting the floors beneath, however, consumed several weeks. In this way the “reality” of temporal experience is displaced onto the canvas, the transience and permanence of the painted elements finding correlatives in the time and effort actually expended in depicting the two different parts of the painting. In this way, time ceases to be merely an external theme and becomes an internal material, a structural element. Everyone— or everyone who follows recent Chinese painting— knows what happened next, as the terrazzo floors became the only representational object in Wang’s paintings.

In fact, Wang Guangle was not initially so fixated on the “Terrazzo” series; from his graduation works he developed another style of “photo-painting.” In these works he depicted the static of television screens, as the homogenized, controlled brushstrokes and their mechanical nature translated into a feeling of suspended reality. It was in those few years that many other artists began to embark on what they called “photo-painting,” with the hazy finish pioneered by Gerhard Richter becoming a fashion. Very few artists attempted to understand the thinking behind Richter’s painting, with the result that his style was misunderstood and poorly copied, as if it were a variation on realism. Wang’s emphasis on the honesty of the picture plane was enough to support a new take on Richter’s ideas of painting, but compared to the later “Terrazzo” works, these earlier, more representational canvases have not received much attention. In 2003, two exhibitions— Gao Minglu’s “Chinese Maximalism” and Li Xianting’s “Prayer Beads and Brush Strokes” attempted to push the contemporary art circle toward questions of “time,” “repetition,” “abstraction,” and even Zen. This was the moment when Wang gradually devoted his full energies to the “Terrazzo” paintings, abandoning all other strands of creation.

The summer of 2004 was a key period. In this year, Wang Guangle’s studio was earmarked for demolition. Before its destruction, he spent more than a month of long days and sleepless nights painting an entire wall of terrazzo. Against the background of such arduous painterly labor, the temporal valence of the “Terrazzo” paintings finally becomes clear. He worked in the manner of a muralist, erecting a scaffold and painting from top to bottom, left to right, moving along in a structural manner, even though his painting could only be viewed in its details, and never as an overall composition. Portions of the wall completed at different times can be distinguished one from another. Seen from afar, the colors appear alternately to sink and swim. Up close, the brushstrokes float up from the surface of the object they depict, each stroke and its connection with or transition into the surrounding ones taking on a visual existence that the viewer must spend time to apprehend. In fact, Wang never saw this as an exhibition, but as a way to kill time, a long process with no tangible result in store. Indeed, his painted wall might even be seen as a private object, housed inside a flat he had rented for two years, not a public space. Shortly after he completed his mural, the building was knocked down.

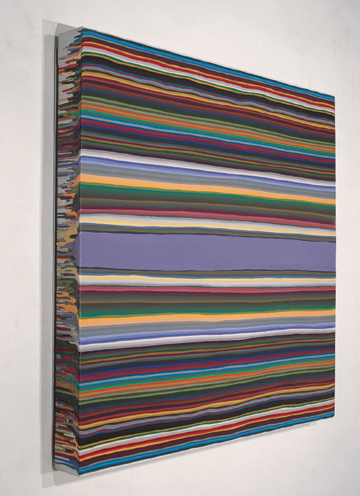

It was in this year that Wang Guangle began the series now known as “Coffin Paint,” adding layers of pigment to canvases according to a predetermined order. One color masked the next, with pigment layers stacking one upon the other. The edges of the canvas wrapped around the stretcher were not spared form this treatment.

Ultimately, time brings about a perceptible spatial change as the center of the picture subtly expands, the way space twists when an object moves through it at the speed of light. Compared with this formal purity, the title “Coffin Paint”— its Chinese title translates literally as “lacquer of longevity”— carries serious sentimental and cultural connotations. It refers to a practice in his native Fujian province, whereby elders will prepare their own caskets, adding a layer of varnish to them with each passing year until they die. I have always believed that Wang is using such a loaded and easily interpreted phrase as a stratagem, a way of winning some intimacy with and power over the viewer for his otherwise non-referential work. The individual titles of the paintings instead reveal a tendency toward purity and seriousness. Named numerically for the day on which they were completed as in 070613, they turn his painting into a stopwatch.

Both the “Terrazzo” and the “Coffin Paint” works, unlike the mainstream of contemporary Chinese art in the 1990s, disavow social or political meaning, emphasizing instead a self-satisfaction on the level of method. Wang Guangle, like many painters who emerged after the year 2000, seems to be both tamping down his formalist foundations (this foundation was initially quite fragile and weak) and at the same time to be opening up a purely aesthetic critique. In fact, it is precisely because of such weak formalist foundations that Chinese contemporary art practice either stops on the level of uncritical realist models, or falls into an unsubstantiated, hollow political discourse of the “avant-garde.” Wang and his peers might be said to be undertaking a digestion of formalism, taking elements that have not been entirely understood and chewing them over for a while. Whether this choice is meaningful gets to the question of whether a formalist approach today carries any weight. And this becomes, in turn, a question which Wang cannot ignore.

Artists during the 1980s and 1990s faced the disintegration of an existing cultural system, but still without the emergence of a new system to take its place. They were thus able to take part in writing the rules of the game. In the decade since his graduation, however, Wang Guangle has worked inside a constantly solidifying art ecology, and particularly, inside a market. Indeed, his career has progressed in stride with the very notion of a system of gallery representation. In this period, contemporary art has gained acceptance from society based on the depoliticized context of the market economy. Wang’s emergence has played out against this background: the constantly developing art market gave him the framework of a gallery system, bringing both convenience and limitations. The gallery system (behind which sits the museum system) provides the artist with set of predetermined ground rules, which first and foremost posit the artwork itself as a consumer good. Whether it is acquisition by a collector or observation by an ordinary viewer, everything is based on pre-planning and expectation, and the artist is hard-pressed to excuse himself from these rules.

Wang Guangle used his exhibition at Beijing Commune in April to express an attitude about all of this. Initially he had proposed to use the method of repeated layering one finds in his “Coffin Paint” series to deal with an entire wall, coating it repeatedly with plaster and paint and ultimately forming a convex shape. Actually, he discovered in the studio— where he previewed this experiment— that he needed a way to further play up the visual effect of this style of painting. Thus, he decided to first install a convex shape on the gallery wall and then to paint on top of that. A feeling of volume became the defining characteristic of the work, whereas temporality became mere ornamentation. Compared with his “terrazzo wall” of 2004, this wall was more concerned with catching eyes. It was more suited to the public display context of a commercial gallery space, but it also severed the necessary and logical connection with his earlier work.

How does one exist in an age of spectacle without becoming part of the same? Particularly, for post-formalist artistic practice, how should one resist the formulaic, or face up to the rapid cycling-through of forms? How should one get beyond the aesthetic standards the art system sets for itself? These are the questions that Wang Guangle and his entire generation of artists are destined to confront.