Unbroken Sounds of the Times

| February 20, 2016

In the 1960s, German contemporary music master Karlheinz Stockhausen noted that “the distinction between sound and music disappears.” Perhaps we can open up a discussion of the subtle relationship between sound art and the plastic arts. For a long time, their differences have flaked away through level after level of conceptual framing. But the gap still has not disappeared completely. Sound art is still a relatively fresh testing ground for experimentation. Sound is like an active tectonic plate, splitting in the earth to bring forth the sound of the future.

Lebanese artist Tarek Atoui, in his Infinite Times Zero (2011), seemed to want to conduct the entire social sound landscape. All the way from Beirut, Lebanon, to Damascus, Syria, he completed a continuous, unbroken string of performances across numerous locations over the course of eight months. His source sounds were not from the natural world but originated in sine waves and methods of restructuring or reducing simulations of the sounds of a city. Through a computerized device he designed, the end of each performance automatically triggered a link to the next performance at another site, where his next installation awaited. The progressive domino effect of this series created a sound experiment focused on the concept of a symphony of city sounds: an attempt to translate each region through the complexity of its sound profile.

For this piece, the artist acted as an on-site performer, a musician. In Pierre Schaeffer’s mid-century musique concrète, sound is redeveloped and expanded using the methodologies of composition. In the piece Helicopter String Quartet, Stockhausen conducted four string players in helicopters, their performances simultaneously mixed by audio technicians in the performance venue. This was, in fact, a behavioral experiment of contemporary classical music dipping into sound art. John Cage’s 4’33” confirmed the immaterial possibilities of sound outside performance. Marcel Duchamp’s A bruit secret, a noise-making object hidden inside a ball of twine, is a readymade that increases the invisibility of the shape of sound. More recently, artists like Christian Marclay have evolved dual identities, giving birth to what has become the central issue of research and exploration for contemporary music around the globe: the interaction between sound machines and human beings.

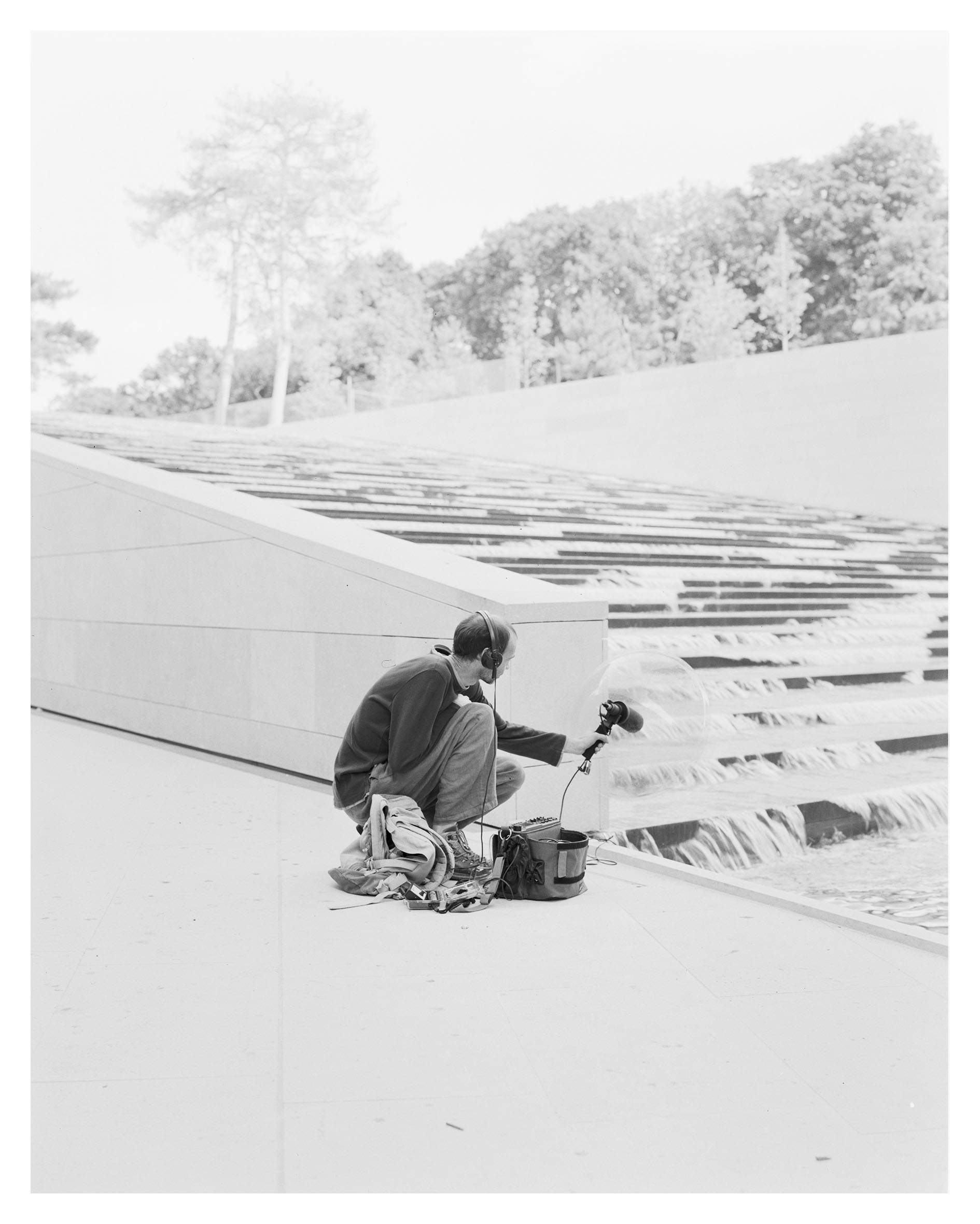

In 2012, the Museum of Modern Art in Kuwait City invited Tarek Atoui to consider the state of confusion in everyday experience. Unplified positioned a small, light-filled cabin in the museum courtyard. The structure was separated into two connecting rooms with no air conditioning. One played a desert soundscape with real-time audio produced from a custom feedback system. The second had four microphones, which the artist used to amplify the audience’s movement through the space—natural sounds of the environment drowned out by the audience, or vice versa.

In the wind-eroded landforms of the desert, this work finds not oil but the hidden past of Mesopotamian civilization. This piece is both an experience of the environment and an allusion to the political and economic course of history. By reminding us of the political culture covered by this topography of sound, Atoui hopes to reveal the migration between two states of being and identification: the source of civilization located somewhere in history, and human society as it exists now. These two states merge into a three-dimensional terrain that resonates with our abstract, confused consciousness, reflecting the anxiety of the Arab world at this moment in human history.

Only with the dawn of the age of the internet have nature, people, and intelligent machines begun to work as integrated entities. Since then, new media have begun to change the ways people connect, and the noise of friction between individuals and society has produced a sonic field of widespread public participation. More so than generations before us, we hear unsolicited soundscapes everywhere. There is a panoramic violence to this intervention in our lives, leaving us unable to opt out. Today’s media has become a complex sound production machine. Out of the rapidly changing patterns of the world—political culture, digital technology, the relationships between humans and machines, individual expression and collective action, humans and architectural spaces—a complex resonance is produced.

All people make sound; they also listen. The condensed landscape of the social performance of Unplified was housed in an art museum, an isolated space within public society. Though the art museum is a common venue for the exhibition of sound art, it is also almost always one of the quietest spaces in a noisy city. Museums are still looking for an effective method of exhibiting sound art. Exhibitions like “Unmonumental,” at the New Museum, in 2008, and “Soundings: A Contemporary Score,” at MOMA, in 2013, are proof enough that, as contemporary art’s “other,” sound art still needs to open up its subject matter—and that it finds itself more difficult to define than ever.

This calls to mind Allora & Calzadilla’s Raptor’s Rapture, which uses sound to travel through the history of human civilization. A musician plays the world’s most ancient musical instrument: a piccolo manufactured from a vulture’s bone that was used by humans 35,000 years ago. A living vulture is the musician’s only live audience. The vulture will never understand what he is listening to, just as we have difficulty truly hearing the endless, unbroken sounds of the times we live in. (Translated by Kantie Pinke)