TAIWAN’S LISTENING STORIES BY YANNICK DAUBY

| November 9, 2012 | Post In LEAP 16

Born in France in 1974, the sound artist Yannick Dauby initially began his research and creative work in music, which have substantially expanded into improvisation, electro-acoustic composition, and ethnomusicology. He continues to engage with natural, urban, and industrial environments in an on-going series of sound recordings that find their way into his music arrangements, CD releases, and various other forms of output, such as multimedia performances, recordings, improvisation, and sound installations. Occasionally, as in the case of his experimental collective work, these are also available on the Internet for streaming and download. At the core of Dauby’s work are experiments with the aural experience, as well as collaborations with sound artists, musicians, plastic artists, and dancers. In recent years, he has been living and making field recordings all around Taiwan. Major recent work includes the albums Taî-pak thia sa piàn (2011), Sounds of Horse – Music for Dance (2011), and the exhibitions “Revitalization of Chiayi Sound Project” and “Wa Jiè Méng Xun.”

STORY ONE: TATAMI MAT

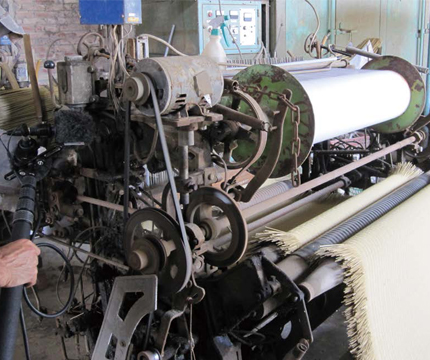

I was inside a workshop, in front of a half-broken machine, of which we were hoping to preserve some audio traces.

All of a sudden, I forgot the reason that bought us here, stopped thinking about the unique character of the place, ignored the machine’s actual function and temporarily dismissed the wonderful people who made my unforgettable day. As if the only thing that existed were the elaborate, vibrating sounds of the machine.

The two microphones on my boom were approximately 15 centimeters apart. As I came closer, only a few centimeters away, the muffled snorts and shrill chirpings of the machine became formidable, but lost the magnitude and certain details when I took a few steps away. This made me aware of the complex formation of and interplay between the sounds: crisp, rapid strikes accompanied by low, rhythmic pulses. With the slightest turn of hand— really, even minutely— all the sounds, amplified by the headphones, suddenly swung from one ear to the other. Moving my boom around to peruse the entire machine— including, nearly, its interior— I found at each location a very unique sound situation

In reality, I was not listening to sounds that came directly from the machine, but a series of electrical currents translated by the microphones and transmitted through headphones, which sat tight on my ears, with little air in between to cushion any possible aural shocks. I heard only the trembling of the diaphragms. Or rather, the three sets of eardrums— the microphones, the headphones, and my ears— were all vibrating together. I concentrated solely on the patterns, energy, progression, organization, formation, and color of the sounds.

Using electronic devices as a medium, the above processes were a practice of “reduced listening” (écoute réduite; a term coined by Pierre Schaeffer and Michel Chion) between the object (the machine) and the subject (me).

Let us return to the context in which these sounds existed. Summer, 2009. A small village in Chiayi County in southern Taiwan. A tatami-weaving machine made in Japan some 80 years ago. The shabby workshop was the last of its sort in the village. Soft rush, the type of straw used for weaving, was cultivated and harvested a decade ago when the region’s climate was still suitable for the plant. The workshop owner worked only one hour a day, so that the fairly large supply his father had stocked back in the days could last a bit longer. Today’s village had lost half of its population and become quite peaceful, although the sonorous rhythm of tatami looms that had swayed throughout the small town day and night since the Japanese Occupation only came to an end in recent years.

Such narratives are indeed essential in recontexualizing my recordings. But in the recordings I only strived for the utmost musicality, that which was capable of conveying the machine’s formidable momentum and the incredible myriad of sounds it produced.

Listening to the recordings again in my studio, I realize that the complexity of these organisms of sound is manifest through certain bodily effects. The loudspeakers vibrate the way my microphones did as they faced the weaving machine in motion, reminding me of the variations of my gestures as well as the cooperative interaction between the body and the mechanics of sound. The image is absent, and for the better: given the lack of a visual aid (even if just for a second), we must plunge ourselves into the purely auditory to perceive a scenario. Each moment, confronted with the stereo field, we are alert and attentive, detecting, and diagnosing every approaching sound— a listening that explores the sound’s transient structures as it jumps from one detail to another. Our mind reads the recordings the way a conductor reads the score of a multi-part symphony. We measure every vibrating molecule in the air.

STORY TWO: TOBACCO LEAF

In 2006, I created a folder on my laptop that contained recordings in chronological order. It was also that year that I bought a hard-disk recorder. Before then, my archive of digital files and cassettes had been a complete mess, and I had to excavate from large piles of recordings to find anything prior to 2006. More often than not, my thoughts would oscillate between the excitement of discovering some long-forgotten material and the unsettling discrepancy between archive and memory— something I call “Listening Capacity Repository.” Up to this point, I have never let others touch them.

In the repository is a series completed this winter that I deem satisfactory, meaning that I will eventually sit down and edit them, condensing a whole day’s recording into a few meaningful minutes. Perhaps this work of phonography will be shared, passed on, and experienced by others in different ways. The outdoor recording begins with old ladies chattering in Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka— both languages that I cannot understand— while short clattering sounds permeate the stereo field. From the recurring noises, one may discern the sound of farming, an amalgam of the sounds of manual labor, a truck, and a few birdcalls…

No explanation, let alone narrative. Only the sense of speed of these bizarre sounds coming out intermittently from the loudspeakers. This is not a medium that best illustrates and records the activity. We listen, haphazardly, somewhat attracted, trying to concentrate, but still have no clear picture of what has happened. Later, a new sound catches our attention: clusters of steady “pata-pata” sounds. Then a similar voice, this time in a half-open space. Such details are reminiscent of the soft echoes heard in a countryside setting where there are walls within close range.

Suddenly the landscape changes— sounds of heavy breathing, men cheering, crisp clicking sounds and rubbing noises are heard in a much closer range. The open space from seconds ago is replaced by many auditory details that enforce a sense of closeness and claustrophobia. We then return to the previous field, where the “pata-pata” sounds again. When I listen to this recording, I have no clear visualization of what my aural perception has captured. It is rather my body that experiences the alteration of space.

Rather than delivering words, the human voice becomes an existence in flux, dispersed all over the place so as to trigger other mechanical sounds. My footsteps on the farmland provide no information about the quality of the shoe sole or the geography of the country, but rather a sense of the sounds’ manifold textures. Instead of recreating and reenacting the situation or setting, this morphology of sounds tells a different kind of story.

On this late-winter day in southern Taiwan, I recorded the tobacco harvest and the processes of curing. Years ago, at the end of an educational music event in Meinong, a local friend suggested that I record the sound of the tobacco harvest— the sound of leaves being ripped from the stem. “Record it before it disappears from this place forever,” he said.

This, of course, was not the only sound—there were also the tobacco farmers who had created the area’s famous jiaogong, or “labor exchange,” a communal network that allows them to assist one another. The acts of cultivating and harvesting tobacco takes place at a time when, after an entire year of rice farming, people are able to come together again and work on the winter field. My recording did not tell of the vicissitudes of global economy or the socio-economic metamorphosis (if not demise) of the place. For that, it would have to be supplemented by descriptive images, language, and words.

I am actually more familiar with the sounds of animals, which possess an inherent performativity. For example, the chorus of frogs features an almost geometric precision; the collective flow of sounds, composed of countless tiny units, resembles that of a river or a light breeze in a bamboo forest. Yet in this scenario— witnessing a distinct labor in the winter of 2012 in the Taiwanese countryside— I had to be a pro tem radio journalist, a sound anthropologist, or an independent sound maestro (as if directing on a movie set). The role allowed me to listen closely to the “voice of human beings.” Rather than recording the sound of the plant, I spent the entire afternoon following the lives of the farmers at a half-meter distance, trying not to step on them between rows of tobacco plants.

I didn’t intend to interfere in their work, but my exotic looks stood out immediately. We would share a smile at these peculiar encounters— not the kind you feign at visitors, but a smile brimming with genuine humor (the astonished look of the recorder further attested to this). Daily clothes functioned as diving gear for the old ladies, protecting them from the sun, dust, and the plant’s sticky sap.

The recording device gave me a reason to stay near them, and the boom seemed to have triggered a dance: I positioned myself in a corner, waiting for the men carrying batches of tobacco leaves into the curing room. They would sometimes wait for me, winking, with slightly exaggerated gestures. The constant movement of the microphone successfully captured the scenario, where different people were making sounds at the same time. In fact, no one present at the time could have had a similar experience, mine having been significantly magnified, furnished with a greater depth of field and other measures of strengthening sensory perception. The act of listening pressed me to assume a unique bodily position, allowing me to come into contact and interact with those who were prepared.