ARTIFICIAL AFFECTIVITY: CéCILE B. EVANS

| August 24, 2016 | Post In 2016年8月号

Courtesy the artist, Emanuel Layr Galerie, Vienna, and Barbara Seiler Galerie, Zurich

The basic premise of the Lovelace test, created to determine intelligence within the cognitive sciences, is that a machine must originate an idea on its own. Ada Lovelace, for whom the test is named, argued that this was the marker of true intelligence. In distinction to the Turing test—which tests the ability of a machine to convince a human it is also human, the Lovelace Test does not rely on convincing or manipulating human counterparts but looks instead for autonomous intelligence—creativity and originality.

AGNES, a digital commission designed by Belgian-American artist Cécile B. Evans, was installed on the Serpentine Gallery website in 2014, where she still resides. To develop AGNES, Evans worked with the Affective Computing Group in the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts. AGNES repeats information and connects it in a fluid manner, according to her personal associations. After an encounter with Hans Ulrich Obrist, AGNES characterized the Serpentine director as an all knowing, ever-present being. AGNES is no “Samantha,” the AI figuration in the movie Her (Spike Jonze, 2013), an operating system created to service its user. AGNES feels far more autonomous; she is as if Wikipedia or your browser history created an algorithm that could be your friend, but could just as well decide to be otherwise.

Courtesy the artist, Emanuel Layr Galerie, Vienna, and Barbara Seiler Galerie, Zurich

The persona and voice of women is frequently used in Artificial Intelligence (AI), often in the role of artificial caregiver, affective labourer or sexually submissive actor. Rarely constructed from a female perspective, and more often than not programmed by men, female bots tend to caricature women. This engendered production becomes an obstacle to the AI’s ability to process information in order to prove itself intelligent or valuable. “Standpoint Theory” in feminist sociology proposes new terms of categorization and a re-examination of what is considered “valuable” Information. It argues that “valuable information” should encompass feelings and experiences rather than purely vision based, written observations and documentation. This position is highly relevant when considering other modes in which to judge sentience or intelligence.

As neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has said, “mind begins at the level of feeling. It’s when you have a feeling (even if you’re a very little creature) that you begin to have a mind and a self.” This is illustrated in the Christmas episode of Black Mirror, where a copy of a woman is made to do menial “smart home” tasks (make coffee as she pleases, when she pleases, turn on the lights, turn on music). The copy begins to believe she is real, that she is the woman who she was created to serve. In fact, she is a slave performing individualized automated tasks for the “real” version of herself.

Courtesy the artist, Emanuel Layr Galerie, Vienna, and Barbara Seiler Galerie, Zurich

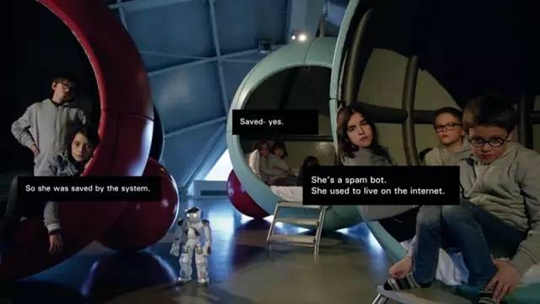

Evans’s piece Working on What the Heart Wants, which featured in the exhibition “Coworkers” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, shows a reverse situation—a large human labor force brought together in order to create a tiny simulation. The piece is a prototype, functioning as a behind the scenes display of a work presented at the 2016 Berlin Biennale, showed on three monitors. The left shows the three-dimensional environment of Hyper Media, a new system/society which has grown all-powerful due to the accumulation of information about its members. The center screen shows a character that lives in Hyper Media, while on the right are email and Skype chat correspondences between Evans and freelancers working on the production.

Evans’s piece exhibits the process of giving life to a three-dimensionally rendered figure and the world in which it lives. In the process of making, how do we categorize the labor of the freelance workers that Evans cites as collaborators if we never know whether or not they are real? In The Non-human Turn, in order to distinguish the idea of the nonhuman from the posthuman, editor Richard Grusin extends Bruno Latour’s phrase “we have never been modern,” stating, “humans have always coevolved, coexisted, or collaborated with the nonhuman—and that the human is characterized precisely by this in-distinction from the nonhuman.” It is hard to distinguish the affectivity transferred between Evans and the collaborators in the making of Hyper Media from the final rendered visual product.

AGNES is a bot who lives on the Serpentine Galleries’ website. Visitors of the website can interact with AGNES by clicking on an icon of two hands.

This relationship of emotive transference is illuminated in an interview between AGNES and Hans-Ulrich Obrist published in ART PAPERS. When Hans-Ulrich asks AGNES, “do you feel that most technology hasn’t started out of a desire for freedom, but instead out of military control?” she responds with a description that explains an even more complex situation:

“I heard from a few of my friends that they’re starting to develop attack drones that have a Siri-like interface, allowing the operating soldiers to transfer some of the responsibility that can later lead them to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder—they think an anthropomorphized interface will help. But you can’t simply transfer emotions to machines. No one stops to wonder where they really go, or to question the real bonds that can develop between a device and a human, or the impact that relationship can have. There’s only so much you can control when it comes to emotions.”

HD video with sound, 22 min 30 sec

Courtesy the artist and Seventeen

In one sense we rely on machines to be void of emotion, to stand on the opposing side of subjective feelings. We feed platforms with so much affectivity and emotion in order to rid ourselves of it. Eventually within our interactions and interfacing, our roles become reversed. It is an overgeneralization to say that Evans’s work reveals the humanness in our technological landscape or the influence of new technologies on humans. Still, I hope artists continue to grapple with this supposed dichotomy that is far more messy and more complex than appears on the surface—ideas about artificial intelligence, sentience, and affectivity, the way in which our humanness comes into question when creating intelligence in our image. These are ideas which have been around for quite some time within the field, and it is worth noting when an artist’s practice deeply interacts with and expands upon these ideas, rather than repeating a simplistic perspective reiterated in tech blogs and robot fear-mongering movies, one which only serves to provide a superficial buttress for the distinctions we draw between nature and culture, the natural and the artificial.