GILBERT & GEORGE: LONDON PICTURES

| July 24, 2012 | Post In LEAP 15

In England, 2012 is a year of celebratory cheer: the sixtieth-year jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II’s reign coincides with the upcoming London Olympics. But in the photo series “London Pictures,” bad boys Gilbert & George lead us through a city that is grim and chaotic, belonging to criminals and the deranged. Gray and beige have replaced the pair’s usual penchant for bright colors. The pristine white walls and glass cases of the gallery add a layer of seriousness to the scene, creating a space full of resistance that enhances the rebellious attitude of the artists.

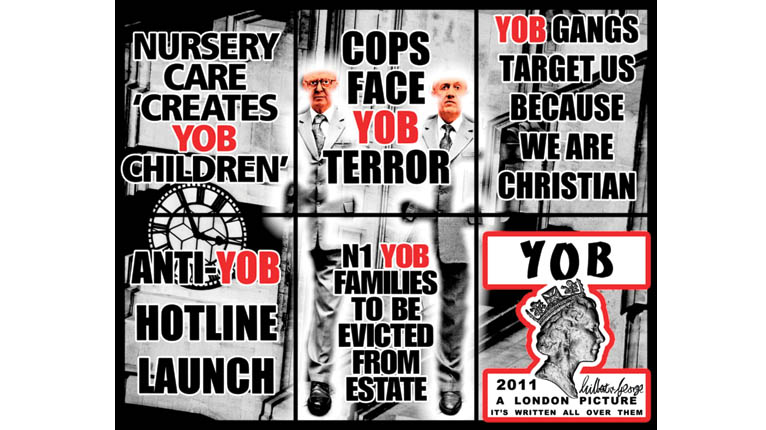

As in the pair’s most distinctive work, the artwork in this exhibition is fabricated using the gleaming glass and iron grid that are typical of contemporary urban architecture. But this time, the walls are covered in newspaper leaflets. The words from these front page headlines come from cheap tabloids meant to solicit as many customers, but today collected together these leaflets instead become a dictionary of London’s violence: burglar, beaten to death, rape, murder, cannibal, mugging… Imposed behind the words are photographs taken around London of dimly-lit street scenes. Occasionally a lace curtain obscures the scenes in the background. (Aren’t lace curtains the veils that hide the bourgeoisie’s embarrassing interiors?) Gilbert & George also make appearances in the pictures, though pasted on the wall they look more like ghosts, their dark shadows reflected in the cold glass. Their defiant faces stare expressionlessly into the distance. Their eyes are empty and indifferent. Like a pair of spirits condemned to haunt the streets of London, they bear witness to the violence and crimes enacted in the name of capitalism for hundreds of years.

Gilbert & George are after more than just image juxtaposition and moral criticism. The verbal and imagery layer together to create room for thoughts and reactions at once sharp and laughable. Each large-scale picture is signed by the artists using currency bearing the Queen’s portrait, though the eras and design vary. This move evokes the customary souvenirs that are produced and sold during momentous occasions, such as a jubilee or an international sporting event. At the same time, it also seems to point to Great Britain’s display of glory as a ridiculous attempt at reliving a long-lost colonial past.

Even more interesting is the wordplay that Gilbert & George deploy around the meaning of “straight” in the titles of several pictures. On the surface, the use of “straight” is meant to distinguish the typeface in the original newspaper flyers. The underlying meaning, however, creates a relationship between the typeface and the colloquial usage of “straight” to describe non-homosexuality, or heterosexuality. Here the artists are pointing attention to the unnecessary distinction made when referring to homosexuals in a supposedly open society.

Tirelessly using fragmentary images to evoke the big city, Gilbert & George have made London the center of the universe, or more specifically, they have made it their home base at Liverpool Street Station. Theirs is a London that has been decomposing since the days of Dickens, when the poor souls who wandered into the city were “as a drop of water in the sea, or as a grain of sea-sand on the shore…. Food for the hospitals, the churchyards, the prisons, the river, fever, madness, vice, and death,—they passed on to the monster, roaring in the distance, and were lost.” (Charles Dickens, Dombey And Son, 1848) At the center of the universe is a black hole that swallows everything that comes its way, and this is the world that “London Pictures” reveals to us. Aimee Lin (Translated by JiaJing Liu)