DING YI: SPECIFIC · ABSTRACTED

| March 14, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

In 1986, a 24-year-old youth did two things. First, he changed his name from Ding Rong to Ding Yi. Second, he drew a grid pattern with the letter X on an 84-square-centimeter canvas and called it Taboo. These two seemingly unrelated things, proceeding from the consciousness of this one person, would put into practice the compression and simplification of meaning, an important turning point in the course of Ding’s art. After studying and being heavily influenced by Cézanne, the artist was attacked on both sides by both Western and Chinese culture, and he felt a complex and indescribable pressure. He was aware that no matter whether in Eastern or Western art, faced with the traditional options of toeing the line or mechanically copying, he was doomed, and that he must “make art more unfamiliar, without the characteristics of painting, without being expressive.”

This mentality, with its anxious, expectant energy, can be glimpsed in Taboo. This painting— the only canvas not part of the “Crosses” series on display here— hangs at the entrance of the art museum’s main exhibition hall. It is this exhibition’s hidden gem, and could also be considered the true starting point of Ding Yi’s artistic career. The painting has a look of both simplicity and gravity, with its expressionist style and notes of the idealism of the 1980s. Demarcated by the crosshatch pattern, the black X’s convey resolution. The sense of ritual the picture plane exudes comes from a kind of handmade informality, and although on the surface it has since been replaced in the subsequent 20-plus years, it has not been diluted. Including 35 works on canvas and 26 works on paper, the exhibition serves as a retrospective of Ding’s work from 1986 until today, and is instructive towards understanding the artist’s “Crosses” series in detail, as well as its influence on abstract painting in China.

In fact, the importance of Ding Yi’s “Crosses” to Chinese abstract painting since the end of the 1980s goes without saying. His simple yet celebrated “+” and “x” motifs are not only easy to identify and recall, but their visual regularity and sense of order mitigate the noisiness and chaos of the age. The manual repetition they necessitate serves to renounce despondence, restoring paintings to their simplest function, dispelling viewers’ hope to see classical construction. After Taboo, then, seeing Ding’s “Crosses” series offers an explanation of the exhibition’s title “Specific · Abstracted,” which is suggestive not of the simplification of material form, nor of purity of spirit. What the degeneration of meaning and the disappearance of the narrative initiate are an even more clear, open-minded method for deduction, and the idea of working with the body: the toil of manual labor, day after day.

Ding Yi once proposed “making painting meaningless.” In an age that emphasizes theoretical knowledge and philosophical enlightenment, with the art world hoisting the banner of cultural critique, unless one works in jest, what is needed is very calm and reasonable insight. This kind of mentality reveals Ding’s wariness of the worship of images and the whirlpool of ideas. With this wariness comes his natural and conscious decision to deviate. Even though Ding’s “+” motifs are the product of the grids used for calibration and coordination in printing, his first “Crosses” painting in 1988 also featured the same standard of lines— against a red, yellow, and blue background, they look like the crosshairs of a gun— his decisions and state of mind were not at all anchored in the mainstream art categories prevalent at the time.

How does Ding Yi identify himself as an artist? This is a prominent question at the moment. During the mid- to late-1980s, many similar young painters in Shanghai inadvertently participated in abstract experimentation, leading to the unique, aesthetically–minded “Shanghai abstract” style. This forms part of Ding’s background. Before painting “Crosses,” he had also done performance art, following China’s modernist art movement of the time. But before he was content to return to the canvas, he used a ruler, tape, and a pen to draw grids and crosses and then color them in. In terms of his painting, Ding has been influenced by Guan Liang, Wu Dayu, Maurice Utrillo, Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Frank Stella and others, the latter two— and this is especially true of Stella’s hard-edge paintings— were of great significance to the formation of the style he used in “Crosses.” In the early “Crosses” period, Ding paid extra attention to eliminating all traces of the man-made and to lending the picture plane a mechanical quality, thereby forming a very terse, neutral, and rational visual language. Through the transformation and development of his works that followed, this style of visual language came to be constantly strengthened.

It is perhaps difficult to attribute the turning point in Ding Yi’s paintings to his caution toward pictorial narration and the interpretation of meaning, or to his evasion of the subjective expression of the surrounding time period and social conditions. There is no simple way to tidily sum up the origins of a certain kind of abstract art. When positioning Ding’s paintings into a specific historical period and into the context of the individual, one may better understand the artist’s incessant doubt and probing, both internal and external, for the balance between absorption and progress; herein lies the gradual maturation of the artist. What this means for Ding Yi is that the regulation and expression of a direct, clear visual sense is priority.

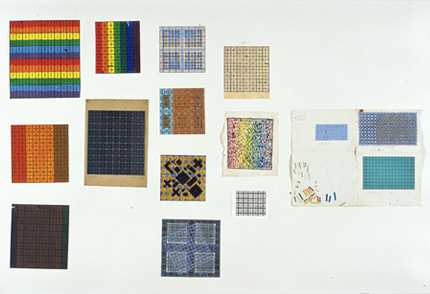

One other notable feature of Ding Yi’s paintings is their display of his enthusiasm for experimentation; this is the essential unifying element of this exhibition. In his 20-plus years of practice, he has tried to use the tools of a variety of mediums. Other than the common canvas, oil paint, and acrylic, he has also used linen, tartan, corrugated paper, fans, charcoal, chalk, ballpoint pen, pastels, pencil, marker, and other materials. The richness of his experimentation can be slowly assessed in a separate space, his paper works and drafts presented on the walls and in display cases. Among these, the long scrolls done on xuan paper using colored pencil and ink, 23 Circles and Cross Sketches, are studies of crosses in ink wash. Bringing to mind the time Ding spent experience studying traditional Chinese painting at the Fine Arts College of Shanghai University, the scrolls also reveal his examination of and rumination on traditional Chinese aesthetics.

From his early “hardened feelings” phase up to the start of his free-hand painting “colloquialization” phase and through his experimentation with different materials to his using florescent lights and metallic colors to depict a hazy Shanghai, Ding Yi’s “Crosses” series has undergone constant change. The diversity and complexity of the underlying implications of the works’ distinct contour— reminiscent of cell reproduction and growth— are closely bound together with Ding’s methods and random color schemata. In this kind of method, each painting has a unique genetic code— the coordinates of each life are different. And the contemporary significance of his paintings is now emerging in the mainstream landscape. The most important part of the exhibition resides in his “Crosses,” which represent more than 20 years of work.

Ding Yi seeks brushwork that allows the brilliance of ordinary colors to flow forth. His utilization of color follows the rules of light, such that it comes to possess an extreme vigor. What is interesting is that Ding is able to simulate natural or urban light with a limited palette: here in eight chalk colors, there in four fluorescent colors, and the black, white, and gray of the four works from this year. These four new paintings are displayed in the back of the exhibition hall in a wide-open square space in non-continuous, muted and plain circulation, seeping into viewers’ eyes previously contaminated by too much color, purifying body and mind. Going from color back to black and white, it may be possible to understand how Ding feels toward the city and life-like flowers blooming before your eyes, there is the nebulous mass of human affairs, and then everything dies down.

From start to finish, Ding Yi constantly pushes the limits. His crosses, his grid patterns, and even the time he spends on these creations are all subject to the limits of the eyes and body. Ding’s last solo exhibition in China was already five years ago. Far from being prolific, his self-discipline and high expectations ultimately slow down his painting speed and increase the difficulty of his work. Some wonder how difficult making his “+” and “x” symbols can really be. In Ding’s paintings, this is not an issue of language, form, or composition and connotation, but one concerning how to give order to a completely chaotic existence— breaking through the restrictions of a constrained environment. From simplicity to complexity and then returning to simplicity, the core is the idea, and not an abstraction. Moreover, this idea is not some insurmountable black hole. Azure Wu (Translated by Caly Moss)